There are few words that will get some Scottish folk as misty eyed, nostalgic and feeling wistful as "Creamola Foam".

But what is this apocryphal delicacy? How and where did it come to be? And just what is its dark secret? Add 2 spoons, stir, and let's find out. 🧵👇

But what is this apocryphal delicacy? How and where did it come to be? And just what is its dark secret? Add 2 spoons, stir, and let's find out. 🧵👇

Creamola Foam is a fairly simple and entirely chemical concoction that was sold widely in Scotland and hasn't been available since Nestle cancelled it in 1998. 🥄Mix 2 teaspoons of its crystals with water and you've got yourself a satisfyingly synthetic fizzy, foamy drink.🥄

It is a blend of fruit acids with bicarbonate of soda, which react in water to produce the fizz; saponin as a foaming agent, giving it a beery head; gum Acacia or Arabic thicken it; sugar and saccharin sweeten it; and chemical flavours and colours flavour it and colour it.

Creamola Foam was unleashed on the Scottish public in May 1932 at the Ideal Homes and Foods Exhibition in the Kittybrewster Olympia Hall in Aberdeen.

📰"Those who try [it] will appreciate this delicious, wholesome refreshment" said the visiting reviewer from the Press & Journal.

📰"Those who try [it] will appreciate this delicious, wholesome refreshment" said the visiting reviewer from the Press & Journal.

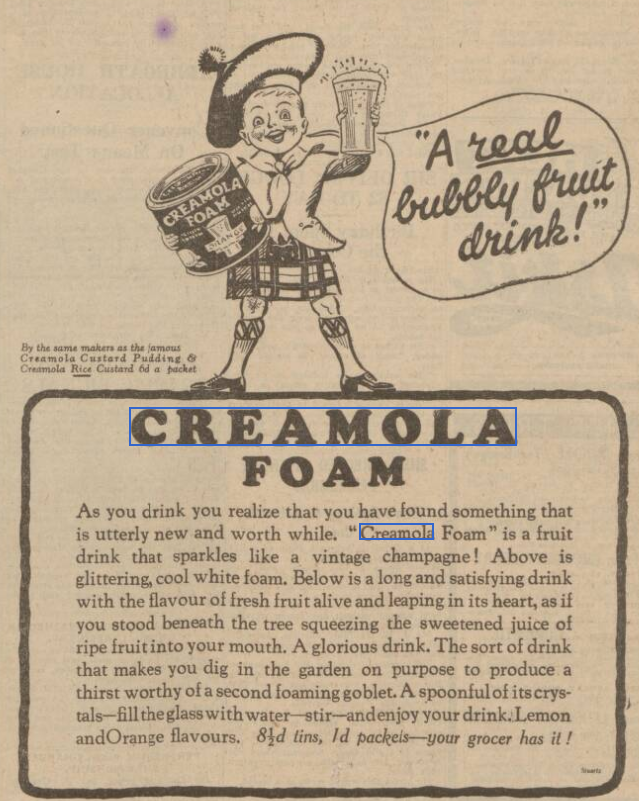

Initially available in two flavours; lemon and orange, lime and then ginger were soon added to the lineup. The manufacturers - Creamola Food Products - were already a household name but went heavy on the advertising and it was a runaway success.

The Creamola mascot - a kilted, rosy cheeked boy with an oversize bunnet and a neckerchief - featured in the newspaper campaigns. The drink was compared to sparkling like "a vintage champagne", with "glittering, cool white foam" and as providing "a long and satisfying drink"

But don't believe the advertisers "with the flavour of fresh fruit alive and leaping in its heart, as if you stood beneath the tree squeezing the sweetened juice of ripe fruit into your mouth" schtick. This "glorious", "real fruit" drink was nothing but chemistry in a glass.

Creamola Foam wasn't just for the masses though, Creamola's advertising in the late 1930s has a real middle class, interwar aspirational vibe to it - himself sits around in his 3 piece suit while his elegant, befrocked wife serves him up refreshing glasses of Foam.

Creamola Foam was "Refreshing as a sea breeze" (which, in this country usually means it is violent, intensely salty and will strip the paint off of a car) old

Creamola Foam wasn't rationed during WW2, but generally just wasn't available as the country had better uses for its ingredients than a novelty drink. It was relaunched post-war with a change of flavours and a new formula that dialled back the effervescence; "Foams Without Fizz".

Creamola was bought by Rowntrees in 1966. Attempts to popularise it in England were tried and failed, but it retained a soft spot in Scottish hearts, minds and stomachs and production of this industrial refreshment continued.

The formulation changed again in the 1980s to return it to being a much fizzier drink truer to the original and it remained this way with more modern foaming and thickening agents up until this niche, provincial product was cancelled by the Swiss bean counters at Nestlé 🇨🇭

So who made Creamola Foam? And where?

Well that was Creamola Food Products Ltd. of Glasgow, a household name in Scotland and beyond in the first half of the 20th century. From the 1930s their factory was in the Plantation district (more on that appropriateness later)

Well that was Creamola Food Products Ltd. of Glasgow, a household name in Scotland and beyond in the first half of the 20th century. From the 1930s their factory was in the Plantation district (more on that appropriateness later)

Creamola built a huge range of popular, brand-name household products around the simple concept of packet of a starch thickener and/or setting agent with sweetening, flavouring and colouring that could be made at home into a wide range of desserts and puddings (📷Mike Ashworth)

Rice, wheat, cornflour, sago, tapioca, gelatine, arrowroot. You name it, if it would set or thicken, Creamola would packet it and sell it to you as a tasty treat. The company were heavy advertisers, and claimed to "tickle the World's Palate"(📷University of Glasgow)

This 1929 colourised photo of a Dumbiedykes gable end in Arthur Street has a poster for their principal product - Creamola Custard - in the centre. It is has a personal touch for me as my Mum's family lived in the tenement to the left in the 1910s (📷Edinburgh City Libraries)

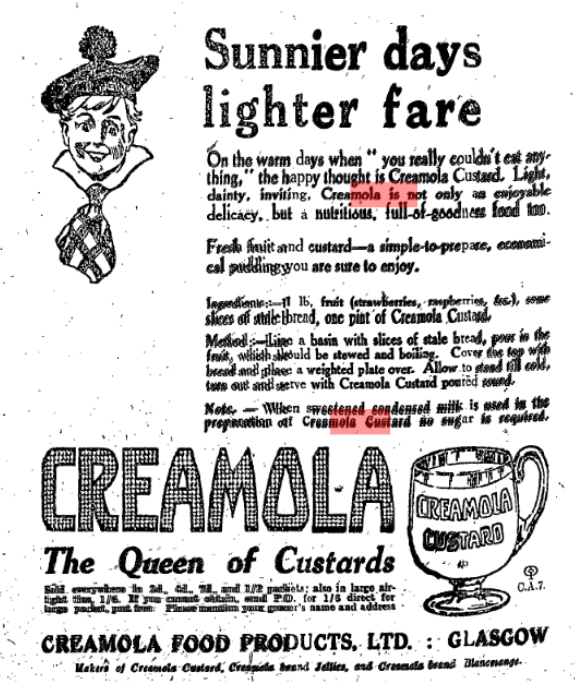

Creamola kept their products constantly in the newspapers in the 1920s and 30s, pushing themselves relentlessly as "The Queen of Custards" and giving serving suggestions and recipes such as apple trifle and fruit pudding.

Creamola Food Products came into being on December 29 1919 when the Glasgow company of D. K. Porter & Co. was incorporated as a limited company. They took the name of their principal product, itself borrowed off a defunct Victorian brand; "the cream of toilet soaps".

D. K. Porter was an established importer of arrowroot - a food thickener, popular with the Victorian dietetic and invalid food movements. The switch to cheaper, cornstarch based-products was obvious, after all it was made just down the road in Paisley

https://twitter.com/cocteautriplets/status/1554506467407011840?s=20&t=X0jpShfabnbUUYTV2hdJPw

Porters launched Creamola in 1910 at the Ideal Home Exhibition, a "new preparation"; "a highly nourishing food, the nitrogenous or flesh forming material which it contains being enormously increased in comparison with is found in other farinaceous foods". Yes I've no idea either.

Success came quickly and when war came in 1914, they saw an opportunity and made sure their product was sent to our boys on the front by donating 70,000 tins to the Red Cross.

📰The papers declared, "All parcels now going to France should contain at least one tin of Creamola"

📰The papers declared, "All parcels now going to France should contain at least one tin of Creamola"

A smash hit at home too, Porters were quick to remind housewives that their products didn't require eggs so were "an incalculable advantage" to keeping children full of puddings during times of shortage. Note again that purposeful, middle class vibe to the advert.

By 1917, Porters were declaring in adverts "Youth *must* be served even in these days when food is scarce... and CREAMOLA is the ideal means of making up to the children with "growing" appetites for the meat shortage".

👩Sorry son, there's no beef but you can have custard.

👦Yay!

👩Sorry son, there's no beef but you can have custard.

👦Yay!

In 1918 the food situation was critical on the home front, but Porters were there with their ersatz puddings to feed the nation. "Let rations be what they will. Creamola Custard Pudding will ever make up the shortage"

Business boomed to the extend that Porters couldn't keep up with demand, and moved to a new factory on Great Clyde Street along the riverside. (📷Mitchell library)

To keep up with the public's insatiable appetite for custard puddings, the machinery was run 24/7 and Porters relentlessly strived to make the process more efficient by doing things like taking out air filters and not recycling spilled flour.

And this caused a problem, because next door to the Great Clyde Street factory was the chapel house of St. Andrew's R. C. Cathedral and they were greatly disturbed by the non-stop whirr and clatter of custard machinery, and the relentless film of white powder coating everything

Porters denied that they were causing a noise and dust nuisance and hoped that Archbishop Macguire would go away if they ignored him. But the Archbishop was not to be messed with, and Porters found themselves hauled infront of Lord Hunter at the Court of Session in a law suit.

An independent investigator found that the "clicking sound produced by the speed-reducing gears of the mixing machines and the tapping sound of the lever at the weighing machines" were indeed a nuisance to the Archbishop's peace

His Lordship concurred, and Porters were ordered to desist their night shifts and put the filters back on to keep the dust levels back down. Porters backed down, and were keen to advertise that they could keep up with demand by dayshifts alone.

By the end of that year, the Porter name was gone and it was Creamola Food Products above the door henceforth and we all lived happily ever after and that's the end of our story.

Or is it?

Or is it?

No, indeed it's not. I didn't get you this far not to go back even further.

So who were or was D. K. Porter? How did they get into the arrowroot game?

Tracing back the lineage before the Creamola days uncovers a surprising story with a dark secret at its heart.

So who were or was D. K. Porter? How did they get into the arrowroot game?

Tracing back the lineage before the Creamola days uncovers a surprising story with a dark secret at its heart.

The key to unravelling the D. K. Porter riddle is arrowroot, a South American and Caribbean staple foodstuff from whose roots can be extracted a starchy thickening agent. Gluten free, it was big in the Victorian dietetic and "invalid diet" movements. (📷CC-by-SA 2.5 Noblevmy)

As early as 1884, D. K. Porter are importing bulk arrowroot into Ayr from St. Vincent in the Caribbean for sale in the market at Kilmarnock. Over time the centre of economic gravity drags the trade inevitably to Glasgow.

We now follow the breadcrumb trail in the adverts of St. Vincent and the "Three Rivers Brand". Three Rivers it turns out is a plantation estate in St. Vincent, and who should own it but D. K. Porter & Co. of St. Vincent.

D. K. Porter are vertically integrated you see; they are not just the importer, but the exporter too. And also just happen to be the shipper.

D. K. Porter is a partnership between David Kennedy Porter, born in Riccarton, Ayrshire in 1820 and James Graham, a London-born Scot. Both emigrate to St. Vincent where Porter joins Graham in slowly building up a portfolio of sugar plantations.

Porter and Graham exploit two things. The emancipation of plantation slaves in St. Vincent in 1838 and the "Encumbered Estates Act" of 1856 which saw the forced sale of bankrupt estates.

Freed slaves find themselves pushed to marginal lands, and men like Porter and Graham buy up the bankrupt estates on the cheap and concentrate them into a few holdings, bringing in indentured labourers from India in the 1860s-1880s to work them

In 1829, St. Vincent had 98 separate sugar estates. By 1882, nearly all the cultivatable land was owned by just 5 landowners; D. K. Porter were the largest, owned 22 estates (nearly half) and fully 2/3 of all productive land on the island.

Graham died in 1877, having amassed an immense fortune of £250,000. Thomas Rennie Nairn took his place. David Kennedy Porter died in 1891, leaving £105,849. His place is taken by his nephew, also of Riccarton, Alexander Porter.

But despite having secured a stranglehold on St. Vincent and running a comfortable oligopoly on the back of the labour of others, D. K. Porter are in trouble. The price of sugar has crashed following the introduction of sugar beet in industrial quantities to Europe.

D. K. Porter had St. Vincent stitched up. They controlled the local legislature. They were "vehemently opposed to the introduction of central mills" which might have helped small proprietors and sharecroppers, and indeed were generally opposed to *any* improvements on the island

"It was the labouring population that suffered most from this selfish and parsimonious attitude concerning the improvement of St. Vincent". D. K. Porter would only do what was right for D. K. Porter.

D. K. Porter complained labourers were lazy, but reneged on wage payments and strictly controlled availability of work. They resented improvements or attempts to improve labour conditions. The campaigned against taxes to fund health provision for workers or finance public works.

Instead of working to innovate and improve efficiency of sugar production and the lot of their workers, Porters cast around instead for a new money-making scheme and hit on arrowroot. In the 1880s they ripped up nearly all their estates and planted instead the arrowroot plant

Arrowroot saved Porters. As sugar exports collapsed, they flooded the markets instead with arrowroot, halving the price of it in Europe and within 20 years St. Vincent would have an almost complete world monopoly on the stuff.

At the helm, Alexander Porter is described as being "unwilling to invest any of his profits in the improvement of either his estates or the island as a whole... an indication of his lack of commitment to the island's prosperity."

D. K. Porter would probably have been content to sit back and grow rich(er) off of arrowroot, but nature intervened. The island was devastated by floods in 1896, a hurricane in 1898 and finally in 1902 the volcano La Soufrière erupted.

Mount Pelée on nearby Martinique had an even more devastating eruption only hours later, killing 29,000. On St. Vincent, 1,680 died, 600 were seriously injured and 4,000 were homeless. "Not a single estate works .. escaped injury"

Up to this point, Alexander Porter had largely resisted outside Imperial government intervention by way of financed estate reform brought on by the natural disasters. But he dies in 1903 and leaves the business to his sons Donald Fraser and John Gemmel Porter.

His sons for a while maintain the father's mould, but soon decide to take the Government's money and sell the estates, the last is sold in 1909.

However they are also modernisers and realise the sensible money is not in sale of raw arrowroot, but in the processing of it and sale direct to consumers. At the Barbados Agricultural Show in 1904 they unveil "Three Rivers Brand" of pure arrowroot.

Porters try and shift the image of arrowroot from being a food for invalids to one of making easy deserts. In 1904 they are advertising it for sale in Glasgow, imported from St. Vincent. In Glasgow, William Galbraith Hetherington is put in charge (📷University of Glasgow)

Under the energetic, paternalistic leadership of W. G. Hetherington, D. K. Porter, rather "Three Rivers Arrowroot" begins to prosper in Glasgow, rapidly becoming a household brand.

It is Hetherington who gets D. K. Porter to incorporate as Creamola, and he remains at the helm until his death in 1948, leaving an estate if £250,221. His attitude to workers is the opposite of the Porters, and the company runs many social schemes.

They donate generously to the Clydeside Air Raid Distress Fund following the Clydebank Blitz in 1941, and on his death Hetherington leaves significant sums to churches, hospitals, the Salvation Army, schools and other public institutions.

For a company with deeply troubling colonialist beginnings, Galbraith's 34 years at the helm cements its reputation as a beloved household brand, which made its name in custard but largely seems to be remembered for its chemistry set soft drinks. 🔚

🧵➡️📄Unrolled thread, as 1 easy to read webpage. threadreaderapp.com/thread/1562920…

If you like this thread and got to the end, you'll probably like getting to the end of some of my other threads too. 👇

https://twitter.com/cocteautriplets/status/1561798261622640644?s=20&t=I3g9-EqWFoeIWAEDcBQ7zw

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh