It is 335 years to the day since an explosion ripped apart the Parthenon on the evening of September 26 1687.

Drawing by Mannolis Korres).

Drawing by Mannolis Korres).

As part of the Morean War (also known as the 6th Ottoman Venetian War), Venetian forces has landed on the Peloponnese (then known as Morea).

Venetian commanders under Francesco Morosini (pictured) decided to expand their campaign, with Athens as the first target.

Venetian commanders under Francesco Morosini (pictured) decided to expand their campaign, with Athens as the first target.

The Ottoman Turks who controlled Athens at this time evacuated the town of Athens, with the garrison and many of the civilians retreating to the Acropolis to wait for reinforcements from Thebes.

Venetian forces set up cannons on the Pnyx (a small rocky hill - and the area of high ground closest to the Acropolis). This hill had great historical significance in ancient Athens as once of the sites of popular assemblies & hence an important site in the creation of democracy.

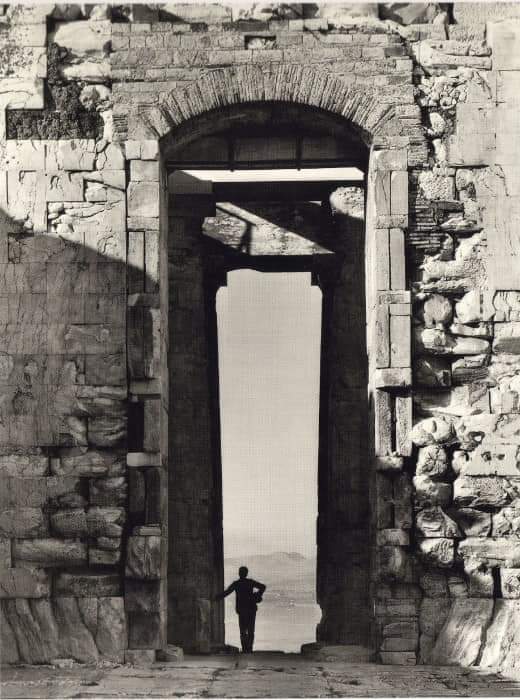

The Ottomans demolished the temple of Athena Nike to erect a canon battery there and and used the stone from the temple as extra defenses to the entrance to the Acropolis (see this thread).

https://twitter.com/elginism/status/1573032955483754501

On 25th September, a Venetian cannonball caused an explosion in a powder magazine in the Propylaia (see linked thread for more on this building).

https://twitter.com/elginism/status/1573016449979150336

Then, the following day a cannonball hit the Parthenon, triggering a massive explosion within the building, which had been used for storing ammunition by the Ottomans. The explosion killed 300 people and destroyed the roof and walls of the Parthenon.

Up until this time, although it had been converted for use as a mosque and a minaret added, the Parthenon was still relatively intact - as shown in this drawing 13 years prior to the explosion by Jacques Carrey.

In an instant, the Parthenon was transformed from a relatively intact building, with roof and walls and most of its sculptural decoration into the ruined form we are so familiar with today.

Loss of the roof and inner walls increased the rate of collapse of the building, leaving everything exposed to the elements.

Since then, painstaking restoration works have re-assembled as many of the fallen pieces as can be reliably identified.

Since then, painstaking restoration works have re-assembled as many of the fallen pieces as can be reliably identified.

But we are still a very long way off getting the building back to where it was 336 years ago before this tragic day in the building's history.

Who was to blame? The Ottomans arguably shouldn't have been storing ammunition in a historic building (or for that matter a mosque), but at the same time, they were doing whatever it took to defend themselves.

For me, the real villain in this story was Morosini - the one who described the enormous destruction caused by his troops as a "miraculous shot".

Despite the explosion, the Ottomans managed to hold onto the fort for another two days, before news reached them that their relief from Thebes had been forced back and they then capitulated on the condition they were transported to Smyrna the following day.

In the aftermath of this, Venetian forces tried to recruit Greeks from rural Attica as soldiers, but struggled to get more than a few hundred troops this way. By the end of the year the Venetians had made a decision to abandon Athens.

This was not the end of the damage to the Acropolis site though. On 19 March 1688, Morosini's men while trying to remove sculptures from the Parthenon, accidentally allowed the statue of Poseidon and the Chariot of Nike to fall from the west pediment and smash to pieces.

They also took the famous Pireaus Lion which still stands at the entrance to the Venetian Arsenal today.

On 10 April 1688, the Venetian forces left Attica and retreated to the Peloponnese - closing this chapter of the Parthenon's history - but leaving it open for the later arrival of Lord Elgin to find it in a ruined state and get permission to remove stones lying on the ground.

If it had not been part ruined & there had been no stones lying on the ground, would Elgin still have got permission to do what he did? Possibly, but I can imagine that the outcry at the time might have been far greater if he was dismantling an intact building rather than ruins.

We should also remember (when thinking about the above) that the whole Parthenon had been used as a mosque (rather than the later situation of a mosque built within the ruins).

It's hard to imagine the Ottomans agreeing to its dismemberment.

It's hard to imagine the Ottomans agreeing to its dismemberment.

One last point - If the building was intact, it would have been far harder for Elgin to remove the sculptures still on it too - the frieze panels & metopes were integral to its structure and held in place by structure above. Before the explosion...

Artwork by Tinatin Mangasarian

Artwork by Tinatin Mangasarian

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh