100 years ago today the most intensive day of fighting in the Battle for Cork was taking place around Rochestown. To mark the anniversary of the bloodiest engagement of Cork's revolutionary period, this🧵explores some of the archaeological traces left behind. #BattleforCork100 /1

The National Army had landed in Passage West the previous day, moving to engage IRA defenders on the high ground to the west. Some of the very first fire of this engagement can be traced today- these are impact scars from National Army bullets on buildings opposite the docks. /2

The IRA defence was aided by fire from Carrigaloe across the Lee Channel on Great Island. Fire from buildings here directed at the National Army landing force smacked into buildings in Passage West, especially those on higher ground. Here are impacts in Passage from that fire. /3

The National Army responded to the IRA engaging them from across the river channel by peppering the buildings on the opposite side with rifle and machine-gun bullets. The buildings in Carrigaloe on Great Island still bear the evidence of that response. /4

The National Army soon drove the small number of IRA defenders of Passage West out of the town towards Cork. Today many of the locations photographed at the time by W.D. Hogan (now in @NLIreland) are instantly recognisable when comparing them to the modern landscape. /5

The IRA retreat from Passage was far from the end of the fighting. In order to halt the National Army advance to Cork City, road and rail bridges were blown. The damage to the road bridge can still be seen at Brendan Barry Murphy Park in Rochestown, traceable in later repairs. /6

The 9 August saw the focus of the fighting shift to Rochestown, and it was the bloodiest day of the battle. The Capuchin Friary there had visits from IRA defenders during the night of the 8-9, some receiving absolution before the heavy engagement they knew was coming. /7

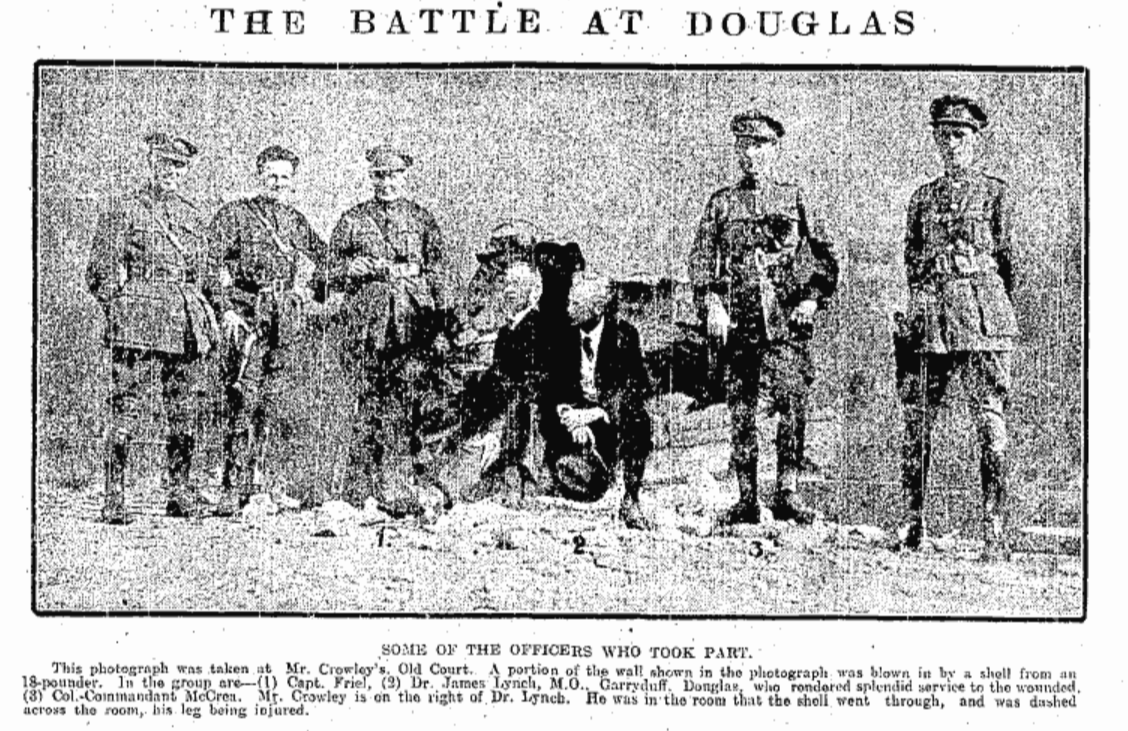

Holding buildings and hedgelines around Rochestown, the IRA were engaged by both National Army infantry and artillery, in the shape of an 18 Pounder Field Gun (positioned near the Friary). Among the buildings damaged was Old Court House, where a shell pierced the wall. /8

Pushed out from Rochestown proper, the epicentre of the fighting shifted to around the modern Garryduff Sports Centre, where National Army troops sought to push through strong IRA positions centred on machine-guns set up on field boundaries, including this one in Moneygurney. /9

The home of Dr James Lynch at Garryduff came under intense IRA fire, aimed at National Army troops in and around it, who quickly began to fall victim to the bullets. The home itself became an impromptu dressing station as the family sheltered within. /10

In some of heaviest fighting seen in the Civil War, the National Army troops- many WW1 veterans- had to push up this hill through the fields and into a storm of machine-gun fire, causing many casualties. For some, it must have felt like being back on the Western Front. /11

Near the top of the hill, close to where three National Army soldiers were cut down, a lone gate still bears testimony to the savage fighting. Known locally as the "Battlefield Gate", it retains a number of bullet-holes created during the 9 August 1922 fighting. /12

Numbers finally began to tell, and the IRA were forced back. Not all left. A "last stand" at Cronin's Cottage cost the lives of two IRA defenders, including the well-liked Scot Ian "Scottie" MacKenzie Kennedy. The Cronins were later photographed outside their devastated home. /13

The fighting continued for a third day, as the National Army pushed into Douglas village. But ultimately the IRA were forced to withdraw, the City of Cork fell, and the fighting moved west. Less than two weeks later, Michael Collins would lose his life at Béal na Bláth. /14

We have created a map of many of the archaeological features associated with the first two days fighting in the Battle of Cork (below). You can check it out in more detail at the Landscapes of Revolution page dedicated to it here: landscapesofrevolution.com/projects/battl… /15

You can also read more about the archaeology of the Battle for Cork in the @RTE & @UCC hosted piece, "Bullet Holes & Battlefields: The Archaeology of the Battle for Cork" (and thanks to @heleneokeeffe for the invitation to contribute!) rte.ie/history/conven… /16

There is a also a piece Professor Joanna Brück of @UCDArchaeology and I wrote on the archaeology of the battle for @DGannon2016 & @FFearghal's excellent @RIAdawson book "Ireland 1922: Independence, Partition, Civil War" ria.ie/ireland-1922-i…. /17

The analysis on which the work was based was undertaken by Professor Brück and I together with Dr John Borgonovo and @niallmurray1, both of @UCCHistory. You can find out more about the archaeological traces of Ireland's revolutionary past at landscapesofrevolution.com /18 🧵ends.

And I should add, the work of the Landscapes of Revolution Project is continuing under the excellent guiding hand of @AbartaGuides - you can explore their current project on the Tipperary IRA Map here: landscapesofrevolution.com/tipperary-ira-… (🧵really ends now, I promise 😀)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh