I thought it might be interesting to break down how we work with writers who are incarcerated to get this kind of story done for #CollegeInside. @opencampusmedia bit.ly/3CODrH0

First, I had to send a letter to New York with details to see if he’d be interested in doing the interview. I use an electronic mailing service where I can upload letters and background materials to save a trip to the post office. We started this in July.

Then, I had to wait for New York to call me. We couldn’t schedule a call, because his phone access is unpredictable, especially with all of the random COVID lockdowns.

If a call with a Texas area code and “Norco Conservation Camp” comes up, I know it’s from CDCR.

Calls from prison come in on weekends, sitting on a deck in Tahoe, or driving across the state.

Calls from prison come in on weekends, sitting on a deck in Tahoe, or driving across the state.

Once I talked to New York, I had to let Suave know when New York would try to call. It took a few tries of New York calling me to let Suave know when he’d be calling.

Because New York is still in San Quentin, Suave had to help organize the interview recording on his end and get the audio file to me. Phone calls are limited to 15 minutes each, so it took three calls with the “this call is being monitored and recording” in the background.

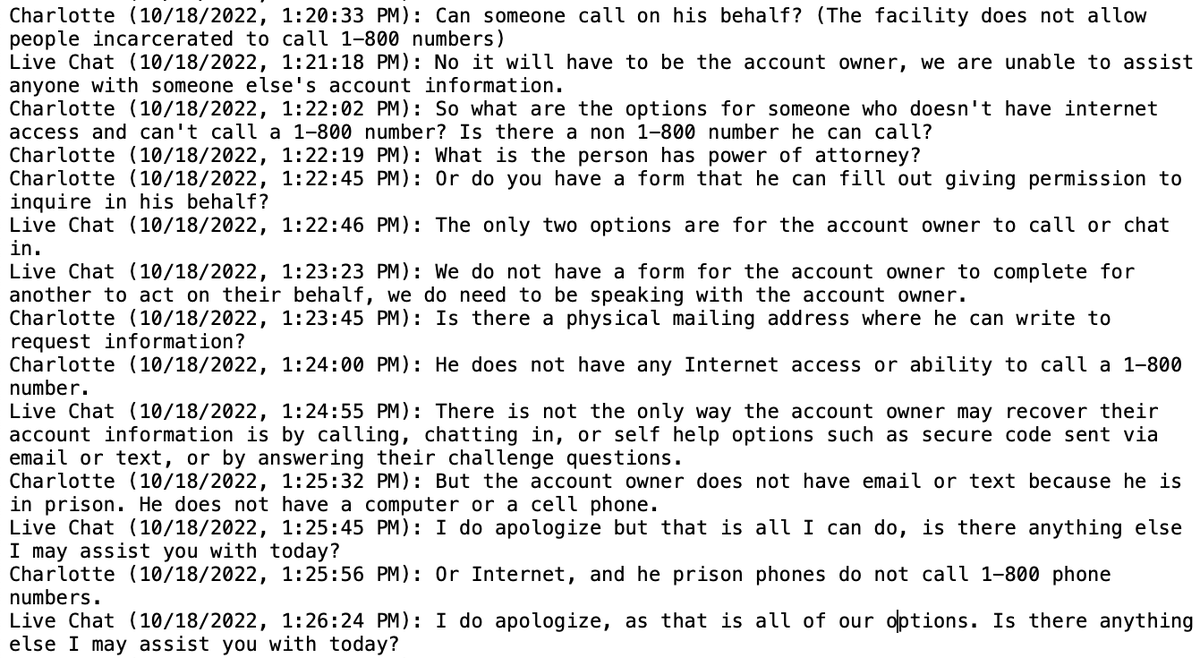

Then after I got the files of the recording, I got a transcription and sent New York a hard copy in the mail, along with some notes about what to highlight. There were a few more things we wanted to touch on, so it took arranging a follow-up call with Suave. Repeat the process.

Finally, New York sent me an edited, typewritten Q&A, which we scanned in and covered from a PDF to a word doc. The rest was a more traditional editing process, with a few quick checks on the phone.

None of these steps is especially time consuming by themselves, but this means pulling together an interview like this can stretch out over weeks. Some prisons in California have GTL tablets, but San Quentin hasn't distributed them yet so we have to rely on USPS.

So all of this is to say — the work that orgs like @prisonjourn, @empowermentave, @scalawagmag and @PENamerica are doing with inside writers takes a lot of patience and flexibility. I learned a lot from talking to them when I started this beat last year.

(Check out this quide, bit.ly/3F3jNdd, now also available as a book from @haymarketbooks) The final product is worth the process in order to get some great journalism out there. @EmilyNonko @LoveyCooper

The first draft. (Rahsaan has a typewriter, but a lot of times drafts from incarcerated writers come in handwritten)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh