Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance (MGUS).

Present in ~5% of all people age 50+

Therefore something all clinicians should know about. Brief summary.

#medtwitter @ESHaematology

1/

Present in ~5% of all people age 50+

Therefore something all clinicians should know about. Brief summary.

#medtwitter @ESHaematology

1/

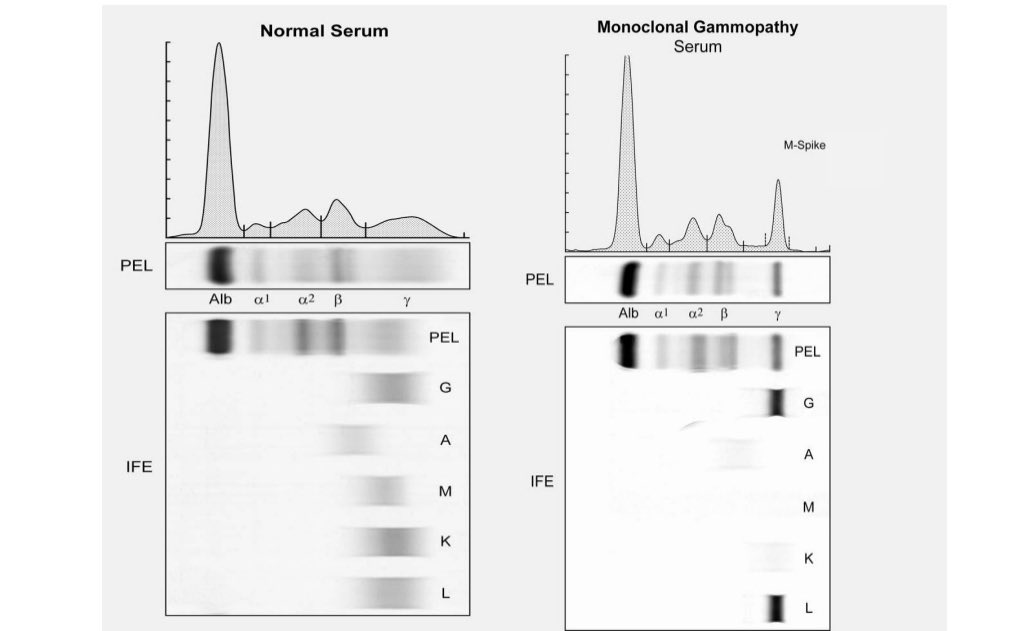

MGUS shows up on a serum protein electrophoresis (PEL) as a spike. See figure. The spike is called an M spike.

It can be typed on immunofixation (IFE) to determine if it’s IgG or IgM or IgA; kappa or lambda. See below.

2/

It can be typed on immunofixation (IFE) to determine if it’s IgG or IgM or IgA; kappa or lambda. See below.

2/

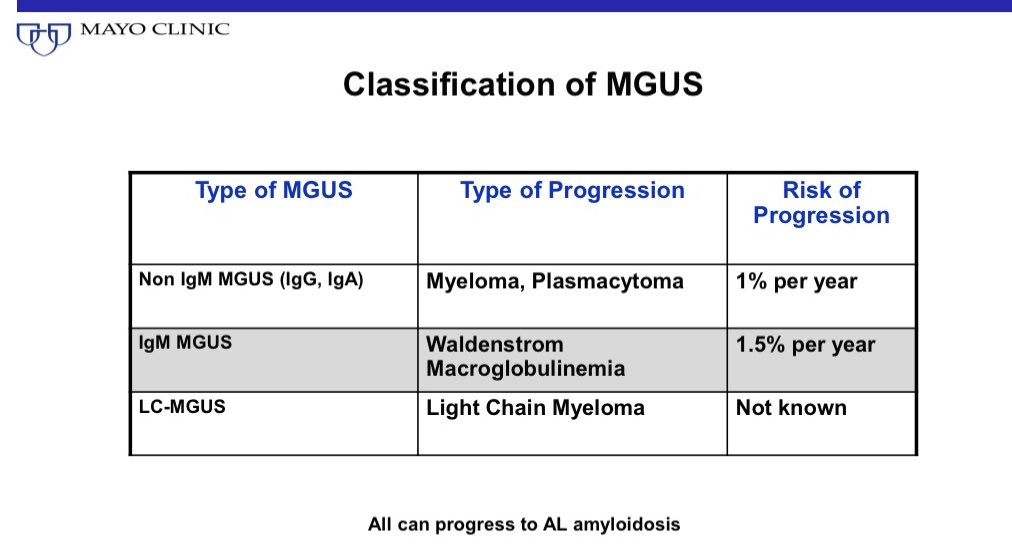

MGUS was a term coined by Dr. Kyle.

He called It MGUS because prior to that it was called benign monoclonal gammopathy. Since he found a 1% per year risk of progression to myeloma he felt it the word “benign” may not capture the clinical implications adequately.

2/

He called It MGUS because prior to that it was called benign monoclonal gammopathy. Since he found a 1% per year risk of progression to myeloma he felt it the word “benign” may not capture the clinical implications adequately.

2/

MGUS is defined by M protein less than 3 gm per dl, and no myeloma defining events (MDE). A bone marrow if done should have less than 10% clonal plasma cells. (Not every patient with likely MGUS needs a marrow as I explain later; in fact most don’t). @TheLancetOncol

3/

3/

MGUS was first estimated to be present in 3% of the population age 50+.

Prevalence is higher in men. And goes up with age. @NEJM

4/

Prevalence is higher in men. And goes up with age. @NEJM

4/

When we add light chain MGUS (detected in serum free light chain assay) and use more sensitive mass spectrometry techniques the prevalence of MGUS is higher. Approximately 5% of the population age 50+

5/

5/

The prevalence of MGUS is 2-3 times higher in first degree relatives of people with MGUS or myeloma.

But note myeloma incidence is only 4/100,000 per year. So 3 fold higher 12/100,000 is still a low risk.

6/

But note myeloma incidence is only 4/100,000 per year. So 3 fold higher 12/100,000 is still a low risk.

6/

Prevalence of MGUS is also 2-3 fold higher in Black people. The higher prevalence of MGUS in Black people is the main reason for the higher prevalence of myeloma in this population

MGUS also occurs at an earlier age in Black people. @DrOlaLandgren led a lot of these studies.

7/

MGUS also occurs at an earlier age in Black people. @DrOlaLandgren led a lot of these studies.

7/

But if one is not careful or experienced, you can start calling every little “spike” on mass spec a monoclonal protein. Then you end up calling half of the world as having MGUS.

(If we said BP >100 systolic is hypertension, then the prevalence of hypertension skyrockets).

9/

(If we said BP >100 systolic is hypertension, then the prevalence of hypertension skyrockets).

9/

As an aside, lot of us would want to define a new disease for the first time

Dr. Kyle shows us how it’s done: He first set a specific disease definition; studied for years what the implications are with that disease definition; estimated the prevalence; made recommendations

10/

Dr. Kyle shows us how it’s done: He first set a specific disease definition; studied for years what the implications are with that disease definition; estimated the prevalence; made recommendations

10/

MGUS is associated with an approximately 1% risk of progression to myeloma or related disorder. @NEJM

12/

12/

The progression risk persists indefinitely. But we are mortal and susceptible to lots of other diseases besides myeloma. So in reality the real risk of progression of MGUS to myeloma or related disorder over a lifetime is only 10%.

90% NEVER progress until death. @NEJM

13/

90% NEVER progress until death. @NEJM

13/

MGUS can be risk stratified using 3 simple factors: M spike >1.5 gm/dl, abnormal free light chain ratio, and non IgG type of MGUS are all risk factors.

If there are no risk factors, risk of progression over a whole lifetime is only 2%. Today that’s most of MGUS we diagnose!

14/

If there are no risk factors, risk of progression over a whole lifetime is only 2%. Today that’s most of MGUS we diagnose!

14/

If an MGUS is suspected, not everyone needs a marrow or bone survey. Choosing wisely. The yield of these tests in low risk patients is close to zero.

You can omit marrow & bone imaging in uncomplicated patients with low risk MGUS, small IgM MGUS, light chain MGUS with ratio <8.

You can omit marrow & bone imaging in uncomplicated patients with low risk MGUS, small IgM MGUS, light chain MGUS with ratio <8.

All patients with new diagnosis of MGUS should have a CBC, creat, calcium, protein electrophoresis and serum free light chain assay rechecked in 6 months. And if stable further follow up can be only at time of symptoms in low risk patients.

Yearly thereafter for all others. 16/

Yearly thereafter for all others. 16/

MGUS can be associated with several other disorders even without progression to myeloma or Waldenstroms Macroglobulinemia. This is often because the secreted monoclonal protein is an actual functioning antibody that is targeting something in the body.

17/

17/

So clinicians should be aware of these associations.

A lot of associations are coincidental not causal. Knowing how to differentiate takes time and experience. No easy way out.

18/

A lot of associations are coincidental not causal. Knowing how to differentiate takes time and experience. No easy way out.

18/

Should we screen for MGUS? No, in general.

There are however specific populations that I feel a one time screening test is warranted at age 40+: Black people with one affected first degree relative with myeloma & all others with 2 or more first degree relatives with myeloma. 19/

There are however specific populations that I feel a one time screening test is warranted at age 40+: Black people with one affected first degree relative with myeloma & all others with 2 or more first degree relatives with myeloma. 19/

For more on MGUS check this article. #OpenAccess @ASH_hematology @BloodJournal ashpublications.org/blood/article/…

For more on my rationale for screening high risk populations for MGUS check this out. @Nature nature.com/articles/d4158…

Here is a comprehensive Review article on MGUS.

https://twitter.com/VincentRK/status/1605336922611716097

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh