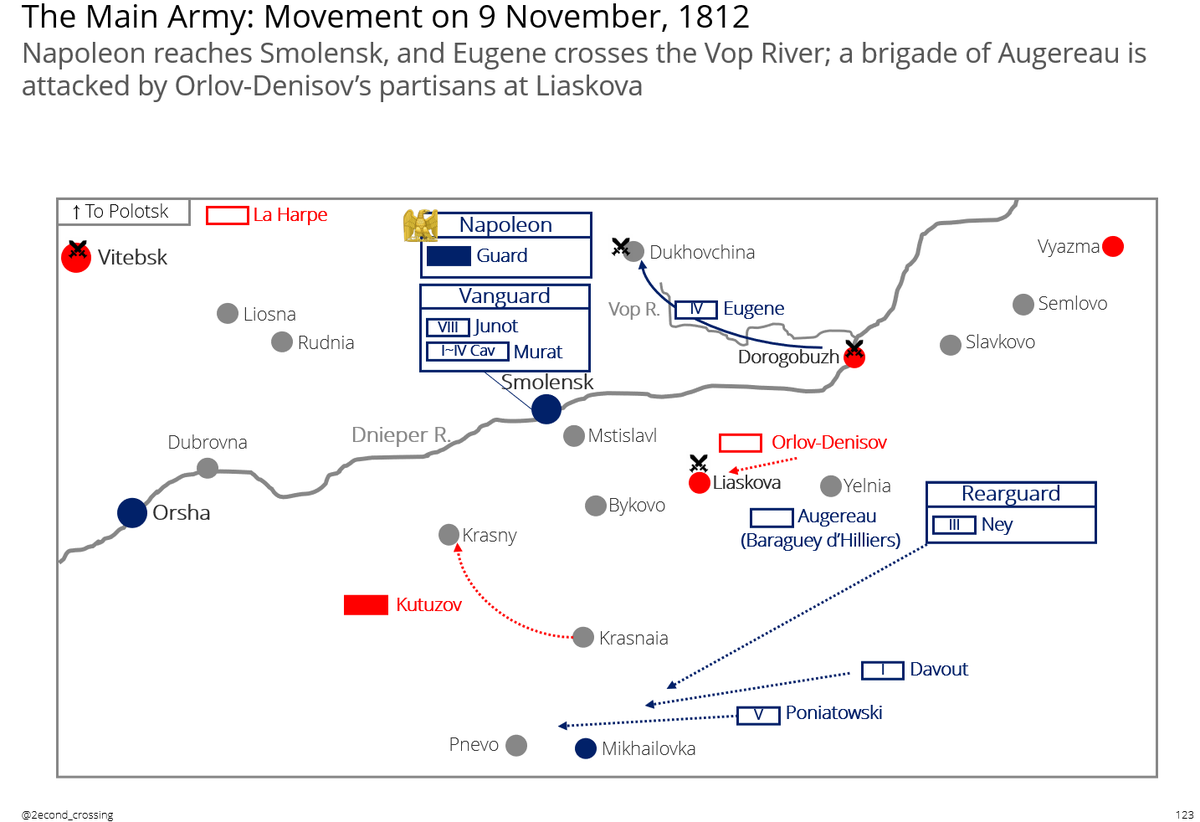

#OTD 9 November, 1812, Napoleon finally reentered Smolensk, only to become disillusioned by its derilict remains.

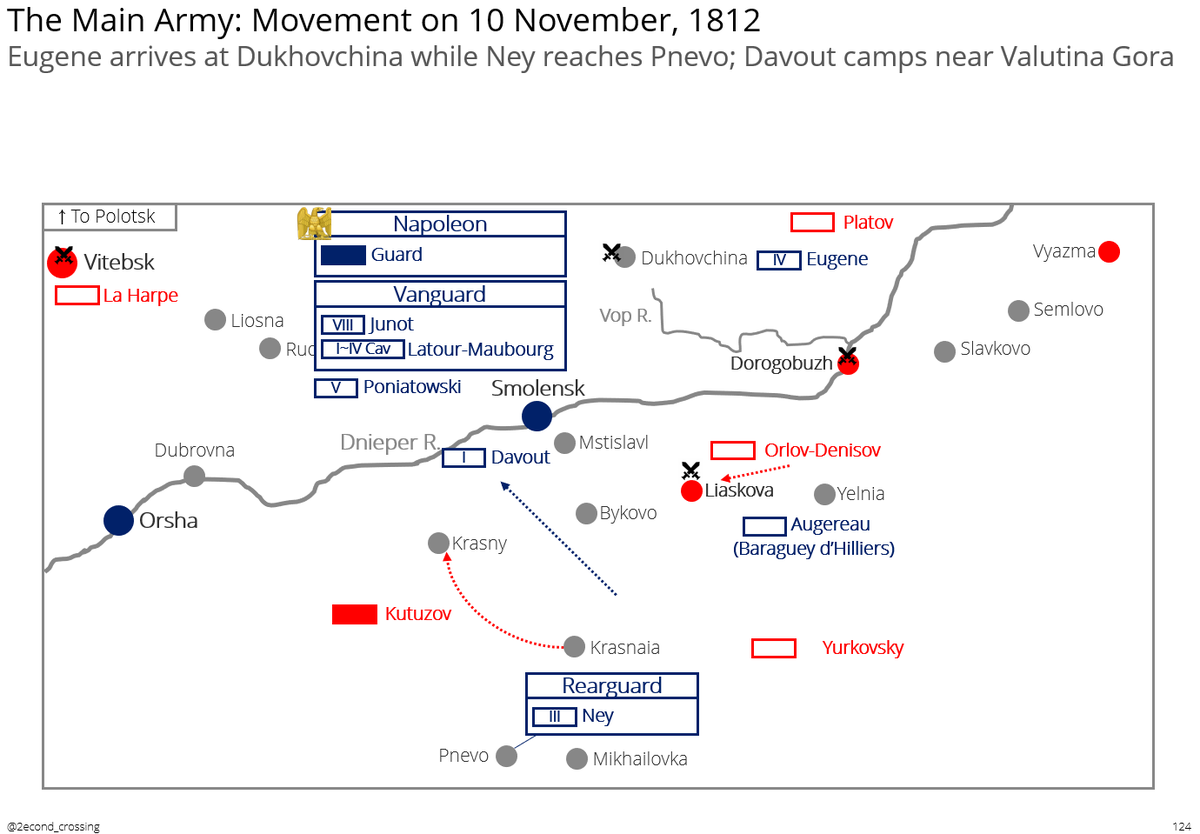

Eugene, pursued by Platov, struggled to cross the icy bank of Vop, while a brigade of Augereau was destroyed at the Battle of Liaskova.

#Voicesfrom1812

Eugene, pursued by Platov, struggled to cross the icy bank of Vop, while a brigade of Augereau was destroyed at the Battle of Liaskova.

#Voicesfrom1812

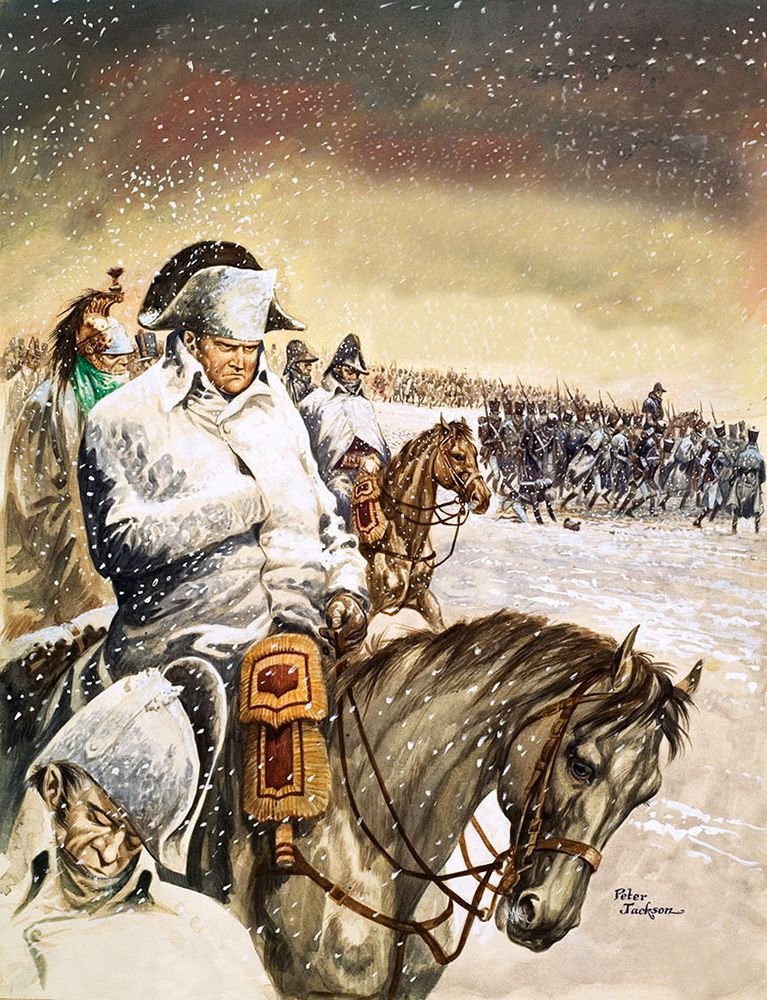

The march on Smolensk, although teeming with hope and nostalgia, was no less arduous than the previous passages.

Of the 311,200 men in the main army who had crossed the Neman, only about 45,000-14.5% of the original strength-remained functional.

Of the 311,200 men in the main army who had crossed the Neman, only about 45,000-14.5% of the original strength-remained functional.

In the morning, Bourgogne woke up to find several regiments of Hesse-Kassel, who had fallen asleep huddled together, lying still.

A three quarters of them, "along with ten thousand others from different corps," had died in their sleep. (Bourgogne)

A three quarters of them, "along with ten thousand others from different corps," had died in their sleep. (Bourgogne)

In fact, the men felt “most painful and weary” on the day of arrival, for the conscientious were obliged to carry their comrades no longer able to walk. Others only pretended to do so, while stripping away clothes and stealing money from the dying bodies. (Ibid)

The temperature plummeted to -15 degrees Celcius, forcing Napoleon to abandon his iconic greycoat for a fur-lined coat and cap. He also took to leaving his carriage several times a day to warm himself by walking, two or three times a day.

(Zamoyski, Caulaincourt)

(Zamoyski, Caulaincourt)

The Emperor travelled alongside Berthier and Caulaincourt, taking turns leaning on their arms.

All were titillated by the idea of finding solace in the winter quarter, but fell silent as they approached the battlefield near the Valutina Gora. (Caulaincourt, Bourgogne)

All were titillated by the idea of finding solace in the winter quarter, but fell silent as they approached the battlefield near the Valutina Gora. (Caulaincourt, Bourgogne)

Soldiers and officers alike wishfully envisaged Smolensk as their final destination of the year, where all of their sufferings would be brought to an end.

General Rapp expected to find "food and clothing, wherewith to defend ourselves from the pests which were consuming us."

General Rapp expected to find "food and clothing, wherewith to defend ourselves from the pests which were consuming us."

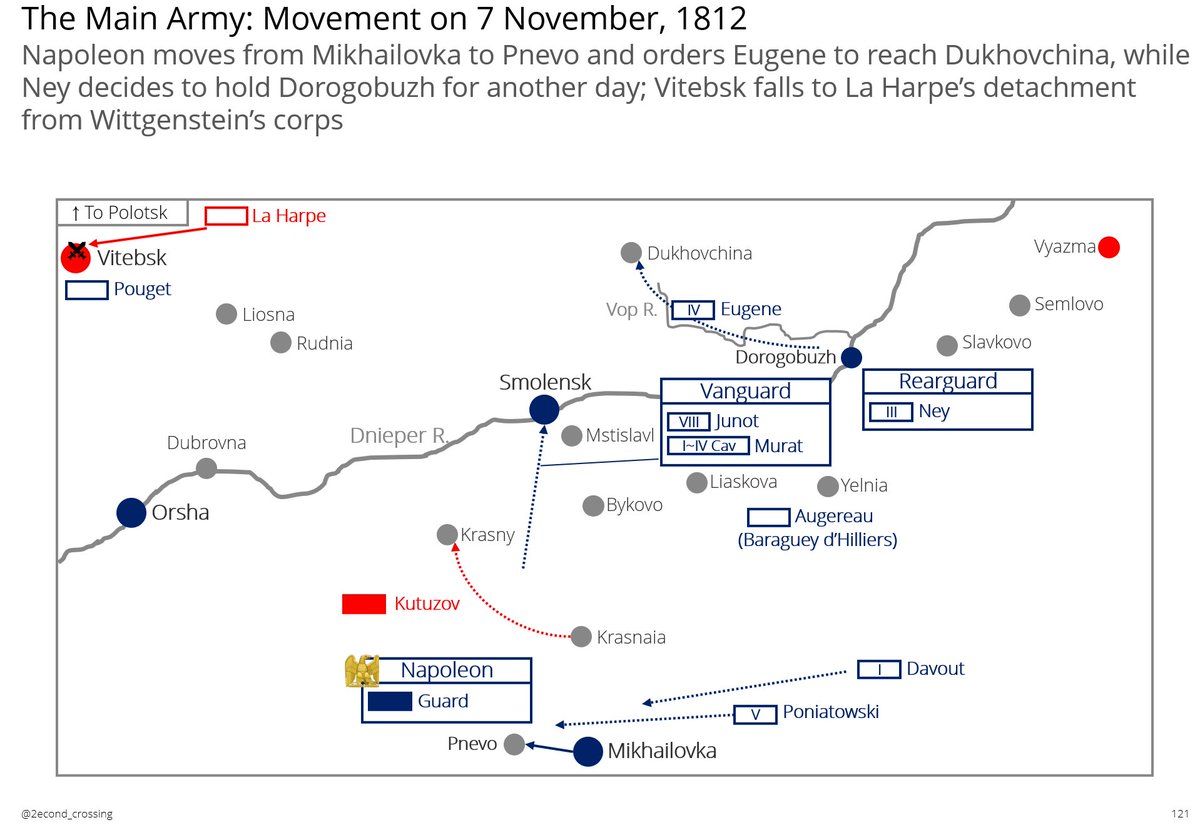

Junot's vanguard had reached the Mstislavl Gate of Smolensk on the 8th, but desisted entering after finding it in disarray. In the afternoon, Napoleon and the Guard caught a glimpse of the town which was to be their sanctuary to endure the winter.

Napoleon, like the rest, was certain that Stendhal had the warehouses of Smolensk restocked with fifteen days' ration of flour, rice, and biscuits, as he had been incessantly instructed since September.

"They expect miracles," Stendhal is said to have complained. (Zamoyski)

"They expect miracles," Stendhal is said to have complained. (Zamoyski)

Józef Załuski, one of the Poles to reach Smolensk on the 9th, imagined it to be "ready and well-stocked with all the necessary supplies," and protectd by "a permanent and strengthened rearguard." (Zaluksi)

All illusions, however, evaporated at the first glance of the city.

All illusions, however, evaporated at the first glance of the city.

The town, in fact, was only a skeletal residue of what their cannonade had devoured in August; hence, it “existed only in name.” (Bourgogne)

Their "vain hope" (Fain) was to melt away like the cloak of snow concealing the debris.

Their "vain hope" (Fain) was to melt away like the cloak of snow concealing the debris.

Those who had held onto their last hopes could not have been more delusional. The stores of Smolensk, even to the eyes of the soldiers who had forwent bread and warm shelter for five weeks, “bore no relation to…the general need.” (Caulaincourt)

"Not more than half the quantity of flour, rice, spirits," without any meat, were all they could scrap, many of which would be reserved for the Guard.(Segur)

Eustachy Sanguszko's dream of "where the abundance of promised provisions were supposed to famine was dispelled at once.

Eustachy Sanguszko's dream of "where the abundance of promised provisions were supposed to famine was dispelled at once.

The refugees who managed to remember where they had billeted in August tried to scavenge the wooden cellars. There was not a single lighting, meaning that they got lost in the first pitfall; at daylight, their bodies would be dragged out to be stripped.

"I will never forget the sight of these miserable soldiers...[who] a few weeks ago had been full of enthusiasm and energy," wrote Francis Gajewski.

Now, they were mobs "dressed bizarrely in clothes of both sexes and every trade." (Francis Gajewski)

Now, they were mobs "dressed bizarrely in clothes of both sexes and every trade." (Francis Gajewski)

Since the 8th, Napoleon had been anxious about stragglers causing “a general pillage.” Upon his entry, he declared the gates of the city shut on the unarmed and the disbanded. (Segur)

Although intended to reinstall discipline, the measure incited widespread enmity.

Although intended to reinstall discipline, the measure incited widespread enmity.

Among those at the gates, a rumor that “their entry had been delayed merely to give more rest and more provisions to this Guard” began circulating.

Others, often led by the an officer, formed their own colors and were eventually let inside the stone walls. (Ibid)

Others, often led by the an officer, formed their own colors and were eventually let inside the stone walls. (Ibid)

Napoleon, while waiting for the rear columns to arrive, issued a general order calling for reorganization of the cavalry. He assigned Latour-Maubourg to command the four corps-if one could still call it as such-, "composed of all the men available." (Correspondences)

Colonel D'Albinac, ADC to Ney, arrived to convey the disaster at Dorogobuzh: "In short-the eagles had ceased to protect-they destroyed." As soon as he got down to the gruesome details, Napoleon snapped, "Colonel, I do not ask you for these details." (Segur)

He turned to order Berthier to respond to Victor's letter from the 4th:

"His Majesty regrets to observe, that you were uncertain of the march you ought to follow. This uncertainty has already created much mischief...You mush march upon the enemy without a moment's loss."

"His Majesty regrets to observe, that you were uncertain of the march you ought to follow. This uncertainty has already created much mischief...You mush march upon the enemy without a moment's loss."

"Let us know what troops occupy Beshankovichy and Ula," he wrote, unaware that the area had been evacuated by Daendels. "The chief instruction given to you, was to defend Vilna and Minsk, which contain the stores of the army; this is an essential object," pleaded Berthier.

It was clear that the army was "no longer allow[ed]...to think of stopping at the Borysthenes." (Fain)

Metaphorically, each happenstance only signaled that "nothing could be done now but to sacrifice the army...beginning at the extremities, in order to save the head." (Segur)

Metaphorically, each happenstance only signaled that "nothing could be done now but to sacrifice the army...beginning at the extremities, in order to save the head." (Segur)

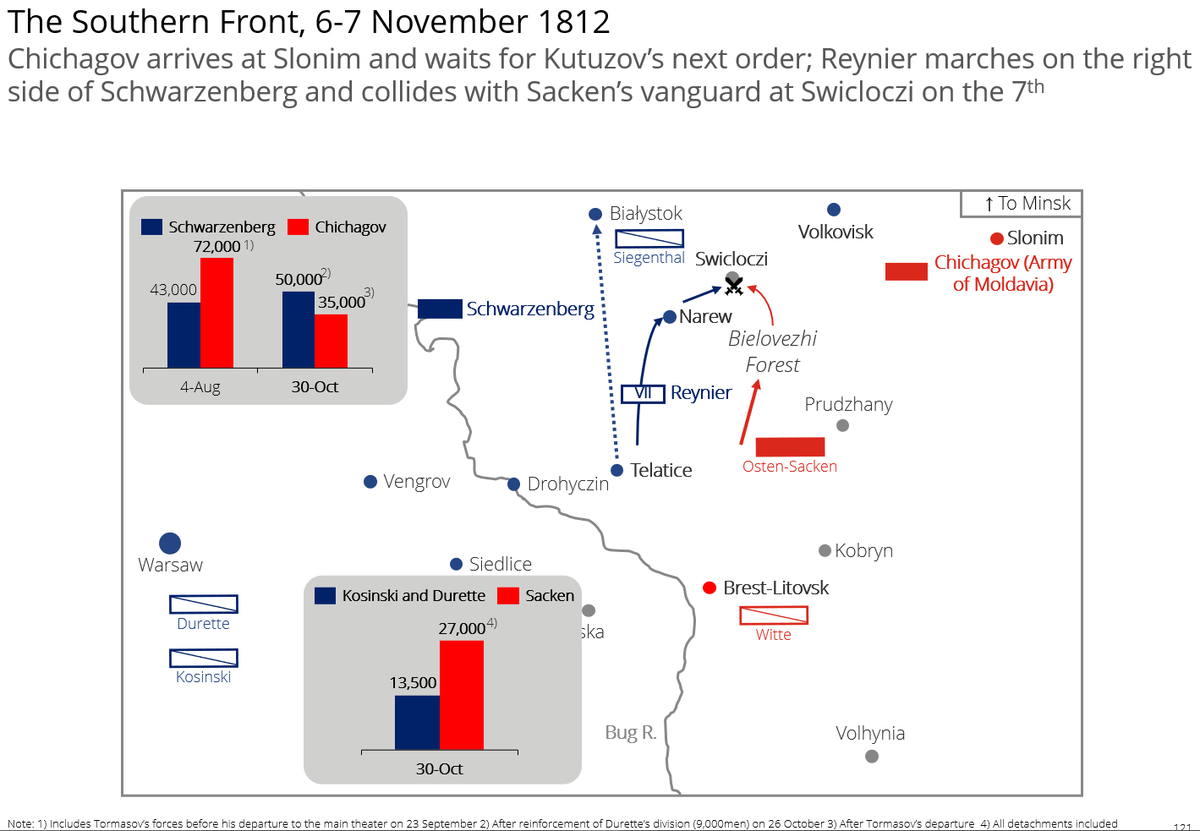

On the very day of his entry, the southern road to Smolensk was jeopardized.

The flying detachment of 3,500 partisans and Cossacks, again commanded by Orlov-Denisov, Figner, and Seslavin, assaulted the first brigade of Augereau's XI Corps, led by Baraguey d'Hilliers.

The flying detachment of 3,500 partisans and Cossacks, again commanded by Orlov-Denisov, Figner, and Seslavin, assaulted the first brigade of Augereau's XI Corps, led by Baraguey d'Hilliers.

This brigade of 2,000, commanded by Marshal Augereau's brother Jean-Pierre, had been assigned to defend the Yelnia-Smolensk road.

They attempted a futile resistance by holding onto a height near Liaskova, but resigned "despairing of succour" in face of the Russian artillery.

They attempted a futile resistance by holding onto a height near Liaskova, but resigned "despairing of succour" in face of the Russian artillery.

Some maintained that the rest of their corps was nearby, to which Denis Davydov said: "You are armed, you are French and you are in Russia. Therefore, you must keep quiet and obey!"

Afterward, all were disarmed and taken prisoners. (Wilson, Davydov)

Afterward, all were disarmed and taken prisoners. (Wilson, Davydov)

Davydov could not believe his own eyes as Figner massacered them without remorse, for he had expected the joy from the recent turn of events to have overpowered Figner's taste for vengeance. (Davydov)

Instead, he begged that his Cossacks "who had not yet been properly 'blooded'" be allowed to shoot the prisoners.

Davydov reproached him, "Alexander Samilovich, do not shatter my illusion. Let me continue to believe that magnanimity is at the heart of your gifts."

Davydov reproached him, "Alexander Samilovich, do not shatter my illusion. Let me continue to believe that magnanimity is at the heart of your gifts."

Early in the morning, Eugene's IV Corps approached the River Vop, a northern tributary of the Dnieper leading to Dukhovchina.

The "baggage train ranged up along the banks of the stream" and Platov's Cossacks hot on the heels called for an immediate crossing. (Labaume)

The "baggage train ranged up along the banks of the stream" and Platov's Cossacks hot on the heels called for an immediate crossing. (Labaume)

Eugene was devastated to find the only bridge available, constructed overnight by General Poitevin's engineers, dismantled by the flood.

The Vop, "a mere brook" during the summer, had transformed into two formidably steep defiles encompassing "rough and frozen banks." (Segur)

The Vop, "a mere brook" during the summer, had transformed into two formidably steep defiles encompassing "rough and frozen banks." (Segur)

The Cossacks, with "fresh courage at the state of [their] predicament," incessantly fired at the stranded soldiers. With a characteristic "sang-froid...invaluable in this desperate dilemma," Eugene bravely commanded the skirmishers to secure his flanks and rear. (Labaume)

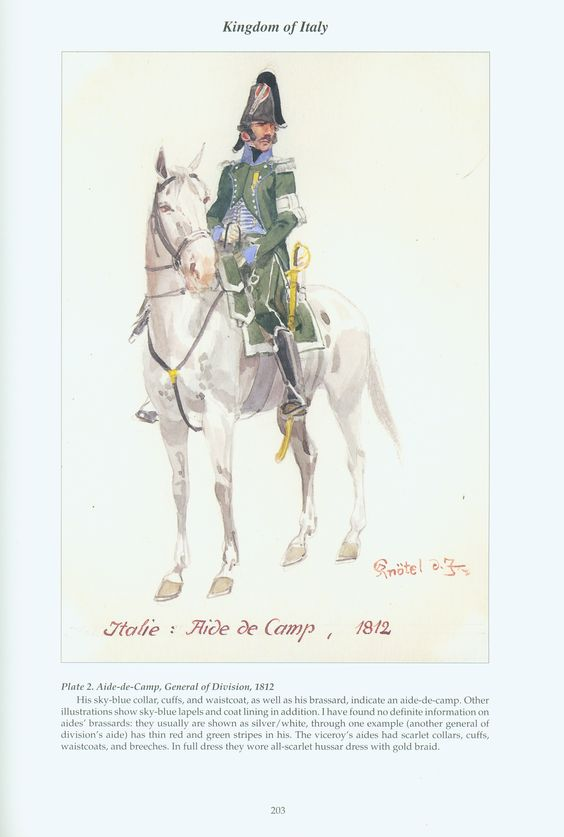

The Royal Guard, spearheaded by Eugene's ADC Bataille and his orderly officer Colonel Delfanti, made the first crossing. Eugene, then, followed.

Moved by their embodiment of valor, the whole corps threw themselves into the water "up their middle...full of floating ice." (Ibid)

Moved by their embodiment of valor, the whole corps threw themselves into the water "up their middle...full of floating ice." (Ibid)

The river was so deep that all were forced into "one place where a slope had been cut." As shallow as it

was, that point proved to muddy for the trains to pass.

And this signalled the beginning of their plight-termed 'la notte d'orrore' by the Italians.

(Labaume, Zamoyski)

was, that point proved to muddy for the trains to pass.

And this signalled the beginning of their plight-termed 'la notte d'orrore' by the Italians.

(Labaume, Zamoyski)

As each vehicle hopelessly sunk into the deep ruts, the 5,000 to 6,000 soldiers and 2,000 stragglers became dispersed over where "the water kept rising every moment." (Segur, Labaume)

Then, the Cossacks resumed their fires, fearfully concealed by a thick mist. (Thiers)

Then, the Cossacks resumed their fires, fearfully concealed by a thick mist. (Thiers)

The chaos, amplified by "the most savage cries" of the enemy, instantly dissolved Eugene's aura over his soldiers. They hastily spiked their guns and threw away their loots and even the meager amount of food they had, reducing themselves to "fugitives from Moscow." (Thiers)

The muddy, icy water became flooded with portmanteaus, carriages, caissons, and "innumerable corpses of the drowned" and their horses. (Labaume)

The survivors were across the river only by night, only to have an "entirely useless march" waiting for them. (Thiers)

The survivors were across the river only by night, only to have an "entirely useless march" waiting for them. (Thiers)

@threadreaderapp Unroll. No typo on the front page plz!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh