European Union imports of Russian natural gas in 2022 will be down to around 60 bcm. The last time they were so low was in 1984. Here are some insights on where we go from here, using our latest @IEA #WEO2022 projections

What happens next with Russian gas is obviously uncertain, but as @tim_gould_ said at the WEO launch yesterday, we assume that there’s no way back for the EU-Russia gas relationship. That relationship was built up over many decades on the basis of trust. And that trust has gone.

In STEPS, we project a continued reduction in the EU's reliance on Russian gas. By 2030, imports are 90% lower. In APS, they are 0 before 2030. This is not easy; to avoid destructive demand reductions or price volatility, a huge scale up in clean energy (and LNG imports) needed

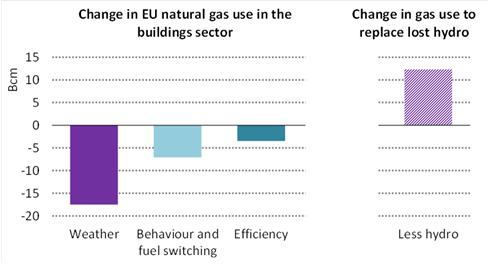

Wind and solar capacity has to increase by 600 GW by 2030. This is the major driver for a reduction in gas use in the power sector. Building retrofits accelerate and heat pumps need to be in one‐third of the EU building stock. A big dollop of hydrogen and biomethane also needed.

Europe also has to source more LNG and pipeline gas. The dilemma is whether to rely on the spot market or contract long-term supplies from either existing or new projects. Either way, anywhere from 70-170 bcm of gas needs to be bought in – even with rapidly declining gas demand.

That's a tough sell for EU gas buyers, who have huge near-term needs for more LNG but way less visibility on future demand. One way to resolve this is to shorten payback periods for new projects to 10 years (instead of 20), but this would raise the long-run cost of LNG by 20%.

Greater investment in clean energy to transition from gas is required, but this provides a big boost to energy security and ends up saving a lot of money. Cumulatively to 2050, the EU banks a $350 billion net saving compared to the STEPS, because of lower natural gas import costs

A lot of caveats come with this assessment - in practice, Russian gas can go to zero from next year. But the EU is already now pulling together the building blocks for a more resilient clean energy future.

And the loser over the long-term will be Russia. $1 trillion of lost income this decade, and no easy options to get its European gas to other consumers: in our projections, softening gas demand in China means the case for another large-scale gas pipeline is questionable, at best.

It was, as ever, a privilege to be part of the formidable #WEO team pulling together the long-term picture. Lots more gas-related stuff to unpick here (with awesome infographics!) iea.org/reports/world-…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh