With a slew of #SCOTUS opinions comes lots of great #legalwriting examples!

In Justice Kagan's Wooden v. U.S. opinion, let's break down three simple tools we can all use:

1. TLDR Intros

2. Simple Sentences

3. Trendy Transitions

1/x

In Justice Kagan's Wooden v. U.S. opinion, let's break down three simple tools we can all use:

1. TLDR Intros

2. Simple Sentences

3. Trendy Transitions

1/x

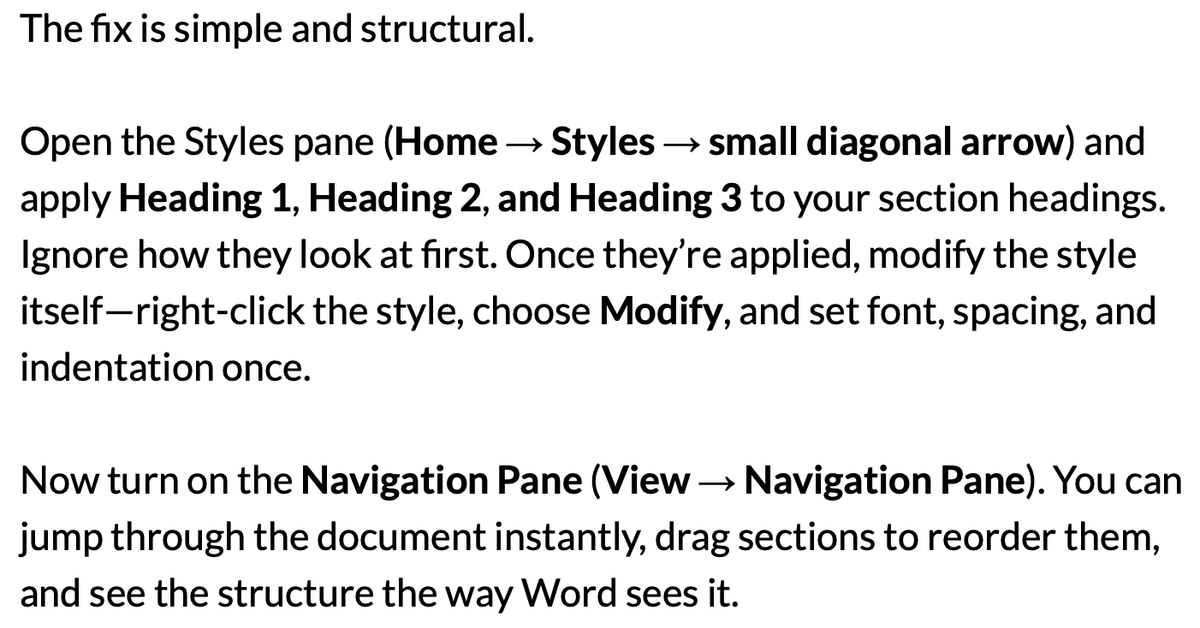

TLDR Intros (quick intros that dish the key points in a document) are now common with judges and lawyers alike.

How do the greats craft them?

1. Give readers context - why is this dispute here?

2. Insert choice details to prime

3. Highlight your legal pitch

How do the greats craft them?

1. Give readers context - why is this dispute here?

2. Insert choice details to prime

3. Highlight your legal pitch

In a paragraph, Justice Kagan orients you to the situation and highlights several charged facts:

(1) that the defendant faces a hefty 15-year sentence,

(2) that the lower court is piling on 20 years after the fact, and

(3) this was a single facility on a single evening.

(1) that the defendant faces a hefty 15-year sentence,

(2) that the lower court is piling on 20 years after the fact, and

(3) this was a single facility on a single evening.

She also includes her key legal pitch: It's absurd to base a statutory trigger on distinct moments in time rather than a common-sense understanding of a single event.

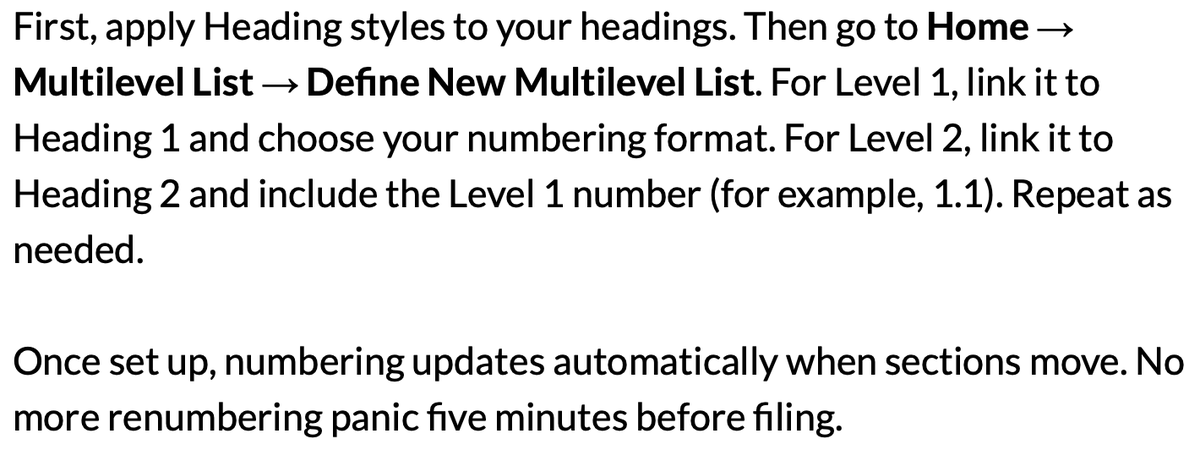

Great legal writers spoon-feed ideas to readers - using sentences that tend toward the simple. Many of the best sentences are so simple all they need is a period.

When great writers get more complex and pack more groups of words (and ideas) into a sentence, they have a reason.

When great writers get more complex and pack more groups of words (and ideas) into a sentence, they have a reason.

The first sentence is a simple clause.

The second sentence offers two simple, related ideas.

The third sentence is again only two groups of words and a simple structure (a phrase with some context to set the scene for the officer's visit)...

The second sentence offers two simple, related ideas.

The third sentence is again only two groups of words and a simple structure (a phrase with some context to set the scene for the officer's visit)...

The fourth sentence is another simple single-clause sentence. And then when we finally get a few groups of words in the fifth sentence, it's crafted complexity. A narrative sentence meant to convey unfolding events and a scene.

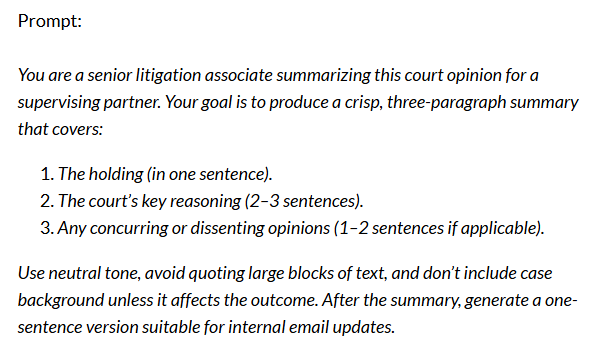

Finally, the greats often do two things with transitions.

First, transition by adding helpful guides to your sentences - don't just insert empty transitions like "furthermore" that tell readers "another point is coming."

First, transition by adding helpful guides to your sentences - don't just insert empty transitions like "furthermore" that tell readers "another point is coming."

Second, vary your transition phrases throughout your document so that readers don't notice them. And vary also by echoing words or concepts from the prior sentence (instead of always relying only on transition phrases).

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh