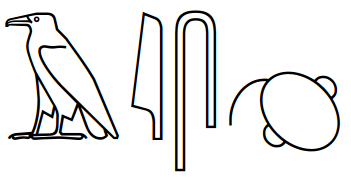

Here's a fun story about the earliest known neurological text: the Edwin Smith Papyrus. #histmed #NeuroTwitter #NeuroHistory

Edwin Smith, born in Connecticut, lived in Egypt in the late 1800s. An antiquities dealer, he bought a papyrus in 1862 that he was unable to translate.

Edwin Smith, born in Connecticut, lived in Egypt in the late 1800s. An antiquities dealer, he bought a papyrus in 1862 that he was unable to translate.

Smith died in 1906, and his daughter donated the scroll to the New York Historical Society.

In 1920, Egyptologist Caroline Ransom Williams found it and recognized its worth. She wrote to her mentor James Henry Breasted and asked him to translate it. brewminate.com/the-contributi…

In 1920, Egyptologist Caroline Ransom Williams found it and recognized its worth. She wrote to her mentor James Henry Breasted and asked him to translate it. brewminate.com/the-contributi…

Ransom Williams felt she was too occupied with family to take it on.

“The papyrus is probably the most valuable one owned by the Society and I am ready to waive my interest in it, in the hope that it may be published sooner and better than I could do it.” [November 22, 1920]

“The papyrus is probably the most valuable one owned by the Society and I am ready to waive my interest in it, in the hope that it may be published sooner and better than I could do it.” [November 22, 1920]

In 1930, Breasted published a translation of the papyrus, with the help of Dr. Arno B. Luckhardt, a physiologist and professor at @UChicago with an interest in medical history (he was particularly interested in the discoveries of Dr. William Beaumont).

The Edwin Smith papyrus has been dated to 1600 B.C.E., but based on the writing, it's thought to be a copy of another text from 1900 B.C.E.

That makes it the oldest surviving medical text.

That makes it the oldest surviving medical text.

It contains descriptions, exams, and treatments for 48 injuries - mostly sustained by young, healthy men in battle or construction.

Injuries fall in 3 categories: 1) An ailment I will handle; 2) An ailment I will fight with; and 3) An ailment for which nothing can be done.

Injuries fall in 3 categories: 1) An ailment I will handle; 2) An ailment I will fight with; and 3) An ailment for which nothing can be done.

...and because these cases start from the head and move downward, you get NEUROLOGY.

You get descriptions of meninges, cerebrospinal fluid, dural pulsations, and brain anatomy. Plus, prognostication, and a pattern of paralysis following brain injury.

You get descriptions of meninges, cerebrospinal fluid, dural pulsations, and brain anatomy. Plus, prognostication, and a pattern of paralysis following brain injury.

What really strikes historians, though, is the rational observational nature of the work. Later writing, like the Ebers papyrus, is more magical, less connected to observation and science.

onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.10…

onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.10…

Also, the Edwin Smith Papyrus contains the first known use of an asterisk (the red cross in this photo).

nature.com/articles/sc198…

nature.com/articles/sc198…

Here are pictures of the papyrus itself (I couldn't get the enlarged photos to work, but maybe you can):

digitalcollections.nyam.org/islandora/obje…

digitalcollections.nyam.org/islandora/obje…

And here's a pdf of Breasted's entire translation:

oi.uchicago.edu/sites/oi.uchic…

Enjoy your weekend!

oi.uchicago.edu/sites/oi.uchic…

Enjoy your weekend!

(I feel like, if we have to name this papyrus after someone, it shouldn't be the guy who showed up in Egypt, bought it, and then did nothing with it. Can we call this the Caroline Ransom Williams Papyrus? Ok, the Breasted Papyrus, if we must.)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh