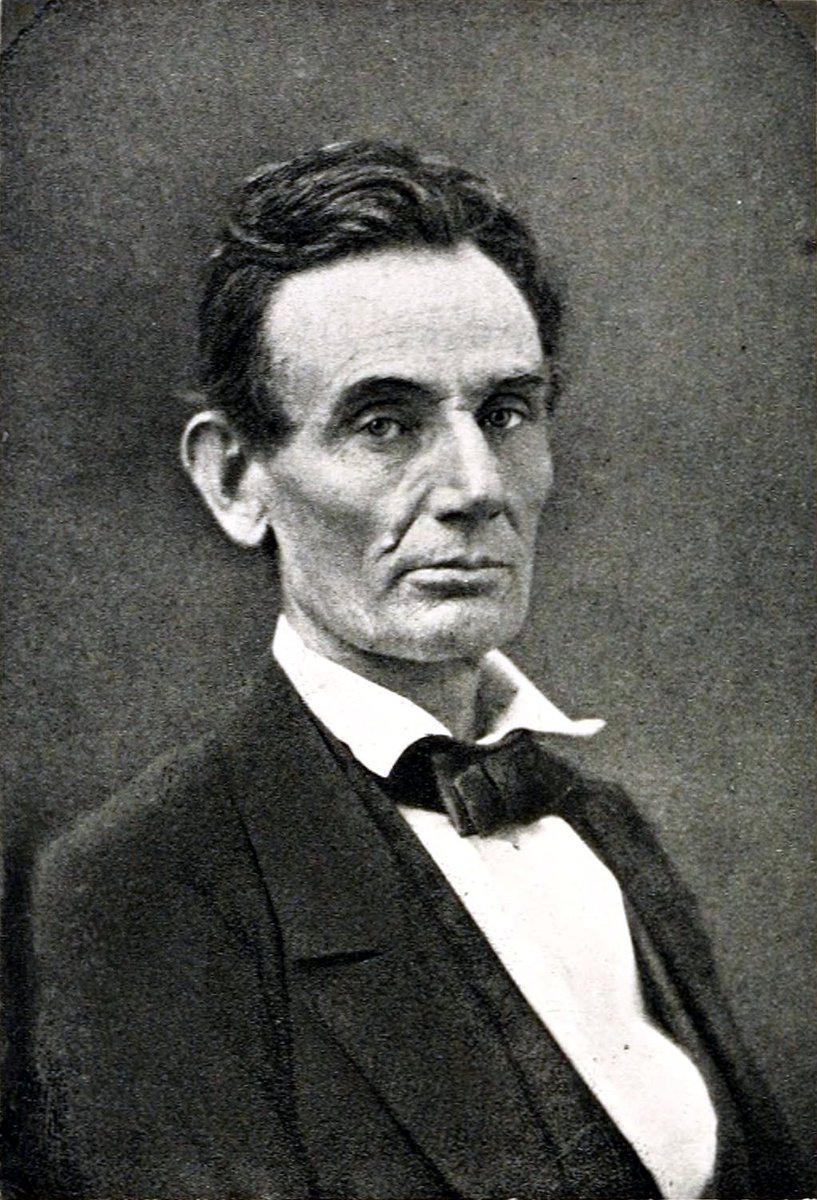

As a follow up to yesterday’s #Juneteenth thread, here’s a 🧵about the time Abe Lincoln made a distributist 🐄 argument against slaveholders and secession.

You may have seen these words before. Everybody from conventional progressives to socialists like this quote. We’ve posted it before ourselves.

But there’s more to the context than most people make out, and it still matters to us today.

But there’s more to the context than most people make out, and it still matters to us today.

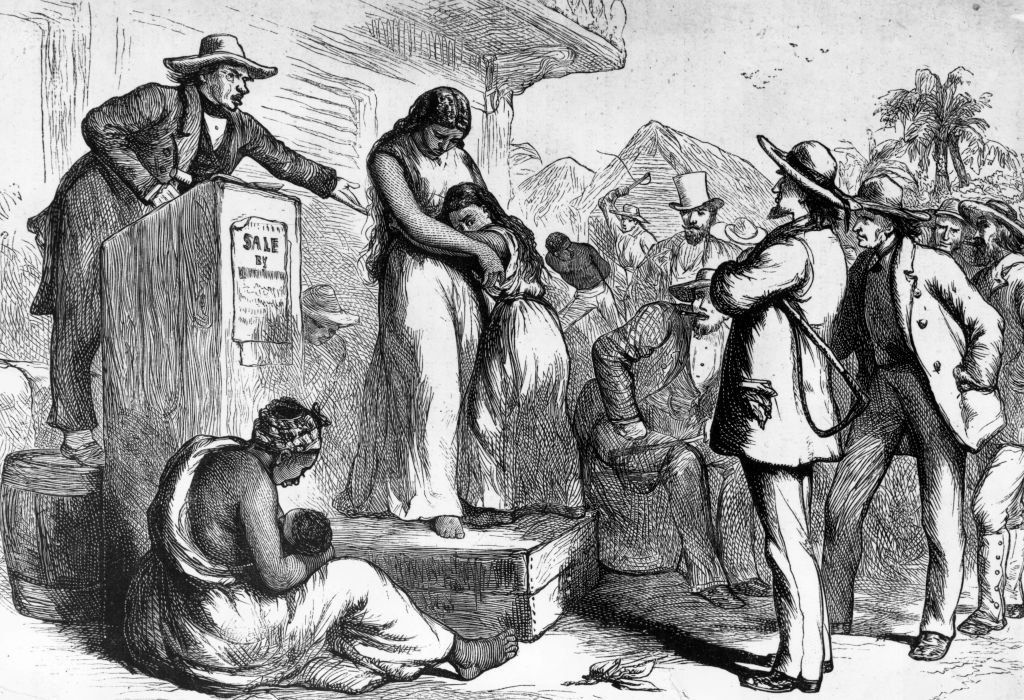

Lincoln made this statement shortly after the Civil War began. He was responding to arguments that the South–and in particular its slaveholding planters–had the right to form a new government to represent the interests of “capital” that the prosperity of the country depended on.

Apologists for slavery liked to argue that it was natural for laboring people to be subordinated to people who owned things. They claimed slavery wasn’t fundamentally different than the relationship between Northern factory owners and their workers (many argued it was better).

Obviously there were lots of problems with this equivalence. But Lincoln denied that capital was entitled to dominate labor: “capital has its rights,” he said, but labor comes first. No economy and no society can exist without people who work.

But there was another problem.

But there was another problem.

The secessionists were wrong, Lincoln said, in supposing that there was or ought to be a total separation between capital and labor, between wealth and work. That was not the America he knew.

In the America he knew and championed, millions of free laborers could mix their own little bit of capital with their labor.

They owned small farms, shops, workshops, working alongside their families and, in theory at least, answering to nobody else for their own prosperity.

They owned small farms, shops, workshops, working alongside their families and, in theory at least, answering to nobody else for their own prosperity.

This kind of broad-based prosperity was a uniquely American phenomenon in its day, and it helped make a democratic society possible by giving millions of citizens a degree of economic independence.

Lincoln did acknowledge that many people were hired laborers working for wages; but, he said, this was not at all like slavery, insofar as hired men could expect to save up money and eventually go into business for themselves.

“The prudent, penniless beginner in the world labors for wages awhile, saves a surplus with which to buy tools or land for himself…and at length hires another new beginner to help him. This is the just and generous and prosperous system which opens the way to all.”

This is an important point: Lincoln’s defense of the dignity of wage labor rests on it being a temporary condition. The ultimate goal and the economic norm in this way of thinking is still ownership.

So for Lincoln, free labor as an alternative system to slavery was *first and foremost* about working directly for the benefit of one’s self and one’s family. Trading labor for another’s profit was not the ideal.

Now, there are some legitimate criticisms you can make of this free labor ideal. It was never shared by absolutely everyone: not least, it often implicitly depended on the dispossession of the people who used to live where those millions of white small farmers made their homes.

But the kind of broad-based ownership and prosperity Lincoln was describing was real, and did help to make the American experiment something unique in the history of the world.

By Lincoln’s day that was starting to change, though, and it would change more after his death: industrialism created huge amounts of wealth but also concentrated much of it in a small number of hands, and produced a huge working class permanently dependent on wage work.

It’s unclear how much of this Lincoln foresaw, or how he would have responded if he had lived longer. What it is clear is that this isn’t the system he defended. Indeed, we can find in his words tools to critique that system & our own postindustrial economy that has replaced it.

A free economy, as Lincoln understood it, was not primarily about empowering capital, but about empowering individuals & families to better themselves through both labor & ownership. He understood that was the kind of economic life that befits a free people.

Still true today!

Still true today!

@threadreaderapp Unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh