"Probability is the logic of science."

There is a deep truth behind this conventional wisdom: probability is the mathematical extension of logic, augmenting our reasoning toolkit with the concept of uncertainty.

In-depth exploration of probabilistic thinking incoming.

There is a deep truth behind this conventional wisdom: probability is the mathematical extension of logic, augmenting our reasoning toolkit with the concept of uncertainty.

In-depth exploration of probabilistic thinking incoming.

Our journey ahead has three stops:

1. an introduction to mathematical logic,

2. a touch of elementary set theory,

3. and finally, understanding probabilistic thinking.

First things first: mathematical logic.

1. an introduction to mathematical logic,

2. a touch of elementary set theory,

3. and finally, understanding probabilistic thinking.

First things first: mathematical logic.

In logic, we work with propositions.

A proposition is a statement that is either true or false, like

• "it's raining outside",

• "the sidewalk is wet".

These are often abbreviated as variables, such as A = "it's raining outside".

A proposition is a statement that is either true or false, like

• "it's raining outside",

• "the sidewalk is wet".

These are often abbreviated as variables, such as A = "it's raining outside".

We can formulate complex propositions from smaller building blocks with logical connectives.

Consider the proposition "if it is raining outside, then the sidewalk is wet". This is the combination of two propositions, connected by the implication connective.

Consider the proposition "if it is raining outside, then the sidewalk is wet". This is the combination of two propositions, connected by the implication connective.

There are four essential connectives:

• NOT (¬), also known as negation,

• AND (∧), also known as conjunction,

• OR (∨), also known as disjunction,

• THEN (→), also known as implication.

• NOT (¬), also known as negation,

• AND (∧), also known as conjunction,

• OR (∨), also known as disjunction,

• THEN (→), also known as implication.

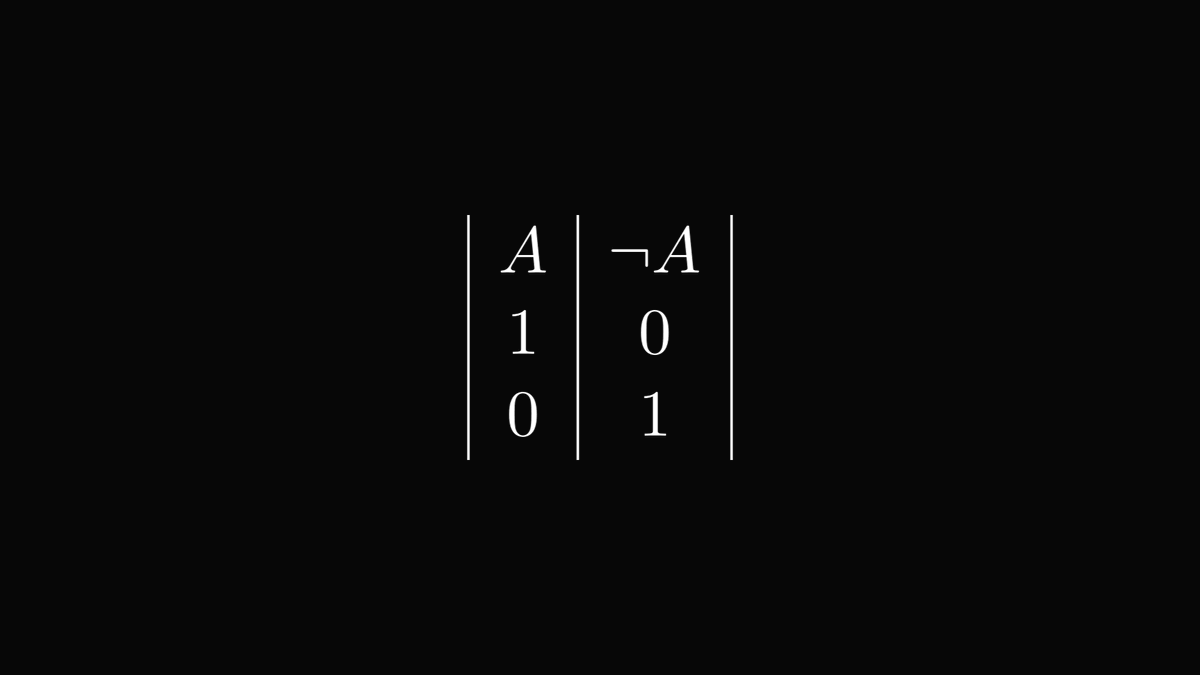

Connectives are defined by the truth values of the resulting propositions. For instance, if A is true, then NOT A is false; if A is false, then NOT A is true.

Denoting true by 1 and false by 0, we can describe connectives with truth tables. Here is the one for negation (¬).

Denoting true by 1 and false by 0, we can describe connectives with truth tables. Here is the one for negation (¬).

AND (∧) and OR (∨) connect two propositions. A ∧ B is true if both A and B are true, and A ∨ B is true if either one is.

The implication connective THEN (→) formalizes the deduction of a conclusion B from a premise A.

By definition, A → B is true if B is true or both A and B are false.

An example: if "it's raining outside", THEN "the sidewalk is wet".

By definition, A → B is true if B is true or both A and B are false.

An example: if "it's raining outside", THEN "the sidewalk is wet".

Science is just the collection of complex propositions like "if X is a closed system, THEN the entropy of X cannot decrease". (As the 2nd law of thermodynamics states.)

The entire body of scientific knowledge is made of A → B propositions.

The entire body of scientific knowledge is made of A → B propositions.

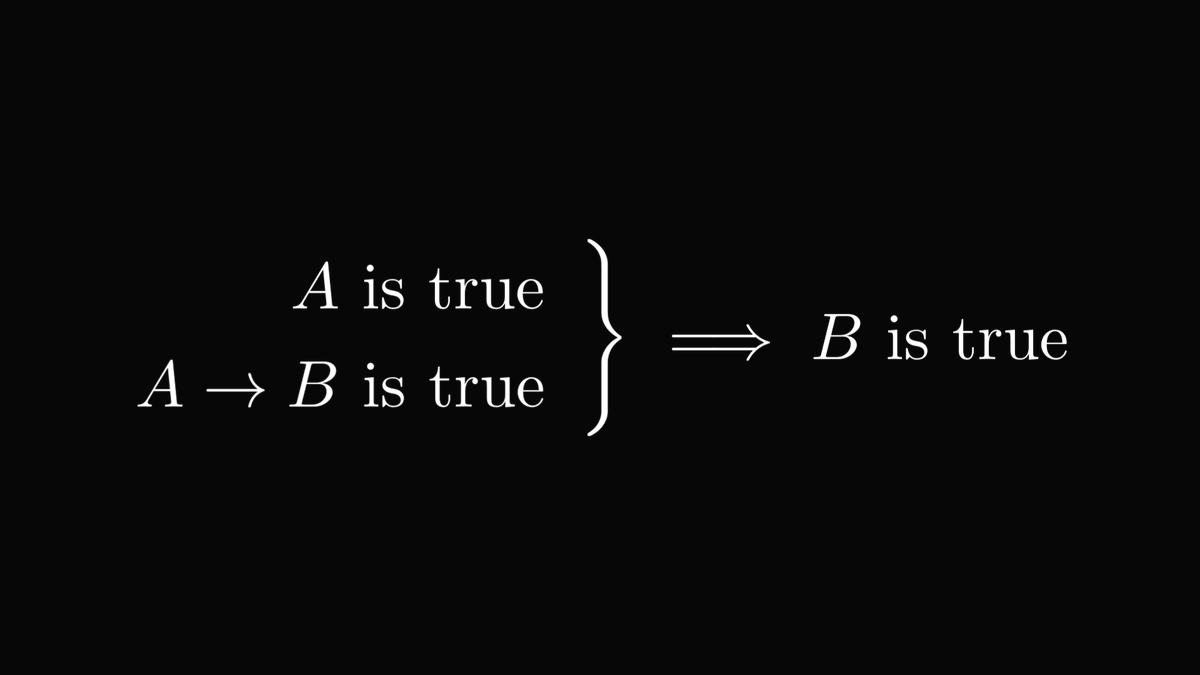

In practice, our thinking process is the following.

"I know that A → B is true and A is true. Therefore, B must be true as well."

This is called modus ponens, the cornerstone of scientific reasoning.

"I know that A → B is true and A is true. Therefore, B must be true as well."

This is called modus ponens, the cornerstone of scientific reasoning.

(If you don't understand modus ponens, take a look at the truth table of the → connective, a few tweets above.

The case when A → B is true and A is true is described by the very first row, which can only happen if B is true as well.)

The case when A → B is true and A is true is described by the very first row, which can only happen if B is true as well.)

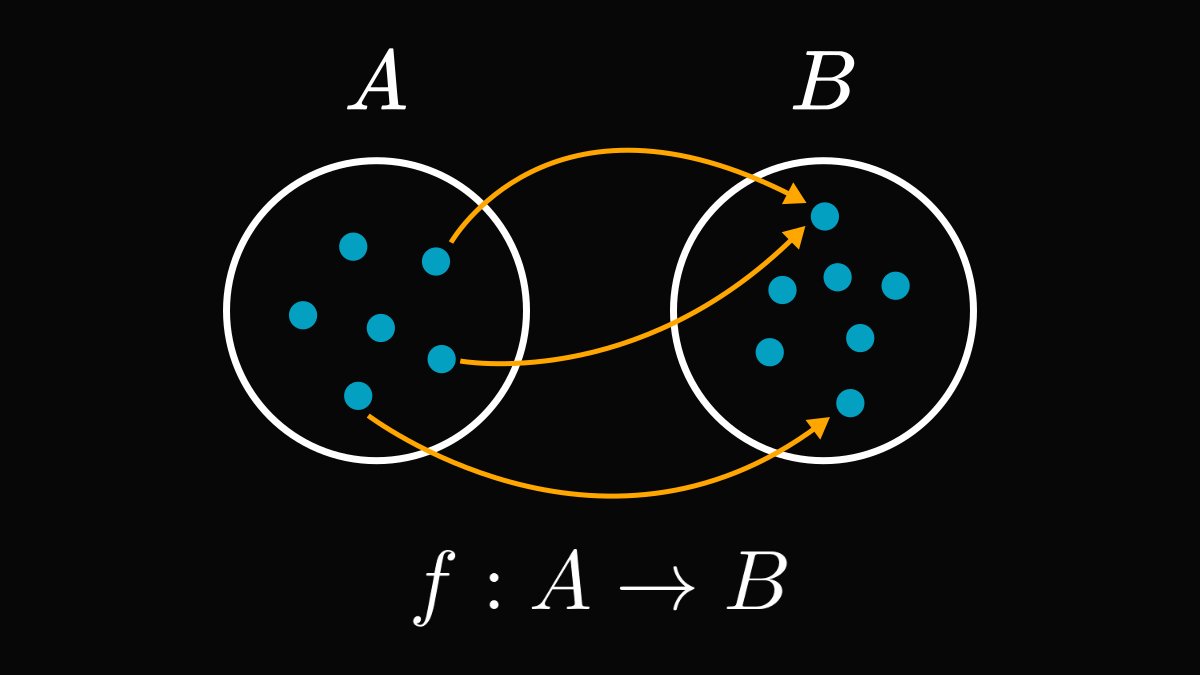

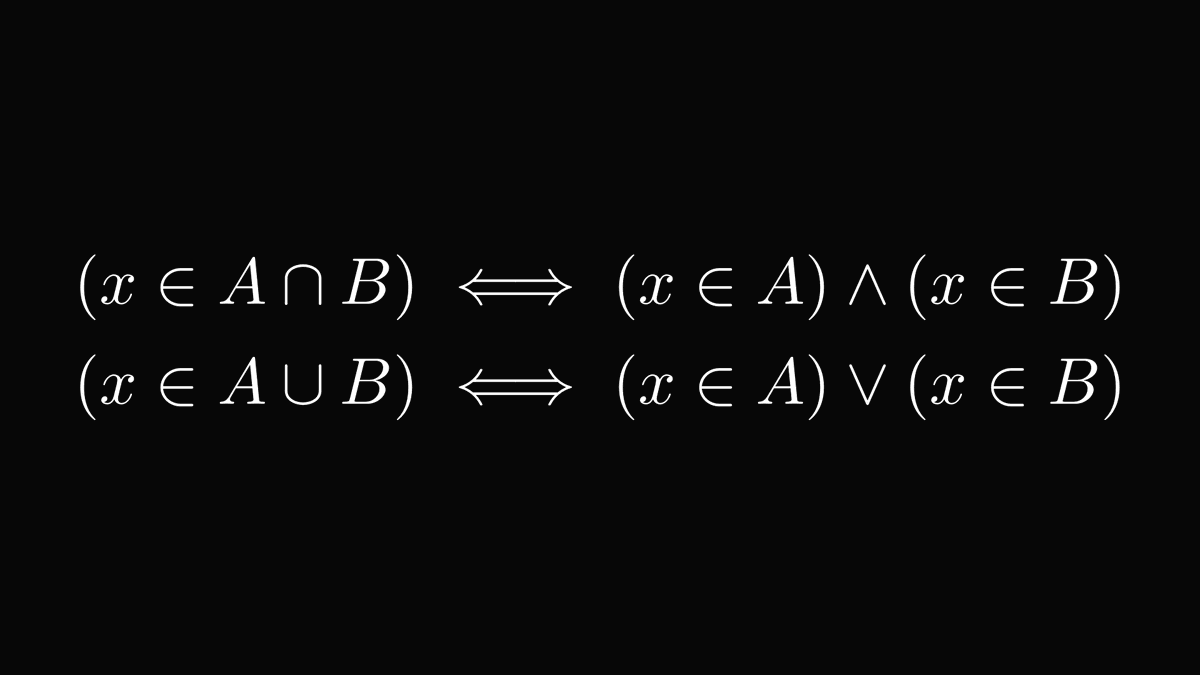

Logical connectives can be translated to the language of sets.

Union (∪) and intersection (∩), two fundamental operations, are particularly relevant for us.

Notice how similar the symbols for AND (∧) and intersection (∩) are? This is not an accident.

Union (∪) and intersection (∩), two fundamental operations, are particularly relevant for us.

Notice how similar the symbols for AND (∧) and intersection (∩) are? This is not an accident.

By definition, any element 𝑥 is the element of A ∩ B if and only if (𝑥 is an element of A) AND (𝑥 is an element of B).

Similarly, union corresponds to the OR connective.

Similarly, union corresponds to the OR connective.

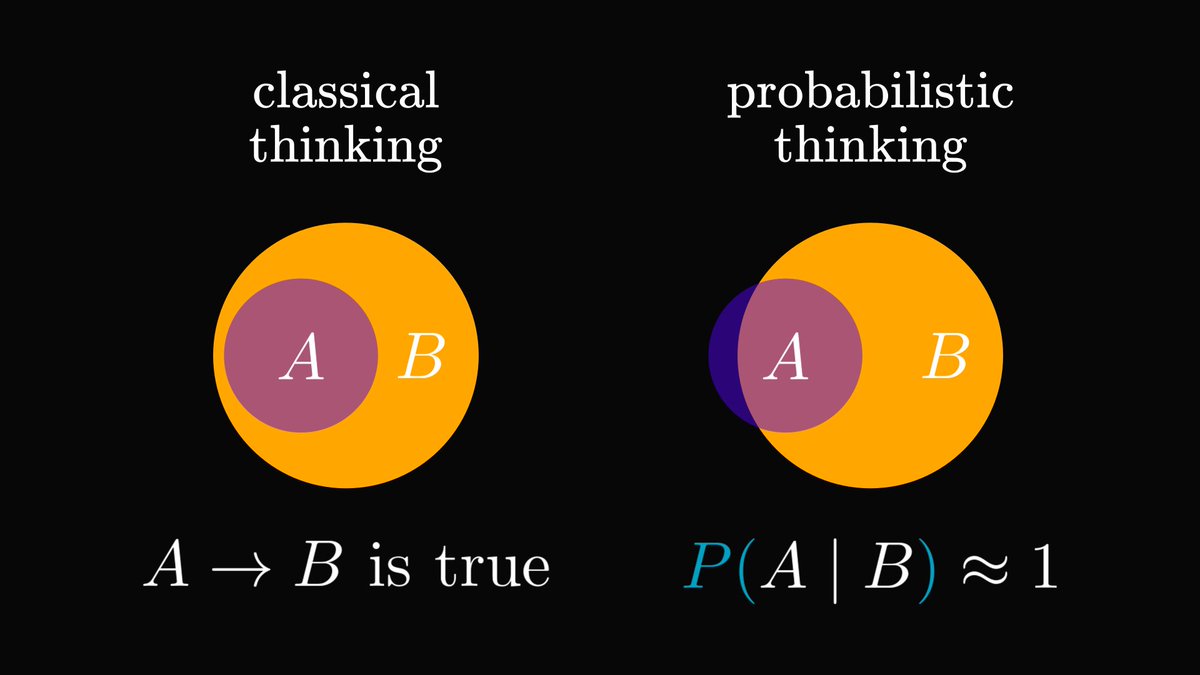

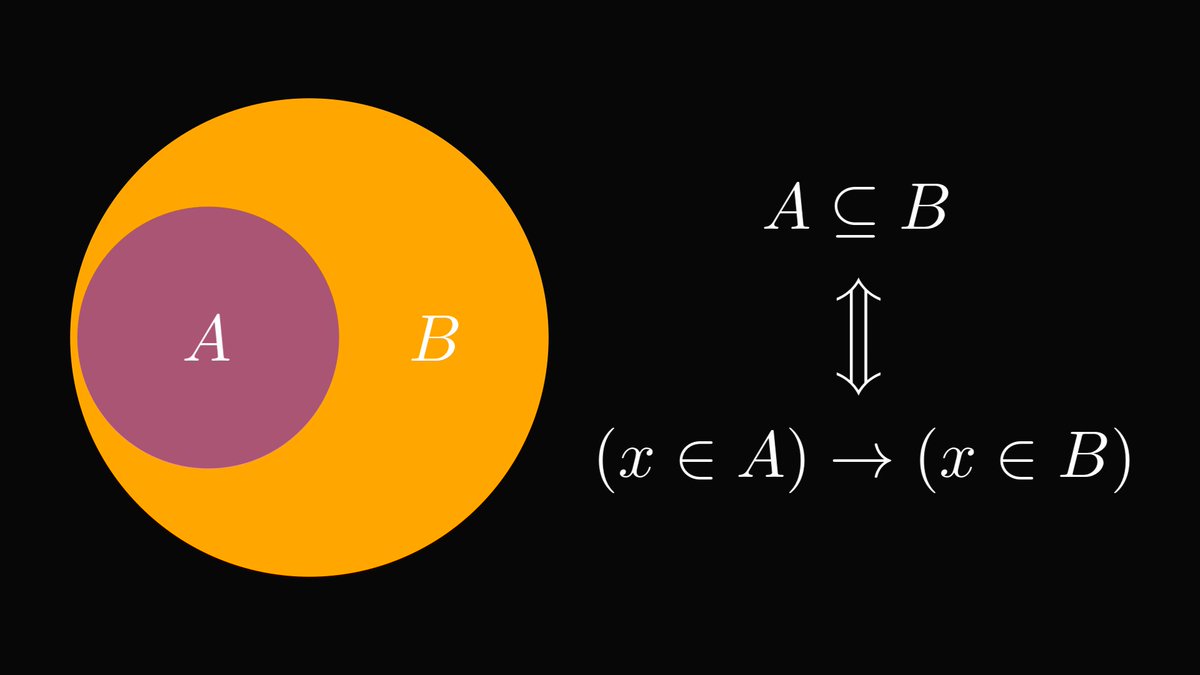

What's most important for us is that the implication connective THEN (→) corresponds to the "subset of" relation, denoted by the ⊆ symbol.

Now that we understand how to formulate scientific truths as "premise → conclusion" statements and see how this translates to sets, we are finally ready to talk about probability.

What is the biggest flaw of mathematical logic?

What is the biggest flaw of mathematical logic?

We rarely have all the information to decide if a proposition is true or false.

Consider the following: "it'll rain tomorrow". During the rainy season, all we can say is that rain is more likely, but tomorrow can be sunny as well.

Consider the following: "it'll rain tomorrow". During the rainy season, all we can say is that rain is more likely, but tomorrow can be sunny as well.

Probability theory generalizes classical logic by measuring truth on a scale between 0 and 1, where 0 is false and 1 is true.

If the probability of rain tomorrow is 0.9, it means that rain is significantly more likely, but not absolutely certain.

If the probability of rain tomorrow is 0.9, it means that rain is significantly more likely, but not absolutely certain.

Instead of propositions, probability operates on events. In turn, events are represented by sets.

For example, if I roll a dice, the event "the result is less than five" is represented by the set A = {1, 2, 3, 4}.

In fact, P(A) = 4/6. (P denotes the probability of an event.)

For example, if I roll a dice, the event "the result is less than five" is represented by the set A = {1, 2, 3, 4}.

In fact, P(A) = 4/6. (P denotes the probability of an event.)

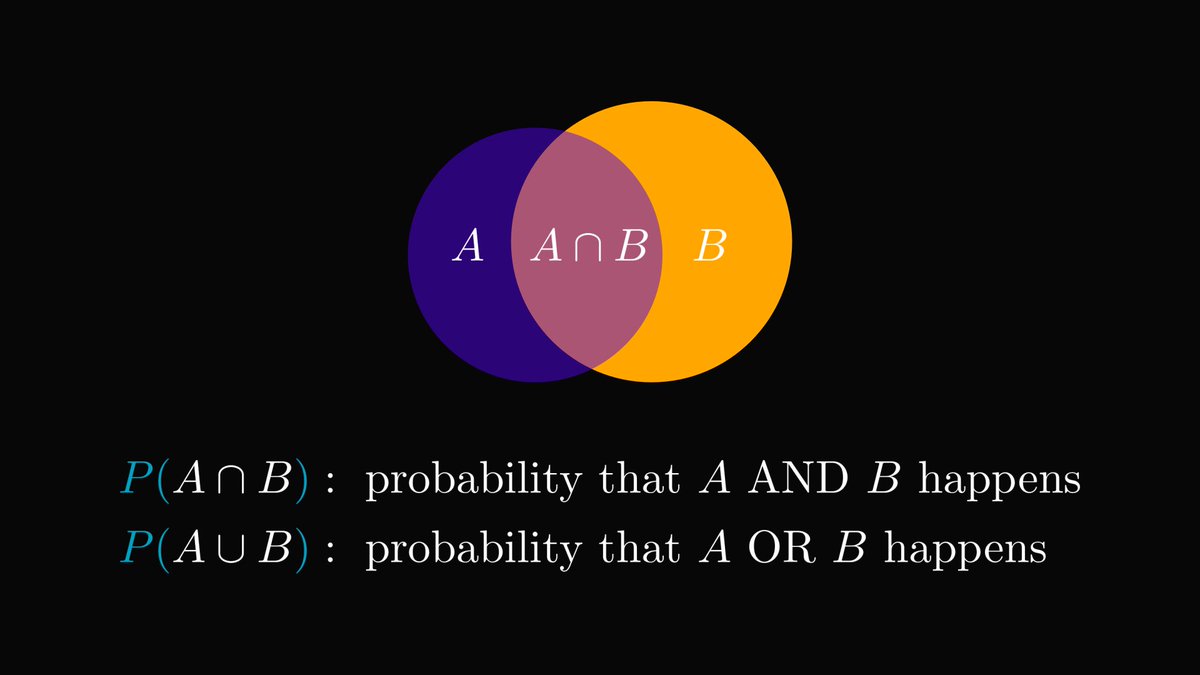

As discussed earlier, the logical connectives AND and OR correspond to basic set operations: AND is intersection, OR is union.

This translates to probabilities as well.

This translates to probabilities as well.

How can probability be used to generalize the logical implication?

A "probabilistic A → B" should represent the likelihood of B, given that A is observed.

This is formalized by conditional probability.

A "probabilistic A → B" should represent the likelihood of B, given that A is observed.

This is formalized by conditional probability.

(If you want to know more about conditional probabilities, here is a brief explainer.)

https://twitter.com/TivadarDanka/status/1492127542068666376

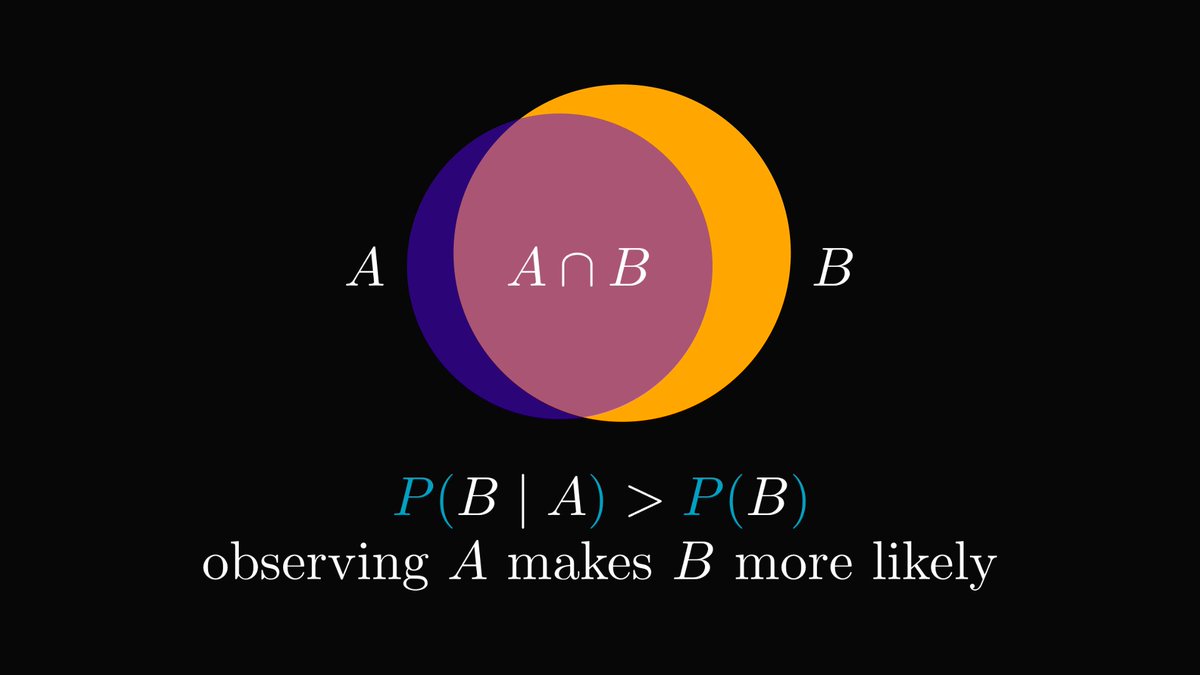

At the deepest level, the conditional probability P(B | A) is the mathematical formulation of our belief in the hypothesis B, given empirical evidence A.

A high P(B | A) makes B more likely to happen, given that A is observed.

A high P(B | A) makes B more likely to happen, given that A is observed.

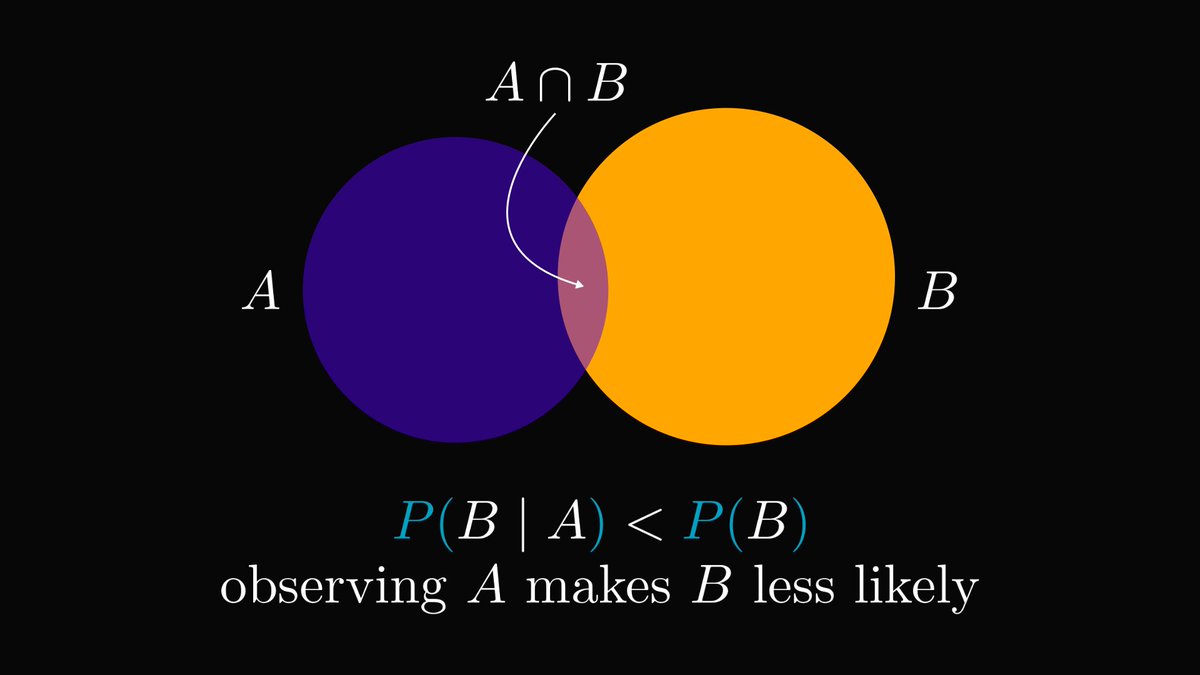

On the other hand, a low P(B | A) makes B less likely to happen when A occurs as well.

This is why probability is called the logic of science.

This is why probability is called the logic of science.

To give you a concrete example, let's go back to the one mentioned earlier: the rain and the wet sidewalk. For simplicity, denote the events by

A = "the sidewalk is wet",

B = "it's raining outside".

A = "the sidewalk is wet",

B = "it's raining outside".

The sidewalk can be wet for many reasons, say the neighbor just watered the lawn. Yet, the primary cause of a wet sidewalk is rain, so P(B | A) is close to 1.

If somebody comes in and tells you that the sidewalk is wet, it is safe to infer rain.

If somebody comes in and tells you that the sidewalk is wet, it is safe to infer rain.

Probabilistic inference like the above is the foundation of machine learning.

For instance, the output of (most) classification models is the distribution of class probabilities, given an observation.

For instance, the output of (most) classification models is the distribution of class probabilities, given an observation.

To wrap up, here is how Maxwell — the famous physicist — thinks about probability.

"The actual science of logic is conversant at present only with things either certain, impossible, or entirely doubtful, none of which (fortunately) we have to reason on."

"The actual science of logic is conversant at present only with things either certain, impossible, or entirely doubtful, none of which (fortunately) we have to reason on."

"Therefore the true logic for this world is the calculus of Probabilities, which takes account of the magnitude of the probability which is, or ought to be, in a reasonable man's mind."

(James Clerk Maxwell)

By now, you can fully understand what Maxwell meant.

(James Clerk Maxwell)

By now, you can fully understand what Maxwell meant.

If you have enjoyed this thread, share it with your friends and follow me!

I regularly post deep-dive explanations about mathematics and machine learning.

I regularly post deep-dive explanations about mathematics and machine learning.

https://twitter.com/TivadarDanka/status/1581228651772727296

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh