In my speech @ForoLaToja in beautiful Galicia I talked about “Monetary policy in a cost-of-living crisis” and had an interesting panel discussion about inflation with my former colleague Carlos Costa and with Antón Costas @CESEspana, moderated by Alejandra Kindelán @Aebanca. 1/15

https://twitter.com/ecb/status/1575869503367680000

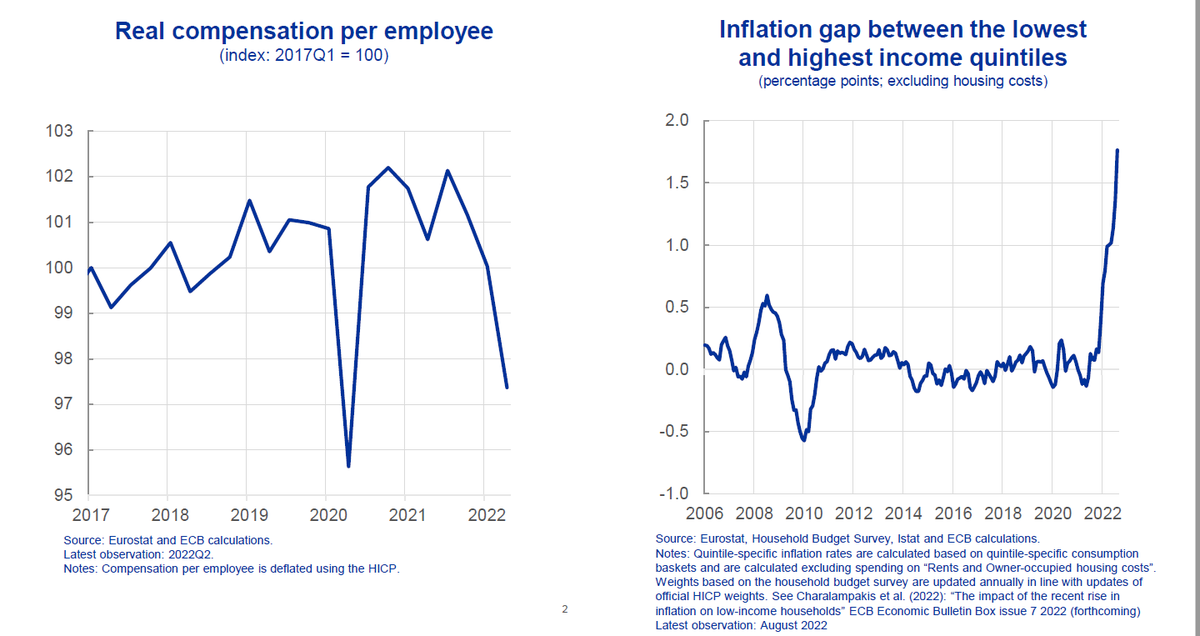

High inflation means that many people are suffering a concerning loss in their purchasing power as their real, that is inflation-adjusted, wages are declining. My speech discusses what this decline in real wages means for monetary policy. 2/15

Real consumer wages in the euro area have declined by nearly 5% since 2021 Q3. Low-income households are most affected. The difference between the inflation rate of the lowest- and highest-income households has risen markedly. 3/15

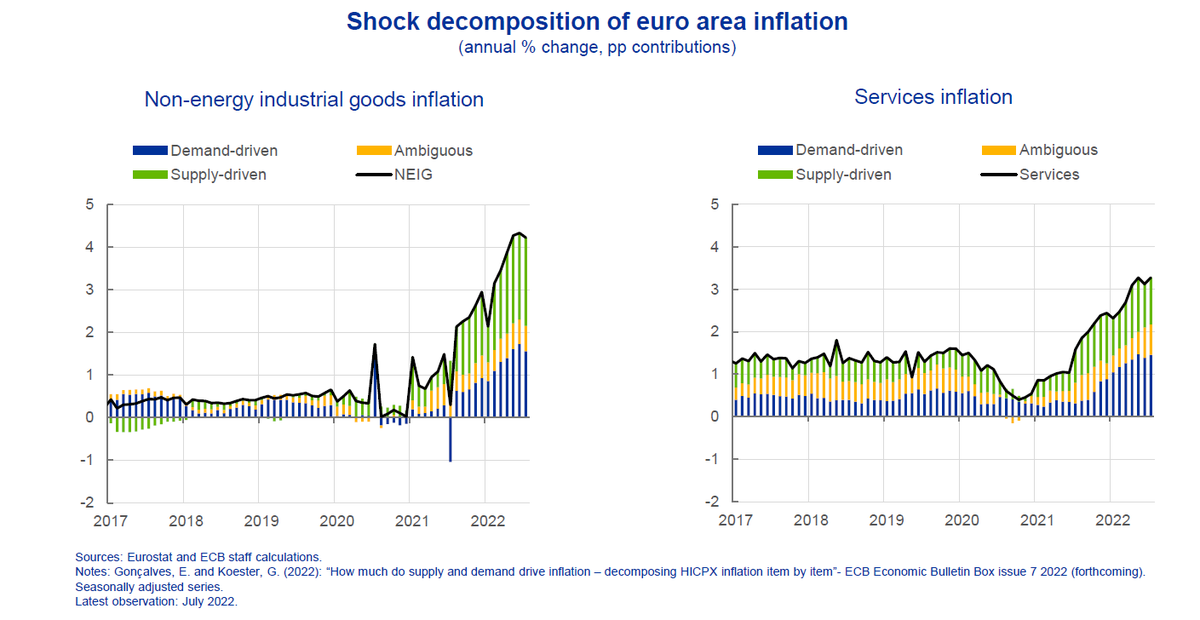

Real wages matter for monetary policy because they affect private consumption and hence aggregate demand (“demand channel”). Demand factors have contributed to the rise in inflation in the euro area, both for goods and services. 4/15

The demand channel points to easing inflationary pressures going forward. Falling real wages have contributed to the sharp decline in consumer confidence. This will weigh on demand and should, in isolation, ease inflationary pressures. 5/15

Real wages are also an important part of firms’ costs (“cost-push channel”). Real labour costs deflated by producer prices have fallen and profits have increased, suggesting that labour costs are not currently adding to inflationary pressures. 6/15

Will real wages continue to decline? This will depend, among other things, on fiscal policy. Targeted fiscal measures can support those suffering the most from the current crisis. But too broad-based fiscal measures could reinforce inflationary pressures. 7/15

The evolution of real wages will also depend on workers’ bargaining power. Over the past decades, the labour income share fell significantly, coinciding with a decline in trade union density, while the profit share increased. 8/15

But nominal wage growth has recently accelerated. Whether future wage agreements will lead to a wage-price spiral ultimately depends on monetary policy. If long-term inflation expectations remain anchored, the risks of a wage-price spiral will be limited. 9/15

To what extent will a decline in real wages ease inflationary pressures? Inflation may remain high because the damage from the current crisis to the supply side is likely to be significant, meaning that lower demand may not necessarily lead to larger slack. 10/15

Current order books confirm this view. Despite a notable slowdown in new orders, euro area firms are only slowly reducing the backlog of orders stemming from the pandemic. This suggests that significant supply-side constraints remain. 11/15

Firms’ efforts to protect their profit margins may also limit downward pressure on inflation. Firms may not pass lower real labour costs on to consumer prices. In fact, firms plan to raise prices further because of higher energy costs. 12/15

It would thus be imprudent to assume that slowing demand reduces the need for raising rates. High underlying inflation and prospects of continued high inflation mean that monetary policy must ensure that inflation expectations remain anchored. 13/15

Doing so means that, at times of large disruptive change, central banks cannot narrowly rely on uncertain model-based forecasts. A “robust control” approach puts more weight on incoming data to assess the risks of a de-anchoring. 14/15

Given these data and the above-target medium-term inflation outlook, further increases in our key policy rates will be needed to ensure that inflation returns to our 2% target in a timely manner. See the full speech for all arguments and references. 15/15 ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh