Remember a few weeks ago when I gave a lecture @imc_leeds about my reconstruction of the Beauvais Missal & announced that leaf no. 113 had landed in my inbox the day before? Now that I’m caught up on other things, I can work on placing it in the reconstruction. Here’s how…

https://twitter.com/lisafdavis/status/1544262870304694274

Step 1: identify recto & verso. Generally a straightforward task…look for the binding holes (i.e. the gutter), which, in a manuscript that reads left -> right will be on the left of the recto side. In this case, the leaf is heavily trimmed on all sides, so no binding holes!

No binding holes, no problem. Just look at the text, and figure out which side continues the text from the other. In this case, though, the leaf is framed and only one side is visible! How to tell recto from verso, then? Is it impossible? Certainly not!

The parchment on which the Beauvais Missal is written is fairly translucent, so you can see the text on the other side (which I’ll call Side B). By inverting the image of Side A and playing around with the contrast, much of the other side can be read!

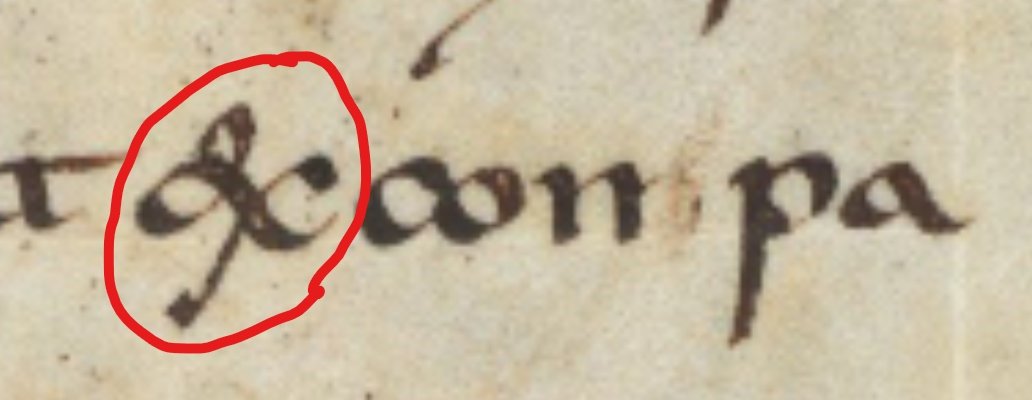

I can see, for example, that the final letters of Side B are “adiuto…” Side A starts with “…rium super potentem…” Google reports that there is indeed a liturgical text that reads “Posui adiutorium super potentem…”! So now we know that Side B is the recto, & A is the verso!

But now we know even more. I already knew that it was from the Commons, as it gives multiple options for a single genre of chant, in this case, Alleluias and Verses. By searching the CANTUS database, we can identify this leaf as coming from the Common of One Confessor!

But wait, there’s more! My Fragmentarium reconstruction of the Beauvais Missal includes several leaves from the Common of One Confessor. Might this new leaf be consecutive with any of them? fragmentarium.ms/overview/F-4ihz

Having identified the texts on the leaf, I know what words should come immediately before and after: “…iuravi David ser…” before, and “…dinem melchisedech” after. One of the two leaves @Cleveland_PL is also from the Common of Confessors and ends with “iuravi Davis ser…”!

There’s more evidence tying these leaves together. Here’s the verso of the Cleveland leaf next to the inverted image of the new leaf. The red rectangles show where the initials from the recto of the new leaf have left inverted offsets on the verso of the Cleveland leaf!

And now we have all the information we need to place this new leaf into the reconstruction: we've distinguished recto/verso; identified the liturgy; and found a consecutive leaf! Once I have images of both sides (soonish), I’ll add them to Fragmentarium. 113 down, 196 to go!

More on this #fragmentology project here: brokenbooks2.omeka.net

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh