First things first. Mothers Pride is not a Scottish brand - it's from Manchester and dates to 1932. When the industry consolidated in the 1950s-70s, big companies took over medium-sized regional bakers and applied their brands to them (see also Sunblest) flickr.com/photos/3684428…

Second things second. "Plain Bread" was not, originally, a peculiarly Scottish term. But it is one that has become over time almost universally associated with a specific style of Scottish batch-baked bread, with its closest relations in styles of Irish bread.

🏴🤝🇮🇪

🏴🤝🇮🇪

So what is plain bread and how did it become to be the loaf with such a strong national identity that it is known for today? And why?

The term "plain bread" derives from a Bread Acts in the early part of the 19th century, starting in 1822. Governments have long sought to regulate pricing and quality of bread, going right back to medieval times, in recognition of it being so essential a foodstuff to life.

Breads were classified, at the highest levels, as one of 2 types. "Plain Breads", which were the common breads and to be sold in regulated sizes and/or prices and "Fancy Breads", where the baker was exempt and free to do what he wished and sell how he pleased.

You got "plain bread" in England as well as in Scotland. Plain bread was not a Scottish thing. But the breads themselves that were sold as "plain" were not the same, and there was a distinctly Scottish bread that came to dominate the plain scene in Scotland.

There were 2 main reasons for this. Firstly, Scottish wheat is by and large not that suitable for bread so in Scotland, oven-baked bread (not girdle/griddle breads) made much more use of imported, higher-gluten flours.

Secondly, Scottish bakers had a different baking practice for historical reasons. They used a very long-fermentation process (14-16 or more hours), meaning that nobody had to come in overnight to work the dough.

This also meant that they could avoid working on the Sabbath. Monday morning's bread started out on Saturday night and was then left to its own devices on the day of rest. As such they needed very different processes to England, and the end results were different.

As the 19th century progressed, the traditional methods in Scotland persisted - but were industrialised. Scottish bakers developed a batch-baking technique whereby loaves of high-gluten imported wheat were baked together in a large iron box (📷Mitchell Library C770)

These loaves were leavened not with baker's yeast, but with the traditional "barm" (a yeasty liquid from the brewing industry), and had the traditional long fermenting time.

The loafs stuck to eachother in the box, and were pulled apart after baking. Therefore on the top and bottom had an appreciable crust, apart from the "ender" loaves whose sides touched the edge of the box

https://twitter.com/christiebakery/status/982589318995771393

This picture from @weloveSY shows traditional plain loaves as baked in the famous Stag's bakery, before pulling them apart.

This form of industrialised baking produced a cheap, soft and tasty bread, without a hard, crunchy crust, in large quantities using aspects of the Scottish baking tradition. But it was susceptible to drying out quickly as there is a limited protective crust.

So that was what Scottish plain bread is and was, and why it was different from English plain bread - which could be any one of a variety of regional, mass-produced breads, with a totally different technique and ingredients.

Plain bread dominated the Scottish market. It came to account for 75% of *all* bread produced in Scotland, and in Glasgow as much as 90%. It was produced both by small, independent bakers, the Co-operatives and the big bread factories like Bilslands. flickr.com/photos/billiel…

In the late 19th century, the Scottish Plain was mainly known as the "plain loaf" but also as the "batch loaf" or "Scottish square" (but not "Lorne loaf").

This is where politics now starts to get involved. Back to those Bread Acts... To protect the public from being short changed by the baker, plain breads had to be sold only in avoirdupois units (pounds), and in multiples of 2 or 4 lbs. - the half-quartern and quartern loafs.

And plain bread *had to*, by law and on pain of some pretty hefty fines, be stamped or embossed with the weight. The Scottish batch system meant that the weight could not be embossed on the baking box, so they would have to be marked on afterwards.

This brings us to the "other" type of bread, "Fancy bread". Fancy bread was *all* bread that wasn't plain bread. For many years, it was the "Jenny Lind" (centre) that was popular in Scotland - probably a reference to the hair of the famous "Swedish nightingale"

But you could also get "French", "Viennese", "Belgian", breads, amogst others. But those were just names to sell the bread, nearly all Scottish bakers used exactly the same dough for all their fancy breads, so no matter what they called it you basically had the same bread.

Most bakers would make plain bread and just 1 or 2 styles of "Fancy" breads. The latter did not have to be marked in set weights.

But the custom in Scotland was that the fancy and plain loafs were generally sold at the same price, and the baker made the fancy loaves smaller to account for their higher production costs (they were much less efficient to produce).

In England they generally kept the weights the same between plain and fancy breads and varied the price instead. 🏴🍞

In England, the predominant style of industrialised Victorian plain bread was the "pan loaf", that is loaves baked in individual baking pans, such as the classic Hovis pan. These would be embossed with weights

But in Scotland, the pan loaf was considered to be a "fancy loaf", as it was economically more expensive to produce than the plain/batch/square loaf. And this is where Scottish bakers first found themselves falling foul of the bread laws.

You see the in 1892, the Burgh Police (Scotland) Act consolidated many existing municipal laws into one, including those on weights and measures concerning bread (how the Bread Acts were enforced in practice)

Notice that the relevant section (427) did not actually determine in any way what constituted "plain" or "fancy" breads. It just differentiated the two. More on that soon.

As mentioned before, the practice was for bakeries to sell a "plain loaf" in 2lb or 4lb sizes, marked as such in accordance with the law, and a few (or even just 1) "fancy" bread. These were once "Jenny Lind" loafs, but in the 1890s were predominantly becoming pan loafs.

Pan bread was sold at the same price at the bakery as the plain bread, but was less in weight (as it didn't fall within weight regulations), so people considered it to be a more expensive product as you got less for your money.

The pan loaf - what in England was the staple "plain" bread - became associated in Scotland with having a little bit more to spend, with acting "above your station". The phrase "pan loaf" became associated with being "well spoken", a sort of Scottish RP.

And in the legendary song, the distinction is noted;

"If it's butter, cheese or jeely, if the breid is plain or pan,

The odds against it reaching earth and ninety-nine to one." (sung in the Glasgow accent, "one" becomes "wan" to rhyme with "pan")

"If it's butter, cheese or jeely, if the breid is plain or pan,

The odds against it reaching earth and ninety-nine to one." (sung in the Glasgow accent, "one" becomes "wan" to rhyme with "pan")

(Although I think in Matt McGinn's version he actually sings "plain or bran" in some of the verses - i.e. plain or brown. I also seem to remember that it's Billy Connolly playing banjo on that recording, but I might have made it up)

Anyway, back to the all important Burgh Police Scotland (Act) of 1892. This consolidated the powers of weights and measures in the hands of the Burgh authorities (i.e. the city corporation in Glasgow or Edinburgh) and they set about enforcing it with some enthusiasm.

The city corporations in particular were quite determined to make sure that the customer was not being diddled by the baker, and that the regulated "plain" loafs were being sold in the correct 2lb or 4lb sizes only.

The inspectors found that the nominally 2lb plain loaf was varying in size from anywhere between 1lb 6oz to 2lb and therefore it was decided to make examples of those found flouting the regulations, in order to improve consumer confidence at a time of numerous food scandals.

In particular they began to crack down on the sale of pan loaves without the legally required weight stamp on them - the inspectors considered pan loaves to be "plain bread" under the terms of the 1892 act.

In 1898, the "Northern Baking Co." of Tradeston was taken to court for selling 50 "rumpy" loaves - considered a standard plain bread in England - without the weight stamp. The baker contended it was fancy bread and didn't need stamped or to be exactly 2lb.

Things came to a head in November of that year, when Peter Dick of Montgomery Street and Union Place in Edinburgh was prosecuted for selling 12 pan loafs not stamped with the imperial weight.

Superintendent Moyes of the City Weights & Measures department contended that pan loafs were plain bread, as they were considered as such in England, and as the baker conceded, they used exactly the same bread mixture as the plain loaves, therefore surely were also plain bread?

The baker contended that it was well known in Scotland that pan loafs were fancy bread and had always been sold as such, and customers knew this, therefore did not need to weigh 2lbs and did not need a weight stamp. Even if they used exactly the same dough.

The defence called witnesses from the Master Bakers incorporations of Partick, Dundee, Edinburgh and other towns, who all corroborated that in Scotland a pan loaf was a fancy bread, and always had been.

Sherriff Maconochie, presiding, determined that because the Burgh Police (Scotland) Act gave "no indication at all of what fancy bread was" that the only grounds he could therefore decide on was what was "ordinarily sold to and spoken by of the public".

Maconochie came down on the side of the bakers and therefore on 14th November 1898, the legal precedent was set in Scotland that a pan loaf counted as "fancy bread" and therefore by extension, the only bread that could legally be considered "plain bread" was the plain batch loaf.

Pan loaves were therefore exempt from having to be sold in 2lb or 4lb weights, and need not be stamped as such, and bakers were free to continue to sell them at the same price as their plain loaves, but slightly smaller sized, as they contended they had always done.

This had the knock-on effect of making Scottish pan loaves smaller than their English counterparts. In England, they remained as being 2lb, in Scotland they dropped to 1lb 12oz (1.75lb), so bakers could continue to be sell them at the same price as their plain loaves.

Now that what was plain breid had been decided in law, the populace of Scotland got back to their lives, consuming large quantities of the substance as the basis of their diet. As mentioned earlier, 90% of bread in Glasgow as the plain loaf and it was 75% overall in the country.

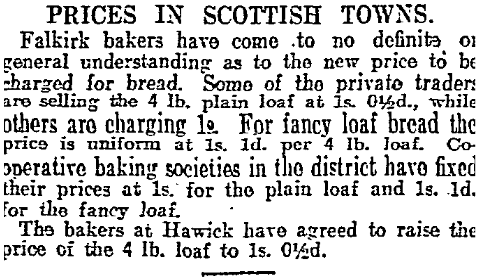

Prices varied by burgh, being determined by the local incorporation of Master Bakers, with small variations up or down to accommodate for competition or local factors like transport or fuel costs.

So long as Scotland could get a good, affordable supply of the higher quality, high gluten, white flour needed to produce the plain loaf, there wouldn't be a problem.

And that flour had to come across the Atlantic from Canada and America. No problem in times of peace and rapidly improving transatlantic shipping. But then something came along that interrupted that vital flour supply - the world went to war in 1914.

By early 1917, the U-boat war in the North Atlantic was biting hard, and the supply of food to the UK from the breadbaskets of Canada and America were perilously threatened. The government had to act.

In May 1917, the Minister for Food warned the cabinet that by September, it would be a "difficult problem" to feed the nation.

Firstly, *all* loaves, whether they be plain, pan or fancy, were standardised as either 2lb or 4lb. In England, a lot of bread was still sold by a standard price and not a standard weight, this was changed to standard weight.

Secondly, the sale of fresh bread was banned. All bread had to be aged at least 12 hours before sale. This was to ensure *all* bread was stale at point of sale, so people wouldn't refuse to by stale bread today over fresh bread tomorrow, cutting down waste.

Stale bread was felt to be more healthy, and easier to slice thinner, so you could get more slices out of a loaf. More importantly it meant that overnight baking could be stopped, saving the costs and fuel of lighting the industrial bakeries.

And people just consumed less of it. It's much less tempting to overindulge on stale bread, vs. gorging on a warm loaf not long out the oven. It was found this alone reduced bread consumption by 5%, saving on wheat imports.

Thirdly, commercial bakers were obliged to use a standardised flour, to produce a "regulation bread". "Standard Flour" had the extraction rate raised from the 70% of white flour (meaning 30% of the grain is not milled, discarded as bran and husk) to 81%. 100% would be wholemeal.

The regulation flour was also compulsorily adulterated with the flours of non-wheat grains. Maize, potato, barley, oat etc. Legally at least 10% had to be non-wheat flour, and millers at their own discretion could use up to 25%.

Not surprisingly, this caused problems in Scotland. Scottish bakers had to use 2lb or 4lb English bread pans, rather than the favoured 1lb 12oz pans, resulting in bigger loaves. They couldn't sell it at the same price as plain loaves, and consumption of "fancy" pan bread fell 33%

A far bigger problem was with the flour. Scottish plain loaves needed high-gluten flour, and the high-extraction, adulterated flour of WW1 just did not work properly. Millers did not have to specify the level or type of adulteration either, so each batch of flour was different.

So bakers found themselves having to experiment with each new batch of flour until they could alter their process to suit the new flour mix - which inevitably changed in the next batch. They begged the government to mandate millers specify the flour contents.

The problem was so severe in 1917 that it was genuinely a cause for concern that the Scottish plain loaf would have to be abolished, and people would have to start eating English-style pan bread!

A further problem was that given the higher levels of extraction from the wheat grain, flour was more at risk of "rope". Rope, or Bacillus subtilis, is a bacteria whose spores live in the soil and can infect wheat.

Rope spores can survive baking temperatures, and the moist, warm interior of freshly baked bread is perfect for them to replicate, feasting off the contents of the loaf. Bread infected with rope has a distinct taste, variously described as silagey or pineappley or vomity.

Rope bread was barely edible and bad bread was said to be "a bit ropey". This is the origin of the English language idiom of something of dubious quality being "a bit ropey". Poor farm and mill hygiene in wartime and increased grain extraction cause an epidemic of ropey bread.

The wartime bread acts, which lasted from 1917-1920 caused a big shift in Scotland away from pan and fancy breads, to the cheaper plain loaves, at the same time as the quality, economy and palatability of those plain loaves decreased dramatically.

The law intervened in 1918, and a follow up Bread Order determined that as in Scotland the pan loaf was legally a "fancy" loaf, Scottish bakers could get an exemption and go back to selling it at 1.75lb sizes so that its cost could be the same as plain bread.

If you thought (or hoped!) that was the end of the legal history of plain bread in Scotland, then I'm sorry there are the events of 1926 and 1942 to get through... stay tuned!

This thread has turned out to be - by necessity - a bit of a monster. And we're not yet finished... Sorry!

With the WW1 Bread Acts, the government didn't just meddle with bread production to reduce consumption of bread and flour, it also subsidised bread to stop price inflation, by guaranteeing bakers a fixed price per sack of flour and paying the millers the difference.

The price of plain bread (be it English or Scottish or Welsh or Irish style) was set at 9d per quartern (4lb) loaf. So even if the bread was rubbish, and you were encouraged to eat less of it, you could still afford to.

For fancy bread, the bakers could charge cost + profit, so although in England the price of pan bread was fixed and subsidised at 9d (because it was "plain"), in Scotland it was classed as "fancy" bread so even with the loaf size reduced to 1.75lb it became unaffordable for many.

Although the war ended in 1918, price and bread controls did not, until April 1920 when the various Bread Act restrictions were finally ended. The government still controlled the price of flour, but was not subsidising it to guarantee a 9d plain loaf

This caused great anxiety, as with the price cap on flour lifted, inflation (particularly post-war wage and fuel inflation) would catch up with the price of a staple loaf of plain bread and huge price rises were feared.

Previous wartime price increases had been capped at 1/2d per 4lb loaf before stabilising at 9d, but the rise in the price of a sack of flour meant it was going to increase by 2 1/2d or 3d in one go - 5 to 6 times more than before.

The Scotsman reported that such a price increase was "unprecedented in the history of the trade". It warned the public to expect bread to increase in price from 9d to 1s 1d - 1s 2d (4d - 5d) in coming weeks - or 45-55%.

When restrictions ended on April 12th 1920, the price of bread did indeed jump - but not by quite that much. Prices were agreed and set locally by Incorporations and Associations of Master Bakers, accounting for local costs like fuel and transport and local wage negotiation.

Outside of the cities, the prices were higher, driven by transport costs. In Buckie, the price did hit 1s 2d per quartern loaf, causing local outrage. Housewives in one section of the town took mass civil action and refused to accept the morning rolls, sending them all back.

And again the legal question over what constituted fancy bread in Scotland raised its head. The authorities in Dunblane tried to prosecute two bakers, member of the Scottish Association of Master Bakers, for selling pan loaves that were under weight (i.e. less than 2lb)

The Procurator Fiscal refused to support the prosecution, and instructed the Crown not to proceed. Once again, the might of the Scottish legal establishment had ruled that pan loaves were fancy bread.

The government recognised that returning bread to the free market had undesirable and unforeseen effects on affordability, and as early as 1922 they were looking at reintroducing control with a Sale of Bread Bill

The Sale of Bread Bill wanted to re-introduce the sale of *all* bread (fancy or plain) by weight rather than price. In Scotland it was the custom to sell fancy bread by price and in England this was often the case for plain bread

Sale by price means that you asked for a specific price of loaf (e.g. 1s) and the baker sold you a loaf that they had baked to that price point. Its weight would vary with the price of flour, labour etc., but the cost stayed the same.

Such loaves kept bread affordable, but suffered from Shrinkflation in that the bakers simply reduced the size of the loafs to account for inflation of ingredient, fuel and labour costs. Bread got smaller but the price stayed the same.

This Bill also wanted to fix the weight of *all* pan loaves at 2lb or 4lb, including those in Scotland that were classed as fancy bread and were sold in 1.75lb weights. This rattled the Scottish bakers, who remembered what happened the last time they had to do this in 1917.

The Scottish local authorities supported the classification of pan bread as plain bread, as they felt bakers were using its classification as fancy bread to rip off customers with underweight loaves.

In Glasgow, the Chief Inspector of Weights & Measures reported his department had made in the year 484 inspections, measuring 3,076 loaves at 47 different bakeries. The weights of plain loaves were found to be "satisfactory", but pan loaves "most unsatisfactory".

There were numerous delays to the progress of the Bill, and it rumbled on in parliamentary purgatory for almost 4 years. The Scottish Association of Master Bakers were vigorous in their defence and found support for their cause with the Earl of Elgin in the Lords (📷NPG)

Elgin spoke up for the SAMB in the Lords, and pushed their amendment that in Scotland a pan loaf would be sold in 1.75lb weights, would still be a "fancy" bread but offering the concession that they would stamp the weight on the baking tins.

The bakers contended that in Scotland they were not equipped for the mass production of 2lb and 4lb pan loaves, and that it would be uneconomic to produce them vs. 2lb and 4lb plain loaves without the wartime subsidies. The bakers were supported by the Cooperatives.

Debating the "problem of the Fancy Loaf" in the Lords, Elgin went on the record to say that the Scottish plain loaf was "the national loaf", "was of vital importance to Scotland" and the bill as it stood was "an injustice to Scotland".

Following Elgin's intervention it was finally agreed at the end of July that in Scotland, the pan loaf was exempted from being 2lb or 4lb, and could be sold in 1.75lb sizes so long as it was clearly marked. Curiously, 1.75lb is ~800g, the size of a standard modern loaf...

This came too late for baker George Walker of Coldstream, who in April had been charged with selling bread "deficient in weight and failing to carry scales". He had gone to sell bread in nearby English villages where his pan loaves became plain as soon as he crossed the border.

His "but in Scotland" defence of pan being fancy bread carried no weight with the English magistrates and he was fined £1 for failing to carry scales and £5 for selling pan bread deficient in weight.

The bill passed as the Sale of Food (Weights and Measures) Act 1926 and people once again got back to their lives and eating their plain bread (📷Farmersgirlkitchen)

Plain bread returned to the Scottish news agenda in 1934, when poor wheat crops in America pushed up the flour price and the price of a 4lb plain loaf in Aberdeen to 9½d - meaning the standard 2lb loaf was 4¾d. A supply of farthings had to be sent to the Granite city to cope.

The final chapter (phew!) in the plain bread story takes us to WW2. Once again the government guaranteed the price and supply of flour, and again mandated increased extraction by millers from the grain. The "National Wheatmeal" was 85% extraction (70% = white, 100% = wholemeal)

The higher extraction of wheat than in WW1 (which was 81%) was possible with better milling technology, and meant that there was no debasing of the flour with potato starch or other grains.

Once again, the government also launched campaigns to reduce bread consumption, but didn't force stale bread on people like they had in WW1

You may be familiar with the concept of the WW2 "national loaf." This was not a standard type of bread - it was any "plain bread" baked with the "national wheatmeal flour", so in Scotland it was a "Scottish plain" loaf baked in a box, in England a pan loaf, etc.

A problem arose in Scotland in 1942 when it was found that there was excessive bread wastage when compared to England. Bakers were baking bread, but not all of it was selling, and too much was going stale (a Scottish plain loaf goes stale quicker) and being sent for pig food

Such was the issue, that Lord Woolton (of Pie), the Minister of Food, was sent to Scotland to investigate and find a solution.

What Woolton found was that picky Scottish housewives were refusing to buy the "sider" and "ender" loaves - that is those at the side and end of the baking box with a side and end crust from contact with the hot metal in the oven. (📷Christie the Baker)

This was a peculiarly Scottish issue, not the case with English pan loaves. Woolton appealed directly to the customer; "I appeal to Scottish housewives to take their bread as it comes. Waste of bread means waste of lives".

Woolton had a point - wheat had to come across the Atlantic from America and Canada and ships were being sunk and lives lost doing this at a terrible and unsustainable rate. It was estimated as much as 5% of Scottish plain bread production was being wasted.

The national importance of the plain loaf was recognised, and even though pan loaves were better with the "national wheatmeal flour", they were less efficient to produce. The prospect of selling the sider and ender loaves at a discount (they were often mis-shapen) was entertained

It was noted that the loaf was of vital important for "workmen's sandwiches" - A Scottish miner or workie would go nowhere without his "piece tin", specially shaped to accommodate the tall slices of a plain loaf.

https://twitter.com/NatMiningMuseum/status/1317027503651737600?s=20&t=UPb4dLxuSZdbYDAd1vSU5w

Woolton's appeal obviously had the desired effect, as the issue did not reappear in the news agenda after May 1942. And so the populace of Scotland got on with eating (or enduring) their national plain loaves, be they sider loaves or ender loaves or otherwise.

The "plain bread thread", all glorious 109 tweets of it... as 1 easier to read page. 🧵➡️📄 threadreaderapp.com/thread/1553062…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh