Thread: American Civil War and the Tragedy of Missed Lessons

There was an even 100 years between the downfall of Napoleon in 1814 and the beginning of World War One in 1914. The American Civil War was the largest conflict fought in that intervening century. (1)

There was an even 100 years between the downfall of Napoleon in 1814 and the beginning of World War One in 1914. The American Civil War was the largest conflict fought in that intervening century. (1)

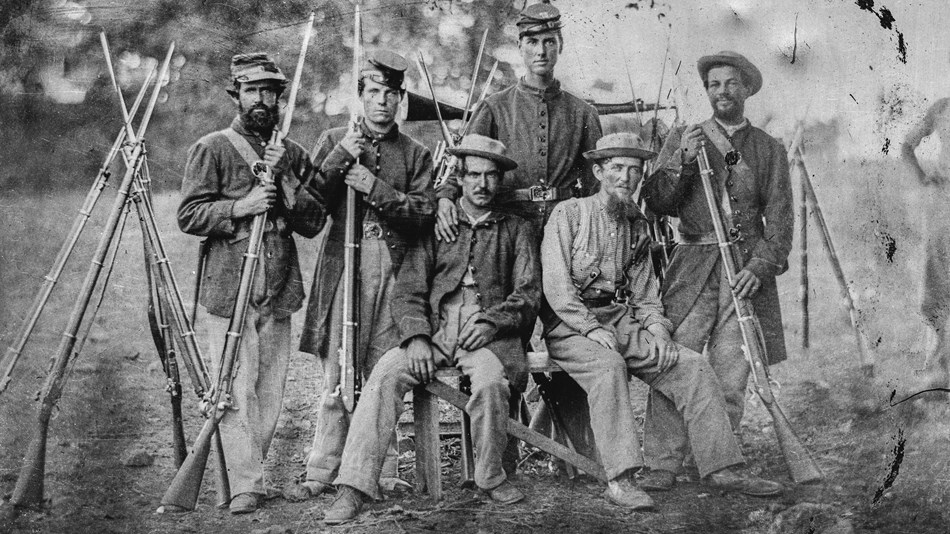

The Civil War featured incredibly large armies fighting in theaters that were very widely spread out, with major battles taking place from Pennsylvania to Texas. The war also displayed early use of new technologies like railroads, telegraphs, and mass produced rifles. (2)

While no foreign states became actively involved in the conflict, the war was witnessed by foreign military observers. Despite their front row view of this major conflict, Europe failed to learn important lessons about the trajectory of warfare. (3)

The Civil War provided a very clear look at the movement towards the high intensity trench warfare that would become the defining characteristic of World War One. (4)

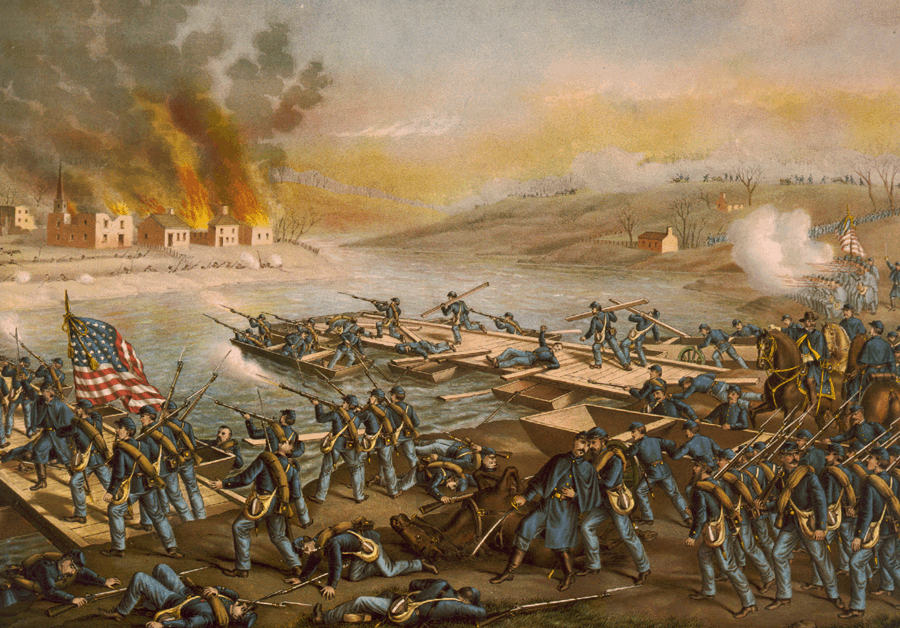

At the Battle of Fredericksburg in 1862, the Confederates absolutely mauled a much larger Union army, when the Union forces attempted frontal assaults on entrenched southern infantry. The loss ratios for the battle were a full 2 to 1 in favor of the south. (5)

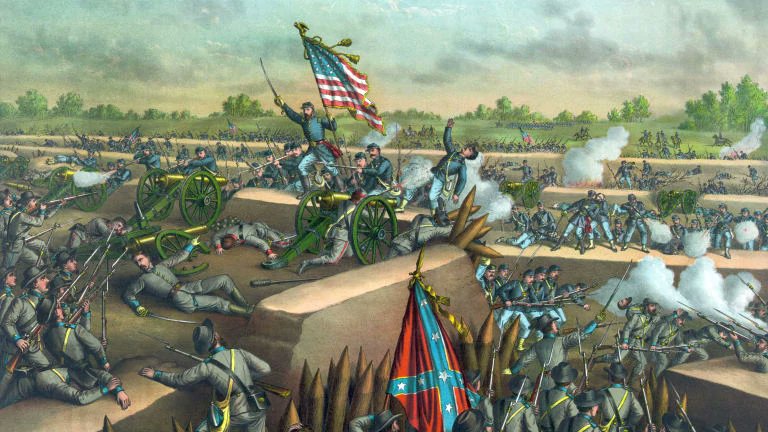

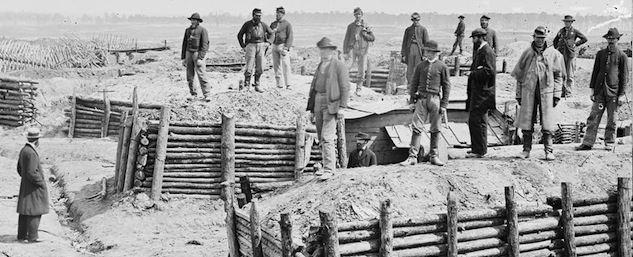

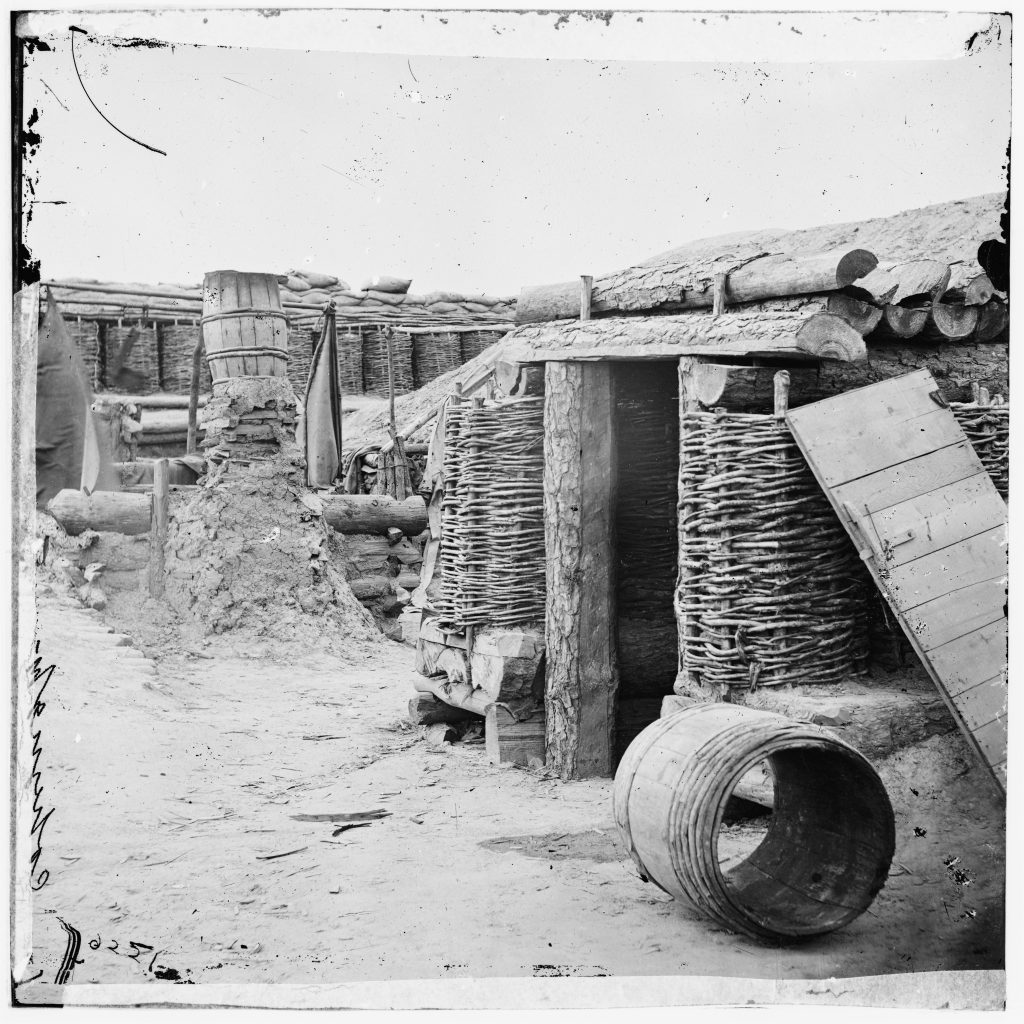

Later in the war, the Union defeated the Confederacy in a long, grinding series of battles collectively known as the "Siege of Petersburg." This was a preview of World War One. Both sides made heavy use of trenches, forcing a slow and bloody battle. (6)

Petersburg was nothing like the set piece battles of the past that could be resolved quickly; the entire struggle took over nine months and was characterized by heavy artillery fire and extensive earthworks. Both sides took losses of over 30% of their total forces. (7)

The long, slow moving affair at Petersburg foreshadowed both the mass casualties and the agonizingly drawn out nature of WW1 meatgrinder warfare. The nine month battle was similar to battles like Verdun or Gallipoli, which stretched out over nearly a full year. (8)

European military observers saw battles like these, but it completely failed to register that war in Europe would soon be like this as well. They generally dismissed the use of fortifications as an aberration born from poor training of American officers. (9)

One Prussian officer who observed the war noted the widespread “use of shovel and axe, exploiting the skill every American has with these tools." His notion was that entrenchment was due to unique American characteristics, and a compensation for their poor tactical skills. (10)

One interesting Prussian argument was that trenches were devised as a way to keep officers and troops safe while they considered their next move - they were thus unnecessary for a Prussian army that could make quick decisions and react instantly in the field. (11)

The Prussians won an enormous victory over the French only six years after the end of the Civil War, and they did it by applying traditional Prussian offensive principles. The Franco-Prussian War allowed European military planners to ignore the American War. (12)

The general conclusion in Europe was that everything aberrant in the American War happened because the Americans were undisciplined and unprofessional. One French observer decided that “The war of secession has not furnished anything new worthy of study and imitation.” (13)

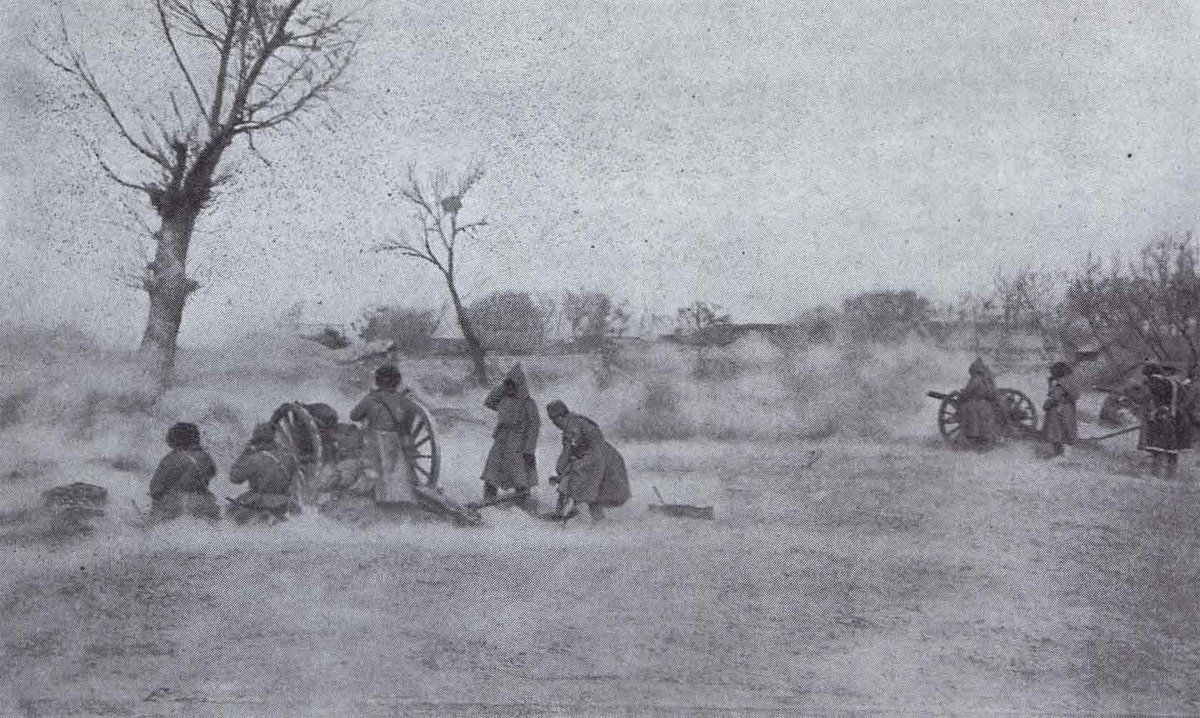

Europe got one more preview of the World War. In early 1905, Japan and Russia fought a colossal battle in Manchuria called the Battle of Mukden. This was one of the largest battles that had ever been fought, with nearly 300,000 men fielded on both sides. (14)

Mukden was notable for the astonishing, unprecedented amount of ordinance that was used. The Japanese alone fired almost 28,000 artillery shells per day during the ten day battle. Huge casualties were amassed to make small advances. (15)

As in the case of the American war, Europeans failed to learn lessons from the Russo-Japanese conflict. The war was dismissed as a contest between two "Asiatic", and by extension barbarous peoples, and thus the fighting could not be extrapolated to Europeans. (16)

The Europeans got a rude awakening in 1914, when they attempted to fight a traditional war of spirited and crisp offensive movement, and instead they got trenches and mud and endless shelling and ten million dead. (17)

Arrogance and the belief that there was little to be learned from wars between unsophisticated inferiors allowed Europe to wander blindly into a military and civilizational catastrophe. Talk about learning things the hard way. (18)

For more reading on this, I recommend "The Military Legacy of the Civil War: The European Inheritance" by Jay Luvaas. As far as I know this is the only work dedicated solely to the study of European observation of the American Civil War, and the lessons they chose not to learn.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh