In 1915, the Ahmadiyya Movement published the first part of ‘The Holy Qur-ān with English Translation and Explanatory Notes’, the first Ahmadi translation to be published in a European language. #qurantranslationoftheweek

The Ahmadiyya Movement was the first Islamic group to begin translating the Qur’an into European languages, a project they initiated at the beginning of the twentieth century. Since then, the Ahmadiyya has published more than 80 translations in different languages.

The idea of translating the Qur’an into other languages is almost as old as the movement itself. As early as 1890, a year after its inception, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, the founder of the Ahmadiyya Movement, approached Muslims in India.

He asked them to provide him with financial support to write a tafsīr in Urdu and then have it translated into English, so as to promote the spread of Islam in Europe.

The idea was not implemented during Mirza Ghulam Ahmad's lifetime, but during the leadership of his son, Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmad (d. 1965), who became Caliph of the movement in 1914 at the age of 25, the Ahmadis succeeded in issuing a partial translation.

Omitting the names of the translators, the front page mentions only that the translation was published by the Anjuman-i-Taraqqi Islam under the auspices of the second caliph.

The Anjuman-i-Taraqqi Islam was a small committee established by Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmad in 1914 with the purpose of designing plans for the efficient propagation of Islam.

Sher Ali, who was the secretary of the committee, and M. Sadiq were the key figures who contributed to the publication of this translation. During the preparation of the text, the Urdu translation of the first part of the Qur’an by the second caliph served as a blueprint.

In the preface, the editors of the English translation point out that there was a need for this project as previous renditions were flawed for two reasons. Either they were produced by biased orientalist scholars who had no interest in propagating the true teachings of Islam.

Or they were written by Muslim scholars who were not proficient in English. The authors consider their translation to be particularly credible since, in their own words, every note derives its authority “from the spirit and tenor” of the Qur’an.

The editors emphasize that they have “carefully avoided all those baseless tales and unfounded stories which have grievously misled many translators.”

In other words, the editors distance themselves from prophetic stories that permeated the tafsīr literature, but which are not corroborated by the Qur’an.

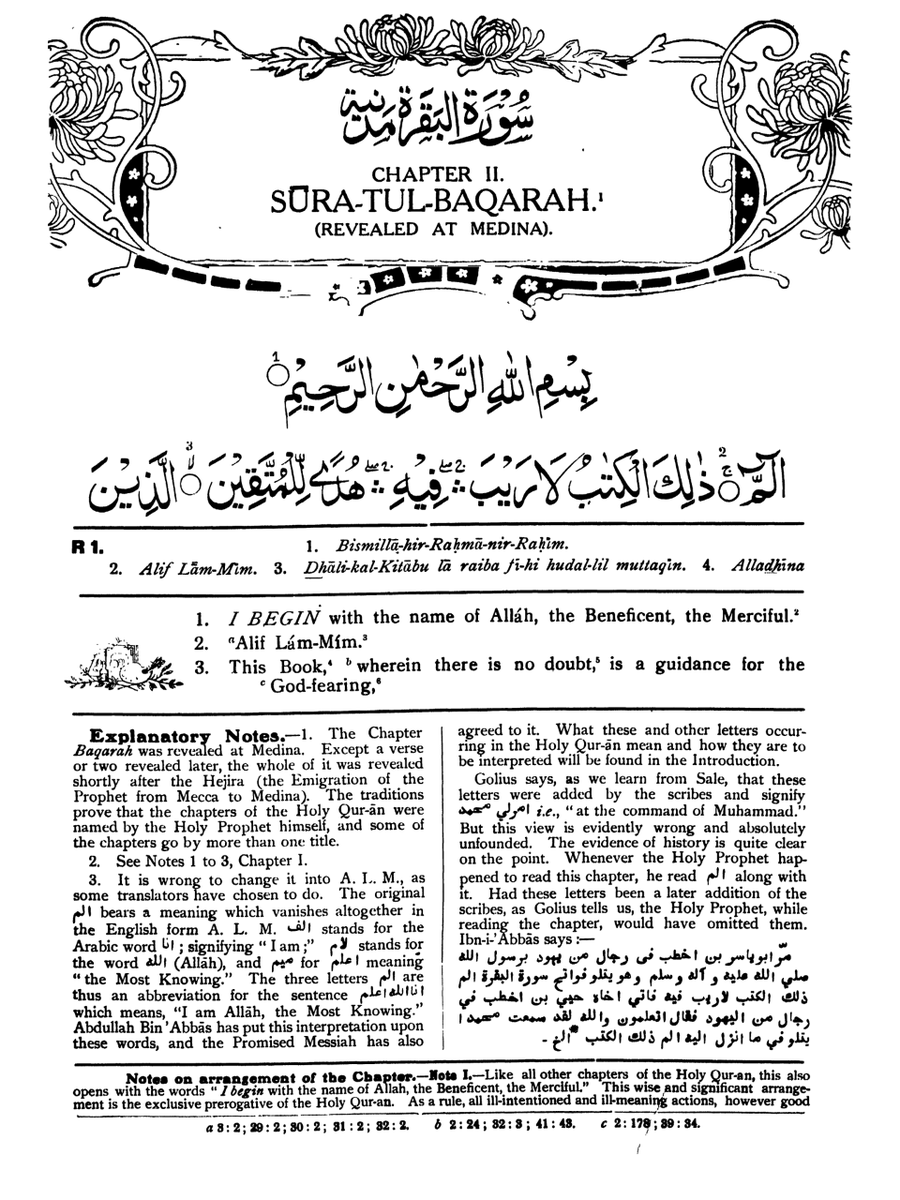

The layout of the translation has some interesting features that show that the Ahmadi project was essentially an ambitious endeavor designed to enable Western readers to study the Qur’an. Each page is divided into six sections.

First, a Qur’anic verse is provided at the top in its original Arabic wording. This is followed by a transcript of the Arabic wording in transliterated form using Latin letters. In the third section is placed the English translation of the verse.

In the final sections, there follows an interpretation of the verse, a running note on the arrangements of the Qur’anic verses and cross references.

The fact that the text included a transcription of the original wording below the Arabic script shows that this translation was not only designed for proselytizing purposes, but also to support converts who intended to learn and recite the Arabic script.

It is noteworthy that, with the exception of Surah 9, the basmala counts as the first verse of each surah. This verse counting scheme is still retained today in translations produced by the Qadian branch of the Ahmadiyya.

The translators used very extensive footnotes to comment on each verse of the Qur’an. Sometimes the views expressed in these are taken from the tafsīr literature.

For example, in Q 1:7, the Christians are identified as ‘those who have gone astray’ and the Jews as ‘those whom Thy [God’s] wrath has descended’. However, some verses testify to the fact that Ahmadi views are also clearly expressed and included in the target text.

This is very evident, for example, in the translation of Q 2:4, which reads as follows: ‘And who believe in what has been sent down to thee, and what has been sent down before thee, and firm faith have they in what is to come.’

The translation of the last part of this verse is particularly interesting since the phrase ‘wa bi l-ākhirati hum yūqinūn’ is usually translated as ‘they have firm faith in the Hereafter.’ Why did these translators opt for another choice?

They explain in a footnote that the word ‘ākhira’ bears two different meanings: first, there is a consensus in the tafsīr literature that it refers to the Day of Judgement; and secondly, it refers to the revelation which is to follow after the Qur’an.

In other words, the translators opine that, according to this verse, pious people believe in the past revelations and have firm belief in the future revelations that will come after the Qur’an.

The translators make no secret of the fact that this reference to firm belief in future revelation refers to the advent of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, the founder of the Ahmadiyya movement, who claimed to receive revelation from God.

The interpretation of this verse shows very clearly that this translation was not only designed to spread the message of Islam in the West, but also to announce the coming of the Messiah who, according to Ahmadi belief, was sent for both Christians and Muslims.

It is very clear that the translation was used as a tool to disseminate specifically Ahmadi teachings and ideas.

As this partial Ahmadi English translation was produced with the primary aim of proselytization, it was circulated in Europe and America, where this initial project by the nascent movement was welcomed, but also viewed critically.

Thus, we can read in the ‘Harvard Theological Review’ from October 1917 that, ‘With all the blind prejudice of the book, the extravagance of its

exegesis, and the preponderance of unpleasant controversy, …

exegesis, and the preponderance of unpleasant controversy, …

… it contains much genuine and deep religious feeling. The movement of which it is the outgrowth can certainly command our sympathy, and we can only wish it success in its greater aims.’

The 1915 edition contained only the Fātiḥa and half of the second surah. It is reported that the editors were convinced that they would be able to publish two or three parts serially every year. However, no subsequent part of the translation ever appeared in print.

It was not until twenty years later that Sher Ali would continue the translation, which was first published in complete form in 1955. The reasons why this initial work was not continued after 1915 are not mentioned in Ahmadi literature. #qurantranslationoftheweek ~KK~

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh