THREAD: Jesus’ Two Genealogies

Why two?

Why genealogies at all?

And what if we don’t know the answers?

For a few thoughts on the matter, please scroll down.

#GodIsInTheDetails

Why two?

Why genealogies at all?

And what if we don’t know the answers?

For a few thoughts on the matter, please scroll down.

#GodIsInTheDetails

Bart Ehrman says genealogies aren’t among most people’s favourite passages in Scripture.

He’s probably right (though there’s time for that to change: Eph. 4.11ff.).

He’s probably right (though there’s time for that to change: Eph. 4.11ff.).

Ehrman also says Matthew and Luke’s genealogies can’t be reconciled. They’re simply different, and we have to live with that.

To an extent, he’s right again. They *are* different, and we *do* have to live with that.

But are they really irreconcilable?

Not to my mind.

Below, I’ll try to show *one* of the ways in which some of the differences in Jesus’ genealogies can be reconciled.

But are they really irreconcilable?

Not to my mind.

Below, I’ll try to show *one* of the ways in which some of the differences in Jesus’ genealogies can be reconciled.

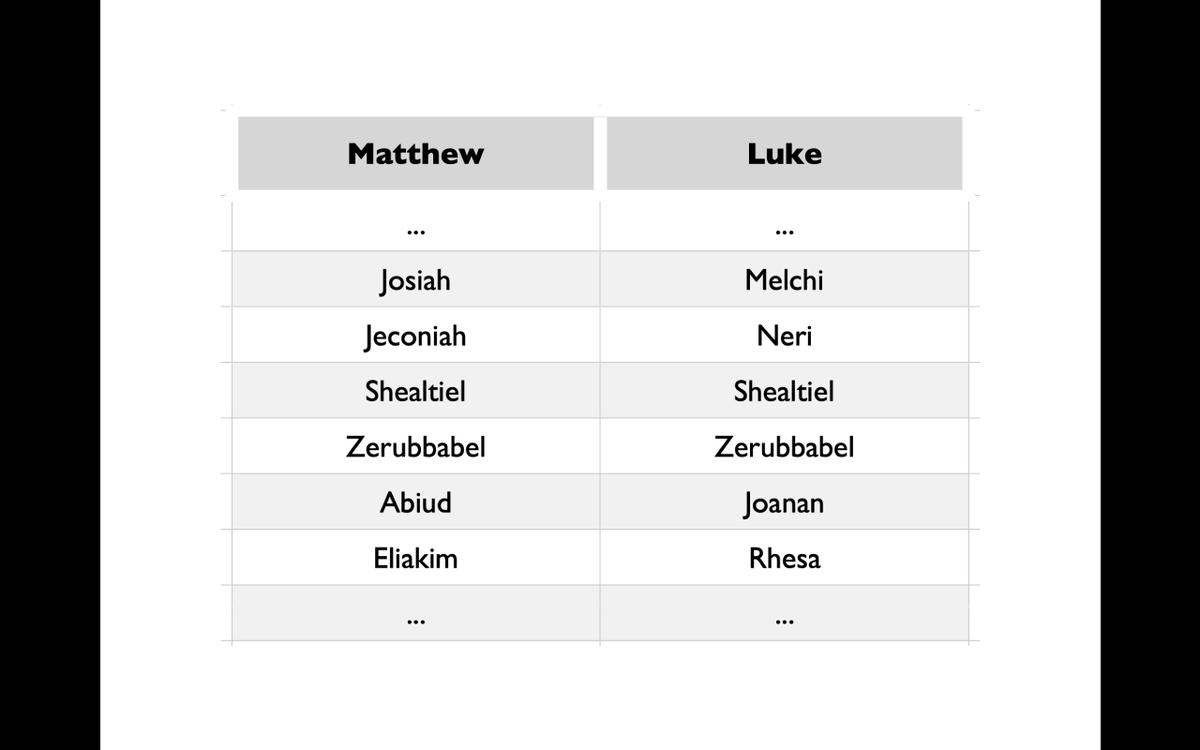

First of all, let’s make sure we’re clear on the nature of the problem.

Matthew and Luke both trace Jesus’ ancestry back to David and ultimately Abraham.

Matthew starts from Abraham and works his way down to Jesus.

Matthew starts from Abraham and works his way down to Jesus.

Matthan and Matthat could plausibly be different names for the same person,

in which case we could suppose the same is true of Jacob and Heli. (It’s not uncommon for Biblical characters to be known by multiple names.)

in which case we could suppose the same is true of Jacob and Heli. (It’s not uncommon for Biblical characters to be known by multiple names.)

But we can’t extend such logic indefinitely.

It’s a bridge too far to also say Achim is another name for Jannai, and Eliud for Melchi, and Eleazar for Levi, and so on.

What, then, to do?

It’s a bridge too far to also say Achim is another name for Jannai, and Eliud for Melchi, and Eleazar for Levi, and so on.

What, then, to do?

Well, before we go any further, we need to notice a significant point of contact between Matthew and Luke’s genealogies.

Matthew and Luke don’t trace Jesus’ genealogy from Matthan-aka-Matthat back to David via *completely* different routes;

Matthew and Luke don’t trace Jesus’ genealogy from Matthan-aka-Matthat back to David via *completely* different routes;

they also share a point of contact at the time of the exile.

Both Matthew and Luke tell us Matthan-aka-Matthat is the son of an individual named Zerubbabel, who is the son of Shealtiel. (After that, Matthew ascends the line of the kings, while Luke takes a back route.)

Both Matthew and Luke tell us Matthan-aka-Matthat is the son of an individual named Zerubbabel, who is the son of Shealtiel. (After that, Matthew ascends the line of the kings, while Luke takes a back route.)

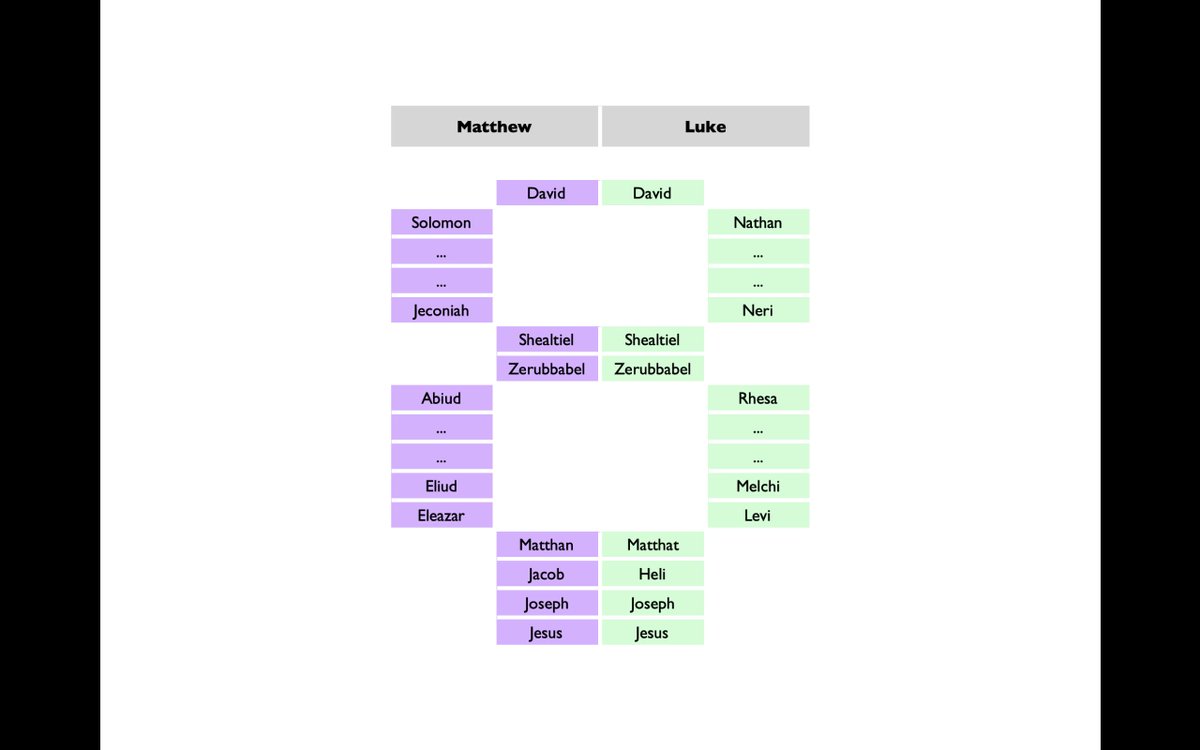

We can thus conceive of the relationship between Matthew and Luke as shown below.

Matthew’s genealogy is purple (the line of the kings: David, Solomon, Rehoboam, etc.),

while Luke’s is green(ish) (an offshoot from the stump of David: Isa. 11.1, 53.2).

Matthew’s genealogy is purple (the line of the kings: David, Solomon, Rehoboam, etc.),

while Luke’s is green(ish) (an offshoot from the stump of David: Isa. 11.1, 53.2).

Note: The resultant colour scheme reminds me of a toothpaste logo, which was unintentional.

Still, the question remains, How can both Matthew and Luke’s genealogies be said to be historically accurate?

Still, the question remains, How can both Matthew and Luke’s genealogies be said to be historically accurate?

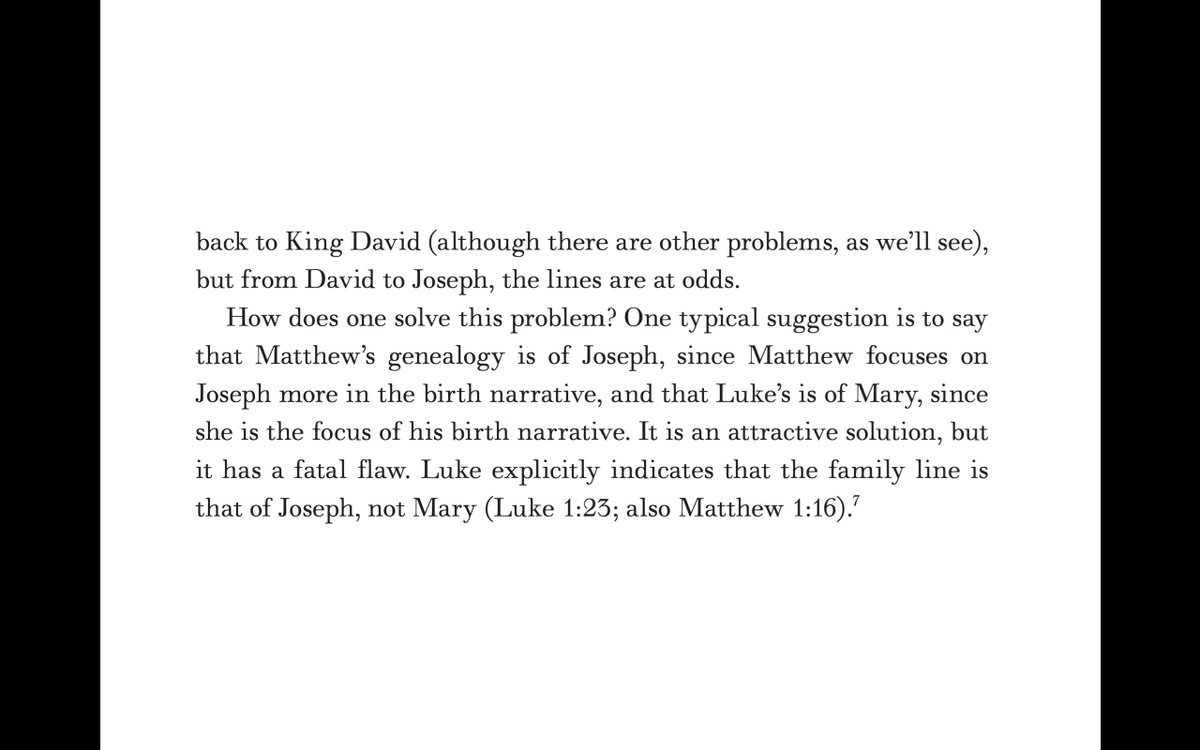

Some scholars view one of the genealogies as Joseph’s and the other as Mary’s.

As Ehrman points out, however, the text of Scripture doesn’t actually suggest *either* genealogy is Mary’s.

As Ehrman points out, however, the text of Scripture doesn’t actually suggest *either* genealogy is Mary’s.

Besides, even if Matthew and Luke’s genealogies differed between Matthan-aka-Matthat and Zerubbabel because one of them was Mary’s, it wouldn’t explain why they differed between Shealtiel and David.

We therefore need another explanation.

We therefore need another explanation.

So, what else could explain why a person has two different genealogies?

One possibility is a levirate marriage (cp. Deut. 25).

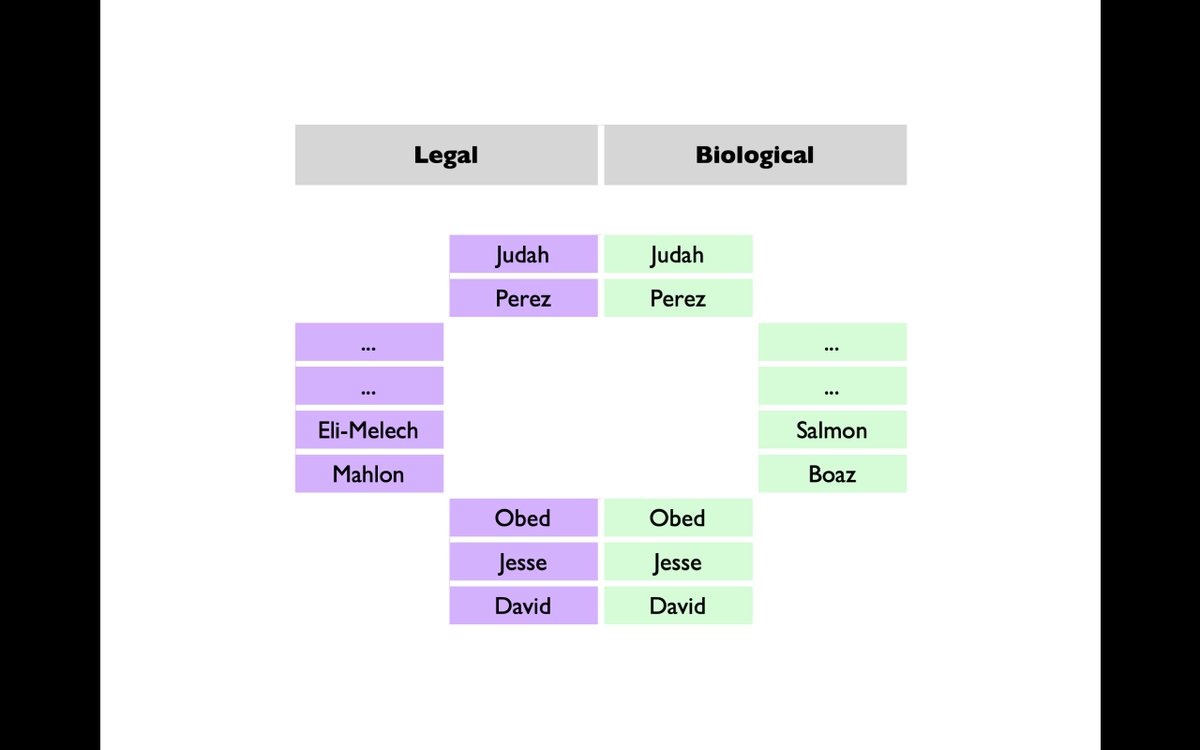

Consider Boaz and Ruth.

Due to Boaz’s (levirate) marriage to Ruth, Obed’s genealogy can be reckoned in two different ways.

One possibility is a levirate marriage (cp. Deut. 25).

Consider Boaz and Ruth.

Due to Boaz’s (levirate) marriage to Ruth, Obed’s genealogy can be reckoned in two different ways.

Boaz acquired Ruth as his wife in order to ‘perpetuate the name’ of Mahlon (Ruth 4.10). Consequently, Obed can be referred to as ‘a son of Mahlon, the son of Eli-Melech (etc.)’.

Biologically, however, Obed was ‘the son of Boaz, the son of Salmon (etc.)’.

Biologically, however, Obed was ‘the son of Boaz, the son of Salmon (etc.)’.

The same kind of situation pertains when someone is adopted.

For instance, Mordecai is said to have taken Esther ‘as his daughter’ (Est. 2.7).

Consequently, Esther’s ancestry can be traced either through Mordecai the son of Jair (Est. 2.5) or through Esther’s biological father (a different son of Jair).

Consequently, Esther’s ancestry can be traced either through Mordecai the son of Jair (Est. 2.5) or through Esther’s biological father (a different son of Jair).

The question, then, is whether we have any reason to think *Jesus’* genealogy involves such events.

And the answer is, Yes, we do.

We don’t have an *explicit* references to a levirate marriage or an adoption,...

And the answer is, Yes, we do.

We don’t have an *explicit* references to a levirate marriage or an adoption,...

...but Jesus’ genealogy is marked out by five distinct oddities, which, when considered as a whole, are suggestive of the incidence of both a levirate marriage *and* an adoption in Jesus’ ancestry.

We’ll consider each oddity in turn.

We’ll consider each oddity in turn.

🔹 ODDITY #1: Jesus is a descendant of Jeconiah.

In the book of Jeremiah, God chastises Jeconiah’s father (Jehoiakim) for his wanton lifestyle.

In the book of Jeremiah, God chastises Jeconiah’s father (Jehoiakim) for his wanton lifestyle.

‘Even if your son was a signet ring on my right hand’, God says, ‘I would still tear you off...and give you into the hand of Nebuchadnezzar!’ (Jer. 22.24).

In other words, Jehoiakim’s time is up. And even if his son Jeconiah had been a saint, it couldn’t have saved his reign. (Jer. 36.30 complicates things—more on that some other time.)

God then goes on to criticise Jeconiah himself.

‘Register this man as childless!’, God says to the Temple genealogists. ‘None of his seed are to succeed him on the throne of David!’ (Jer. 22.30).

‘Register this man as childless!’, God says to the Temple genealogists. ‘None of his seed are to succeed him on the throne of David!’ (Jer. 22.30).

Not only will Jeconiah’s father be exiled; Jeconiah’s descendants will lose their right to inherit the throne of David (due to their father’s sin).

A Messiah who arises from the line of Jeconiah is, therefore, a difficult notion.

A Messiah who arises from the line of Jeconiah is, therefore, a difficult notion.

And its difficulty isn’t a point to which critics of the Bible have needed to draw our attention; Matthew draws our attention to it perfectly adequately himself.

In the first verse of his Gospel, he introduces us to Jesus as the one who will fufill God’s promise to King David…

In the first verse of his Gospel, he introduces us to Jesus as the one who will fufill God’s promise to King David…

…and, immediately afterwards, he sets out a record of Jesus’ ancestry, which excludes at least three Judean kings and yet declines to exclude Jeconiah.

Matthew even associates the rise of Jeconiah with a pivotal moment in history, which draws further attention to it.

Why?

Matthew even associates the rise of Jeconiah with a pivotal moment in history, which draws further attention to it.

Why?

🔹ODDITY #2: Jeconiah has a number of sons.

Despite the fact Jeconiah is rendered ‘childless’ by Jeremiah’s curse, he has seven sons (the ideal number: cp. Ruth 4.15, Job 1.2, 42.13).

How come?

Despite the fact Jeconiah is rendered ‘childless’ by Jeremiah’s curse, he has seven sons (the ideal number: cp. Ruth 4.15, Job 1.2, 42.13).

How come?

🔹ODDITY #3: Shealtiel is singled out among Jeconiah’s sons for some reason.

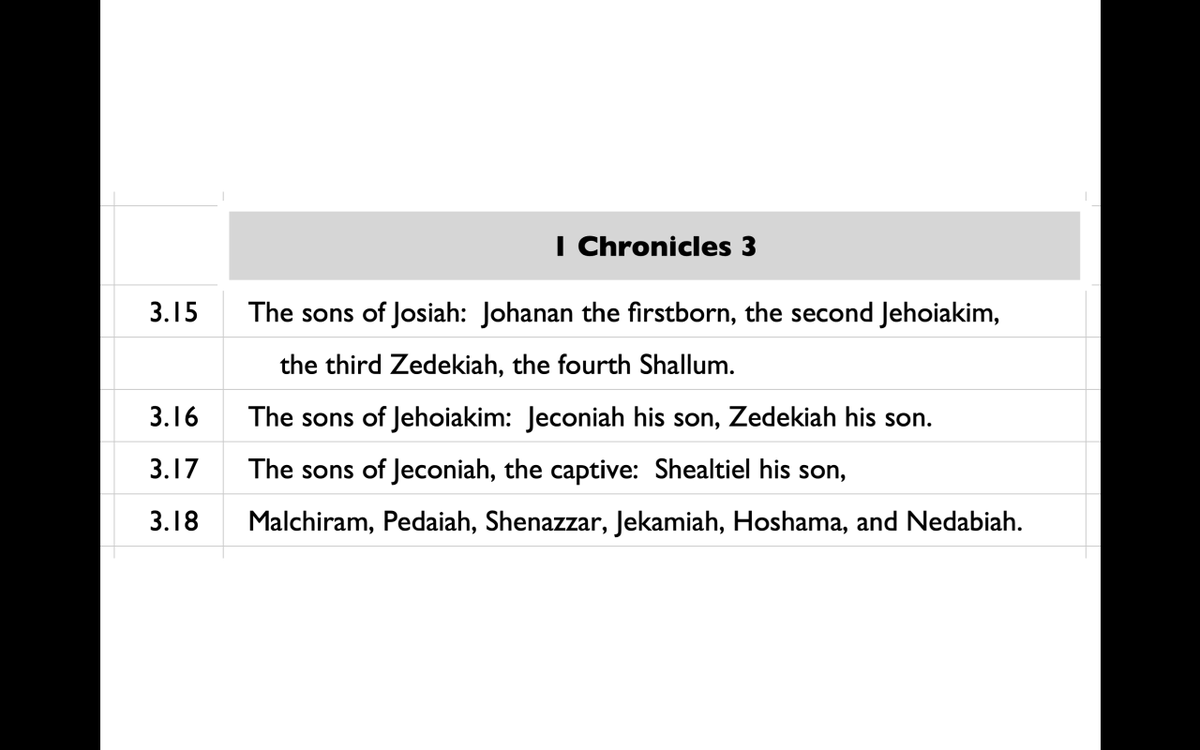

By and large, Scripture is quite happy to repeat itself, and the text of 1 Chron. 3 is no exception.

The son of each Judean king is explicitly referred to as ‘his son’ (i.e., the son of his father).

By and large, Scripture is quite happy to repeat itself, and the text of 1 Chron. 3 is no exception.

The son of each Judean king is explicitly referred to as ‘his son’ (i.e., the son of his father).

Oddly, however, that pattern breaks down when we get to 3.18.

Shealtiel is referred to as Jeconiah’s son (3.17), yet his other six sons are not, which is notable.

Shealtiel is referred to as Jeconiah’s son (3.17), yet his other six sons are not, which is notable.

And when the text of Scripture establishes a pattern and then (deliberately) deviates from it, we should take note of it.

What’s special about Shealtiel isn’t stated, but something clearly is.

What’s special about Shealtiel isn’t stated, but something clearly is.

🔹 ODDITY #4: Zerubbabel looks to have been the product of a levirate marriage.

Recall the text of 1 Chr. 3.17–19 (scroll up a bit).

Given 1 Chr. 3.17–19, if we were asked to chart out Jeconiah’s family tree, we’d probably come up with something like the tree shown below.

Recall the text of 1 Chr. 3.17–19 (scroll up a bit).

Given 1 Chr. 3.17–19, if we were asked to chart out Jeconiah’s family tree, we’d probably come up with something like the tree shown below.

Yet, outside of 1 Chr. 3, Zerubbabel is never referred to as the son of Pedaiah; he’s invariably referred to as the son of *Shealtiel*.

It thus looks as if Shealtiel’s brother Pedaiah raised up a son on his behalf in order to perpetuate his line, per the tree below.

🔹 ODDITY #5: In the book of Haggai, God says he’ll make Zerubbabel into exactly the kind of son Jeconiah *should* have been.

Only two people in Scripture are likened to signet rings—Jeconiah and Zerubbabel.

In Jeremiah, Jeconiah is told he *should* have been like a signet ring on God’s right hand (but wasn’t).

In Jeremiah, Jeconiah is told he *should* have been like a signet ring on God’s right hand (but wasn’t).

Then, after the exile, God says he’ll make Zerubbabel like a signet ring—or perhaps even like that particular signet ring (כַּחוֹתָם).

Zerubbabel will thus be what Jeconiah *should* have been.

Zerubbabel will thus be what Jeconiah *should* have been.

We can sum up these five oddities as follows.

#1: Jesus is the descendant of Jeconiah—a man who is pronounced ‘childless’ and whose descendants are disqualified from the throne.

#2: Though pronounced childless, Jeconiah is said to have sons.

#1: Jesus is the descendant of Jeconiah—a man who is pronounced ‘childless’ and whose descendants are disqualified from the throne.

#2: Though pronounced childless, Jeconiah is said to have sons.

#3: One of those sons—Shealtiel—is not like Jeconiah’s other sons for some reason.

#4: Shealtiel’s son (Zerubbabel) is the product of a levirate marriage (or similar).

#5: Zerubbabel fulfils Jeconiah’s intended destiny (as a ‘signet ring’).

#4: Shealtiel’s son (Zerubbabel) is the product of a levirate marriage (or similar).

#5: Zerubbabel fulfils Jeconiah’s intended destiny (as a ‘signet ring’).

These oddities invite explanation, and, happily, they can be explained by a plausible historical scenario.

The relevant scenario consists of four components. Two are explicitly set out in Scripture, and two are inferred/hypothesised on the basis of Scripture.

The relevant scenario consists of four components. Two are explicitly set out in Scripture, and two are inferred/hypothesised on the basis of Scripture.

🔹 COMPONENT #1:

Although Jeconiah’s life began badly, Jeconiah came good in the end.

Jeremiah called Judah’s kings not to resist the might of Nebuchadnezzar but to surrender to him (in which case both their lives and their land would be spared: Jer. 21.8ff.),

Although Jeconiah’s life began badly, Jeconiah came good in the end.

Jeremiah called Judah’s kings not to resist the might of Nebuchadnezzar but to surrender to him (in which case both their lives and their land would be spared: Jer. 21.8ff.),

and Jeconiah did so (2 Kgs. 24.12). Rather than stay and fight, he handed himself over to Nebuchadnezzar, and Nebuchadnezzar spared his life, just as God said he would (cp. Jer. 52.31–34).

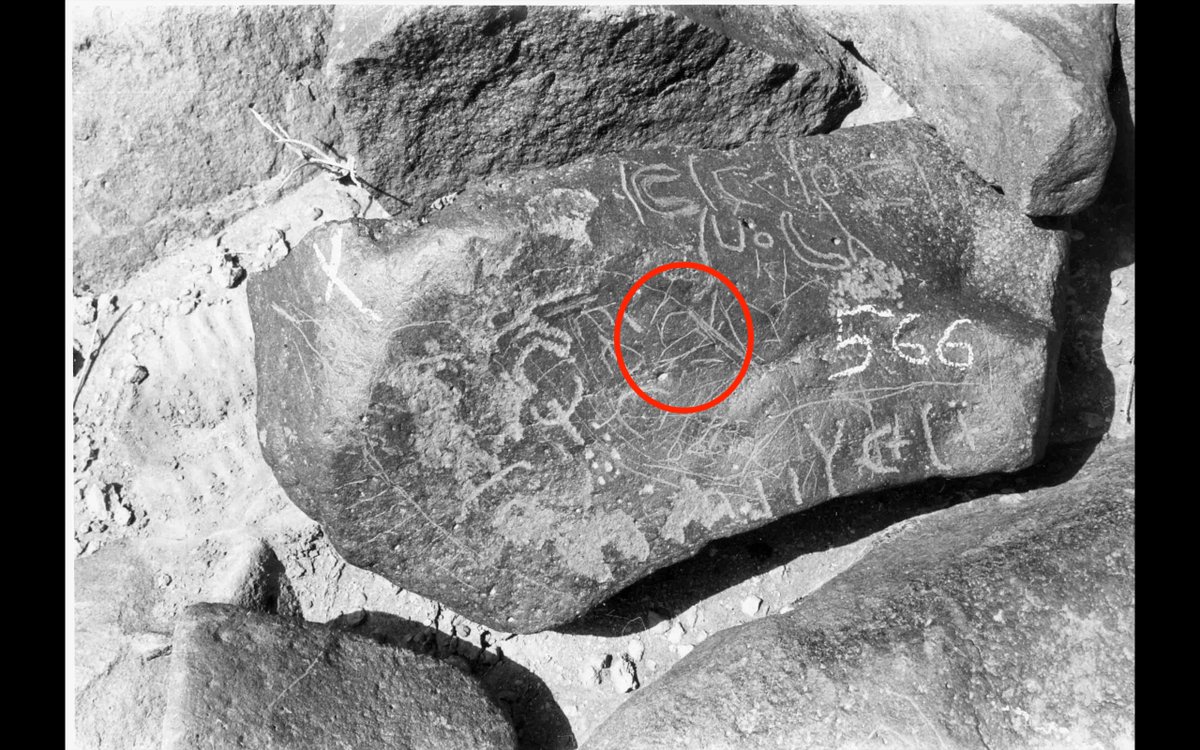

Indeed, God gave him great favour in Nebuchadnezzar’s eyes. On a Babylonian ration tablet (dated to the year 591 BC), Jeconiah is assigned over six times as large a quantity of rations of anyone else on the tablet:

Moreover, although Jeconiah later ended up in prison, God raised him up, which is the note on which Jeremiah’s prophecies conclude (Jer. 52.31–34).

🔹 COMPONENT #2:

When Jeconiah repented, God repented—that is to say, God rescinded Jeremiah’s prophecy against Jeconiah.

That God rescinded Jeremiah’s prophecy isn’t explicitly stated in the text of Jeremiah,...

When Jeconiah repented, God repented—that is to say, God rescinded Jeremiah’s prophecy against Jeconiah.

That God rescinded Jeremiah’s prophecy isn’t explicitly stated in the text of Jeremiah,...

... but it provides a plausible explanation both for Chronicles’ reference to Jeconiah’s sons (1 Chr. 3.17–18) and for Haggai’s reference to Zerubbabel as a ‘signet ring’,

and it’s makes sense of the flow of Jeremiah’s prophecies.

and it’s makes sense of the flow of Jeremiah’s prophecies.

Throughout the book of Jeremiah, where there’s repentance, there’s hope (e.g., 7.5ff., 17.24ff., 22.4ff.), even when it seems as if the die’s already been cast.

When a nation changes its ways, God changes its destiny (Jer. 18).

When a nation changes its ways, God changes its destiny (Jer. 18).

Hence, when Jeconiah hands himself over to Nebuchadnezzar, we can assume God rewrites Jeconiah’s destiny (a point we’ll pick up later).

Indeed, in Jeremiah 24, when Jeconiah surrenders to Nebuchadnezzar,...

Indeed, in Jeremiah 24, when Jeconiah surrenders to Nebuchadnezzar,...

...God explicitly identifies him as one of the ‘good figs’ who are to be ‘planted’ and ‘built up’ in Babylon,

all of which follows directly on from God’s promise to raise up a righteous branch from the line of David (23.5ff.).

all of which follows directly on from God’s promise to raise up a righteous branch from the line of David (23.5ff.).

🔹 COMPONENT #3:

In exile, Jeconiah fathered six sons and adopted a seventh named Shealtiel (hence Matt. 1.12 situates Shealtiel’s ‘birth’ after the exile),

which explains why Shealtiel is singled out in the text of 1 Chr. 3.17–18. Shealtiel wasn’t like Jeconiah’s other sons.

In exile, Jeconiah fathered six sons and adopted a seventh named Shealtiel (hence Matt. 1.12 situates Shealtiel’s ‘birth’ after the exile),

which explains why Shealtiel is singled out in the text of 1 Chr. 3.17–18. Shealtiel wasn’t like Jeconiah’s other sons.

The ‘birth’ of Shealtiel was highly significant.

When God rescinds a curse, he doesn’t simply pretend the curse was never uttered; he provides a *basis* on which it can be subverted/redirected.

When God rescinds a curse, he doesn’t simply pretend the curse was never uttered; he provides a *basis* on which it can be subverted/redirected.

Nineveh might not have been ‘overthrown’ (נהפכת), but it was נהפכת-ed in a different sense (‘converted’) (Jon. 3).

And not all those who have sinned have received the wages of sin (death), but death has been the consequence of their sin (Rom. 6).

And not all those who have sinned have received the wages of sin (death), but death has been the consequence of their sin (Rom. 6).

God subverted Jeconiah’s curse in a similar manner.

Shealtiel had a legal/adopted line (set out in Matthew) which connected him to the kings of Judah, and he had a biological line (set out in Luke) which connected him to David via Nathan (cp. Luke 3.31 w. 1 Chr. 3.5, Zech. 12.12).

Hence, by means of Jeconiah’s adoption of Shealtiel, God provided a means by which David’s kingly line could continue and yet Jeconiah’s curse could be avoided.

And, in case anyone wondered if it was appropriate for a merely legal descendant of the kingly line to sit on David’s throne, God introduced a further layer of complexity into the equation, as we’ll now consider.

🔹 COMPONENT #4

Shealtiel died before he fathered any children, so one of Jeconiah’s biological sons (Pedaiah) raised up a child in his name (Zerubbabel).

Shealtiel died before he fathered any children, so one of Jeconiah’s biological sons (Pedaiah) raised up a child in his name (Zerubbabel).

That brought about a curious situation.

Zerubbabel was the ‘seed’ of many different people.

Zerubbabel was the ‘seed’ of many different people.

By name, he was ‘the seed of Babylon’ (or perhaps ‘sown in Babylon’). Legally, he was the seed of Jeconiah. And, biologically, he was the seed of both Shealtiel and Jeconiah (through Pedaiah).

Meanwhile, the names of Zerubbabel’s legal and biological parents were Shealtiel and Pedaiah, which translate as ‘I borrowed (him from) God’ and ‘God redeemed (us)’!

Hence, in the rise of Zerubbabel, God fulfilled his word through Jeremiah. He regathered his flock, assigned shepherds over them (Zerubbabel and Jeshua), and in the process raised up a righteous branch from David’s progeny (Jer. 23.1–8).

CONCLUSION

The scenario outlined above provides a possible explanation of why Matthew and Luke connect Shealtiel back to David via different genealogical lines.

The scenario outlined above provides a possible explanation of why Matthew and Luke connect Shealtiel back to David via different genealogical lines.

It doesn’t explain *every* difference in their genealogies, nor does it seek to. (The differences between Matthan-aka-Matthat and Zerubbabel still need to be addressed.) It does, however, serve at least three significant purposes.

First, it undercuts the claim that Matthew and Luke’s genealogies are incoherent.

Second, it lends credibility to Matthew and Luke’s genealogies.

Matthew and Luke’s genealogies exhibit the kind of complexity we’d expect to find in genealogies which span over a thousand years,...

Matthew and Luke’s genealogies exhibit the kind of complexity we’d expect to find in genealogies which span over a thousand years,...

...and their complexity occurs when we would expect it to, i.e., at a tumultuous moment in Judah’s history.

Moreover, when we have background information at our disposal (i.e., in the events prior to Jerusalem’s fall), it enables us to make sense of Matthew and Luke’s genealogies,...

...which gives us reason to trust them when we don’t have such information at our disposal (i.e., over the inter-testamental period).

Third, it sheds light on the purpose of Matthew and Luke’s genealogies.

Matthew draws our attention to Jeconiah for a reason.

Matthew draws our attention to Jeconiah for a reason.

By means of Jeconiah’s adoption of a son, God brought redemption to a fallen line,

which is exactly what he would do in the lives of Joseph and Jesus.

By means of Joseph’s adoption of Jesus, God would bring redemption to an entire race (Matt. 1).

which is exactly what he would do in the lives of Joseph and Jesus.

By means of Joseph’s adoption of Jesus, God would bring redemption to an entire race (Matt. 1).

Meanwhile, Luke draws our attention *away* from Jeconiah, which he too does for a reason.

Just as God raised up an obscure branch of David’s progeny to supplant Judah’s failed leaders, so in and through Jesus’ ministry God would raise up the poor and downtrodden to supplant the failed leaders of Jesus’ day (Luke 1–2).

As such, Matthew and Luke’s genealogies constitute the perfect introductions to their Gospels, not despite their oddities, but because of them.

THE END.

THE END.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh