Diffusion models like #DALLE and #StableDiffusion are state of the art for image generation, yet our understanding of them is in its infancy. This thread introduces the basics of how diffusion models work, how we understand them, and why I think this understanding is broken.🧵

Diffusion models are powerful image generators, but they are built on two simple components: a function that degrades images by adding Gaussian noise, and a simple image restoration network for removing this noise.

We create training data for the restoration network by adding Gaussian noise to clean images. The model accepts a noisy image as input and spits out a cleaned image. We train by minimizing a loss that measures the L1 difference between the original image and the denoised output.

These denoising nets are quite powerful. In fact, they are so powerful that we can hand them an array of pure noise and they will restore it to an image. Every time we hand it a different noise array, we get back a different image. And there we have it - an image generator!

Err….well…sort of. You may have noticed that this generator doesn't work so well. The image looks really blurry and has no details. This behavior is expected though because the L1 loss function is bad for severe denoising. Here's why...

When a model is trained with severe noise, it can’t tell exactly where edges should be in an image. If it puts an edge in the wrong place, it will incur a large loss. For this reason, it minimizes the loss by smoothing over ambiguous object boundaries and removing fine details.

Of course the severity of this over-smoothing depends on how noisy the training data is. A model trained on mild-noise images like this one can accurately tell where object edges are located. It learns to minimize the loss by restoring sharp edges rather than blurring them out.

So how can we generate good images? First, use a severe noise model to convert pure noise to a blurry image. Then feed this blurry image to a mild-noise model that outputs sharp images. The mild-noise model expects noisy inputs though, so we add noise to the blurry image first.

Here's the process in detail: The denoiser converts pure noise to a blurry image. We then add some noise back to this image, and feed it to a model trained with lower noise levels, which creates a less blurry image. Add some noise back, and denoise again...and again.

We repeat this process using progressively lower noise levels until the noise is zero. We now have a refined output image with sharp edges and features. This iteration process escapes the limitations of the Lp-norm loss on which our models were trained.

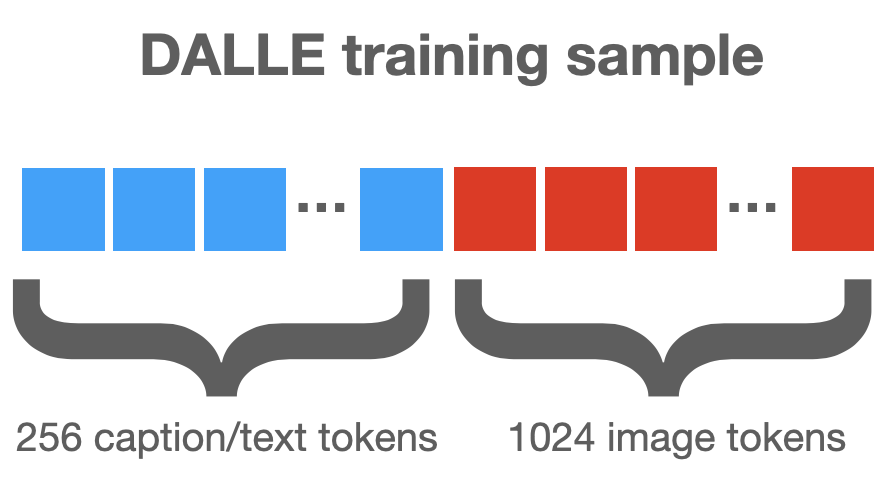

What about those fancy models that make images from text descriptions, like DALLE and GLIDE and Stable Diffusion? These use similar denoising models, but with two inputs. At train time, a clean image is degraded and handed to the denoising model for training, just like usual.

At the same time, a caption describing the image is pushed through a language model and converted to embedded features, which are then provided as an additional input to the denoiser. Training and generation proceed just like before, but with text inputs providing hints.

Theoreticians understand diffusion as a method for using noise to explore an image distribution. The denoising step can be interpreted as a method for taking a noisy image and moving it closer to the natural image manifold using gradient ascent on the image density function.

When these denoising steps are alternated with steps that add noise, we get a classical process called Langevin Diffusion in which iterates bounce around the image distribution. When this process runs for long enough, the iterates behave like samples from the true distribution.

So why is this understanding broken? Existing theories of diffusion rely strongly on properties of Gaussian noise. They also require a source of randomness in the image generator that slowly sweeps from a “hot” noisy phase to a “cold” deterministic phase.

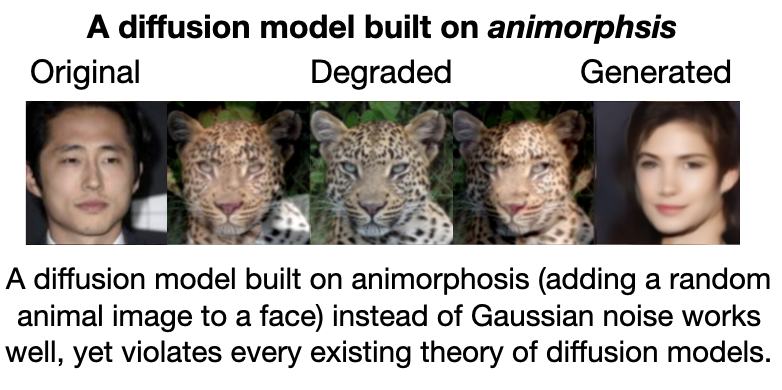

However, my lab has recently observed that generative models can be built from any image degradation, not just noise. Here's an example in which images are degraded using heavy synthetic snow (from ImageNet-C). By iteratively removing and adding snow, we can restore the image.

Snow and animorphosis (above) are fun curiosities, but in practice we might want diffusion processes for inverting real-world image degradations, like blur, pixelation, desaturation, etc. By swapping noise with arbitrary transforms, we get diffusions that invert almost anything.

These generalized diffusions work great, and yet they violate every existing theory of diffusion, all of which rely strongly on the use of Gaussian noise. Some of these are even “cold” diffusions that require no source of randomness at all.

arxiv.org/abs/2208.09392

arxiv.org/abs/2208.09392

Appendix: If you want to learn more, here’s a reading list that covers diffusion topics.

Iterative denoising processes for image generation:

arxiv.org/abs/2010.02502 (DDIM)

arxiv.org/abs/2006.11239 (DDPM)

arxiv.org/abs/2009.05475 (Score Matching)

Iterative denoising processes for image generation:

arxiv.org/abs/2010.02502 (DDIM)

arxiv.org/abs/2006.11239 (DDPM)

arxiv.org/abs/2009.05475 (Score Matching)

arxiv.org/abs/2102.09672 (Improved DDPM)

arxiv.org/abs/2201.11793 (Image restoration)

Neural architectures for diffusion:

arxiv.org/abs/2105.05233

arxiv.org/abs/2201.11793 (Image restoration)

Neural architectures for diffusion:

arxiv.org/abs/2105.05233

Text to image models:

arxiv.org/abs/2207.12598 (Classifier-free guidance)

arxiv.org/pdf/2112.10741… (The GLIDE model)

arxiv.org/abs/2112.10752 (Latent diffusion models)

arxiv.org/abs/2207.12598 (Classifier-free guidance)

arxiv.org/pdf/2112.10741… (The GLIDE model)

arxiv.org/abs/2112.10752 (Latent diffusion models)

Theoretical foundations:

arxiv.org/abs/1503.03585 (Original paper by Sohl-Dickstein et al)

arxiv.org/abs/2011.13456 (Score-based models)

arxiv.org/abs/1907.05600 (Gradients of data distributions)

arxiv.org/abs/1503.03585 (Original paper by Sohl-Dickstein et al)

arxiv.org/abs/2011.13456 (Score-based models)

arxiv.org/abs/1907.05600 (Gradients of data distributions)

Finally, thanks a bunch to @arpitbansal297

@EBorgnia, Hong-Min Chu, Jie Li, @hamid_kazemi22, @furongh, @micahgoldblum, and @jonasgeiping!

@EBorgnia, Hong-Min Chu, Jie Li, @hamid_kazemi22, @furongh, @micahgoldblum, and @jonasgeiping!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh