There has been significant attention to Iran's internet blackouts.

Time to dig into what's happening inside Iran, and whether outsiders can help. What I found was surprisingly chaotic, nightmarish.

An ongoing thread. #MahsaAmini #IranProtests2022 #مهسا_امینی #OpIran #KeepitOn

Time to dig into what's happening inside Iran, and whether outsiders can help. What I found was surprisingly chaotic, nightmarish.

An ongoing thread. #MahsaAmini #IranProtests2022 #مهسا_امینی #OpIran #KeepitOn

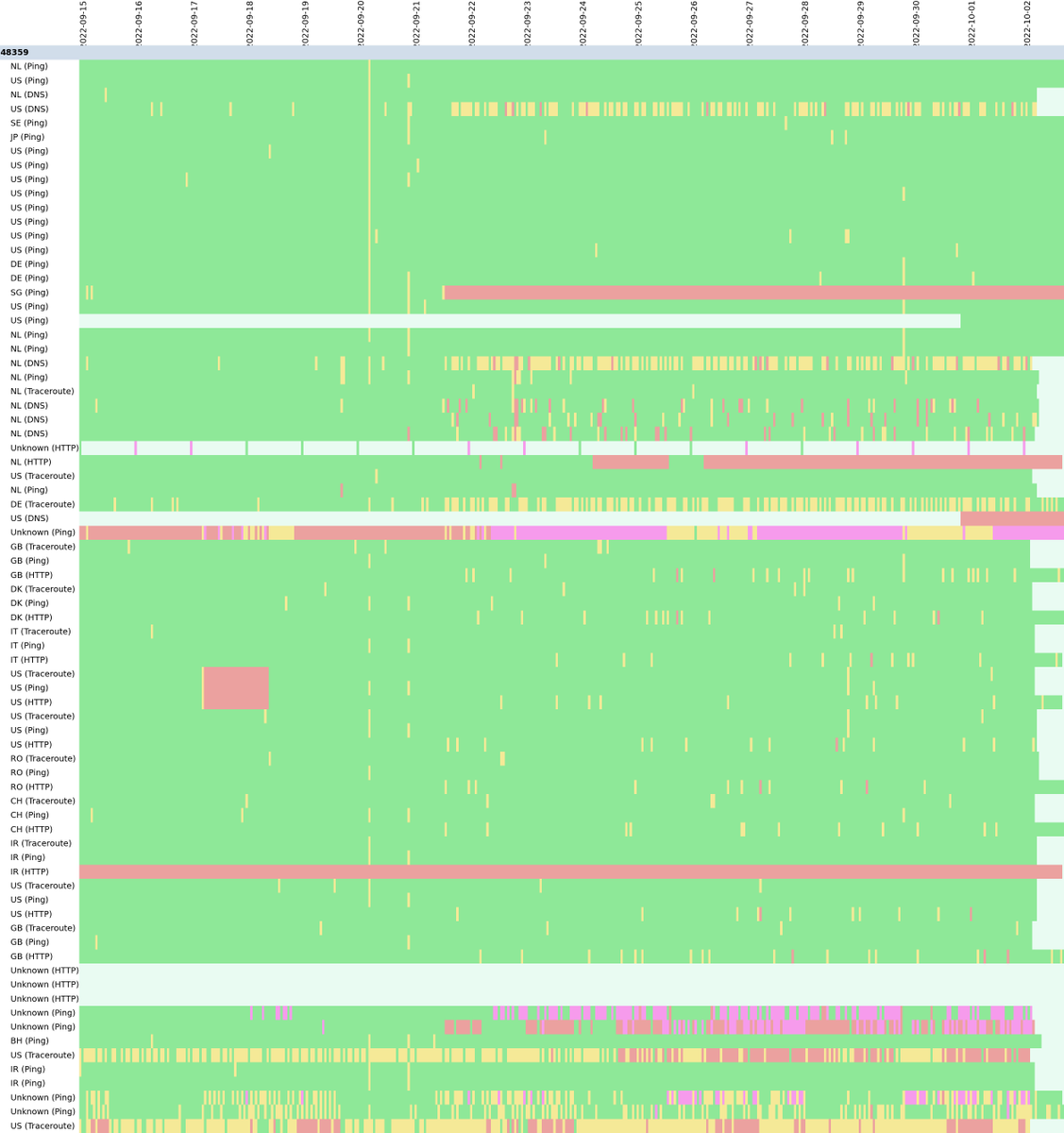

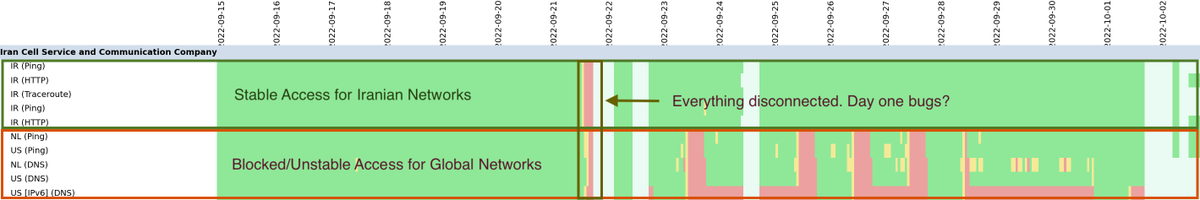

Overall, as many have noted, Iran has essentially been under an Internet curfew since September 21 (until possibly yesterday).

Every afternoon around 4pm local time until midnight, traffic from Iran would drop precipitously, across the board.

Every afternoon around 4pm local time until midnight, traffic from Iran would drop precipitously, across the board.

https://twitter.com/DougMadory/status/1577341946783318035

The first finding: despite heavy investments in censorship, Iran still does not seem to have a central, single kill switch.

Instead, each ISP seems to have their own tactics for cutting off access. The Telecommunication Company of Iran (TCI) then is a fallback for censorship.

Instead, each ISP seems to have their own tactics for cutting off access. The Telecommunication Company of Iran (TCI) then is a fallback for censorship.

For example, the mobile carrier Rightel, would every evening disappear half their IP addresses from the global Internet, making them unreachable (i.e. withdraw from BGP). From Rightel's descriptions, those are IPs for 3G/4G service.

Its competitors Irancell and MCI, do not.

Its competitors Irancell and MCI, do not.

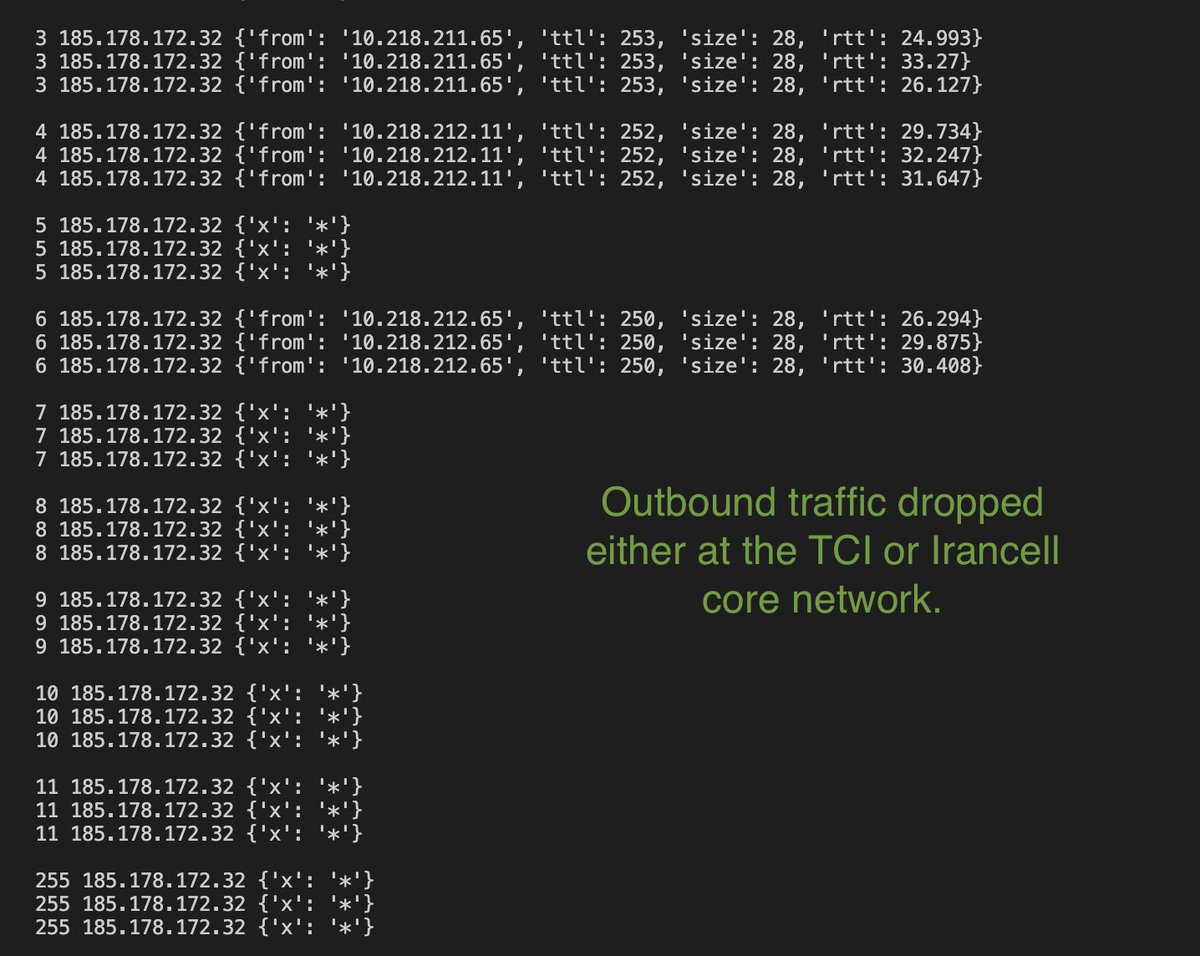

Instead, others are either blocking web traffic or using deep packet inspection to restrict access.

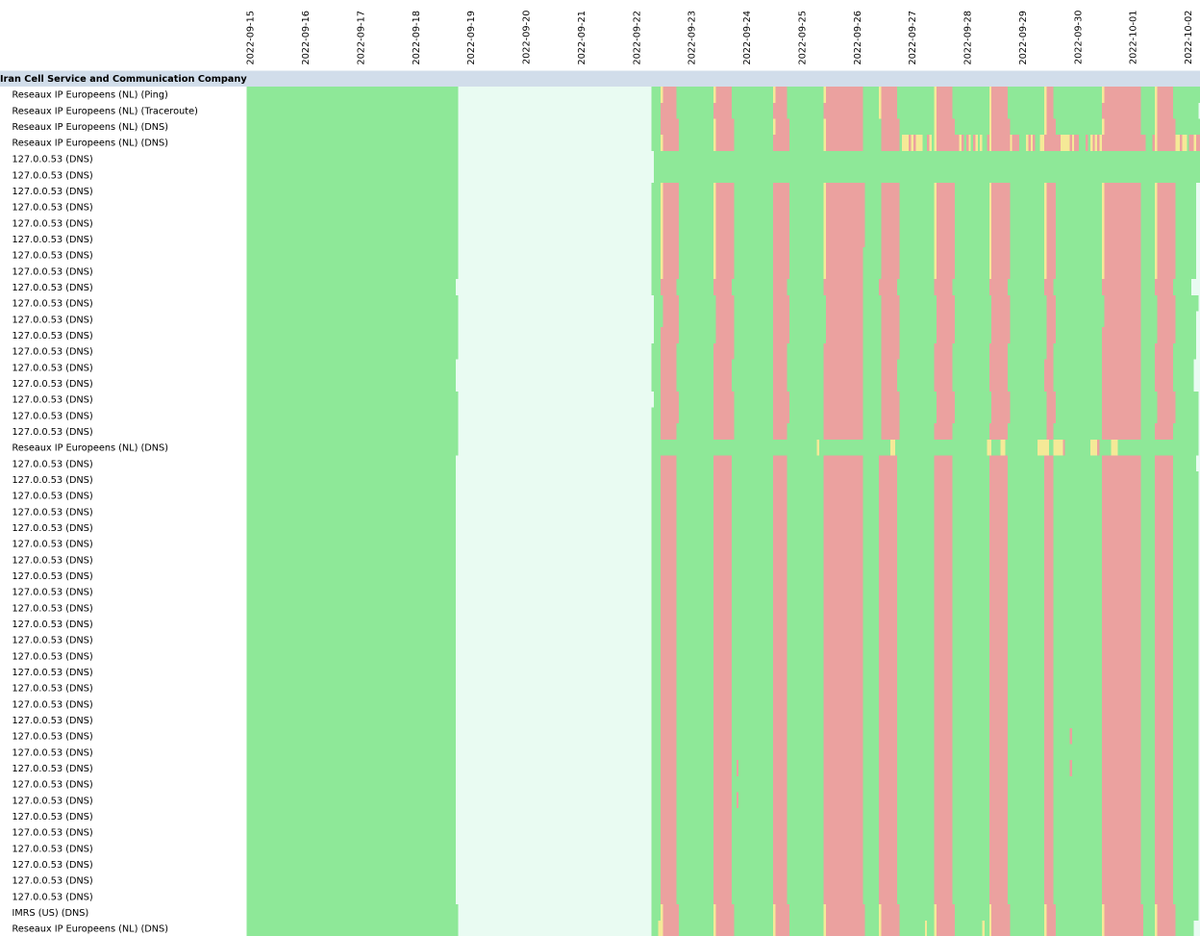

For example, DSL provider Asiatech appears to be interfering with DNS queries. Irancell seems to be both interfering with HTTP traffic, and sometimes dropping all traffic.

For example, DSL provider Asiatech appears to be interfering with DNS queries. Irancell seems to be both interfering with HTTP traffic, and sometimes dropping all traffic.

One big caveat —

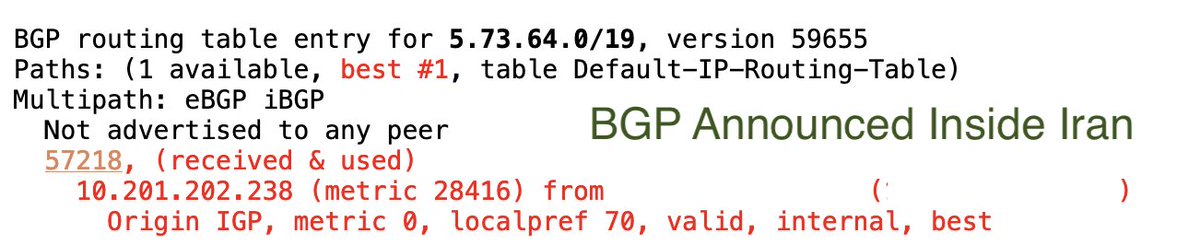

Actually, those millions of Rightel customers can still reach domestic websites.

That's because. while Rightel cut them off from the global internet, it was still announcing them to other Iranian networks. Other ISPs seem to exempting domestic traffic too.

Actually, those millions of Rightel customers can still reach domestic websites.

That's because. while Rightel cut them off from the global internet, it was still announcing them to other Iranian networks. Other ISPs seem to exempting domestic traffic too.

The longtime nightmare of Iran being able to cleanly/quickly disconnect from the global internet, while keeping the censored domestic internet online, appears to have true.

This appears across different ISPs, e.g. Irancell.

This appears across different ISPs, e.g. Irancell.

Appears TCI has stepped up its filtering at the international gateway. This is Iran's more sophisticated backstop.

On Sept 22nd, connections to Cloudflare using QUIC went to near zero instantaneously across ISPs. Probably only happens if TCI is doing it, probably based on DPI?

On Sept 22nd, connections to Cloudflare using QUIC went to near zero instantaneously across ISPs. Probably only happens if TCI is doing it, probably based on DPI?

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh