A thread here for those who don't understand why the China protests over the weekend protests are so shockingly rare.

Surveillance. In. China. Is. Extreme. Think you could evade Chinese police? Let's walk through it:

Surveillance. In. China. Is. Extreme. Think you could evade Chinese police? Let's walk through it:

"There's tons of people protesting, they'll never catch me," nope - Chinese police stations use huge networks of facial recognition cameras that can retroactively trace people for days or even months.

For example, this 2018 police document describing a network of thousands of cameras in a single Tianjin district that saves faces within the last 90 days, traces people over time and generates alarms for "high risk behavior" like *checks notes* being out after midnight.

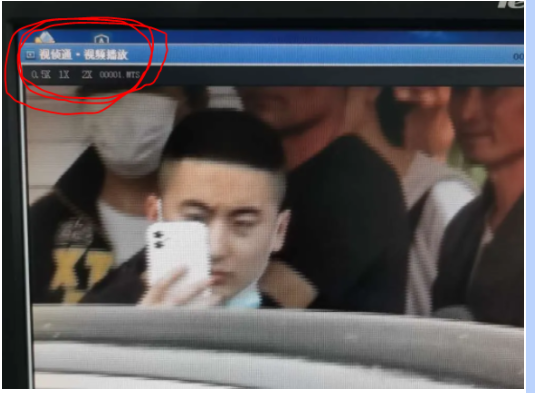

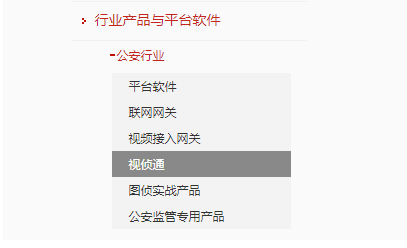

"But I'll just wear a mask or sunglasses then," nope - I've seen 1000s of procurements describing Chinese police surveillance systems over the years - most recognise people despite face coverings (and whether you have a "yellow, white, black or brown race face" - Guangxi 2019)

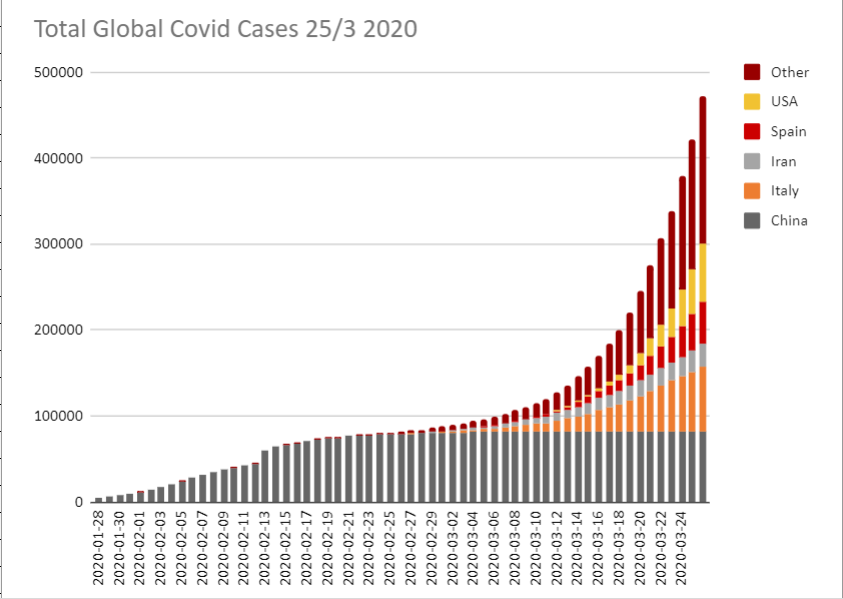

It's tough to know for sure how effective they truly are, but COVID gave us hints - like when officials in Tianjin used surveillance cameras to ID thousands near a supermarket and conduct home visits. reuters.com/article/us-hea…

“But I’m at a university, kids protest, surely it’s more relaxed?” nope – University surveillance is high, and heightened by Covid – last year I spoke to students about what it’s like to be put to bed by surveillance cameras : reuters.com/article/us-hea…

“But I only protested online” – nope, China since 2014 has steadily enforced real name registration that links your national ID via your phone number to any online service – social media companies are bound by law to comply, and police enforce it.

Example, when Wuhan residents in early 2020 went online to say that relatives were falling ill from a disease the govt had so far denied was contageous, some told me they were visited within hrs by police. In one case, police came to the hospital to order a family to remove posts

“But there’s so many people posting, they can’t see everything,” nope – virtually every city police bureau has embraced big data 舆情分析 (public opinion analysis) technology – designed to monitor dissent and filter through millions of data points to find instigators.

I wrote a bit about this system here earlier this year, and how it's increasingly covering overseas social media: washingtonpost.com/national-secur…

“But I'll just alternate apps to communicate then” nope – here a 2022 proc doc describes a standard Chinese police phone forensics kit & the apps they pull data from: over 1000 local + foreign apps from Twitter to Telgegram, Airbnb, Fitbit and Uber, which isn't even in China.

More and more frequently, police are employing mobile smartphone forensic systems on the streets, procurements show. I wrote about people’s experiences with them here: reuters.com/article/us-chi…

And as China reporters have noted - people are reportedly being stopped by police who are checking phones fore apps like Signal and Instagram, and deleting photos (an experience most China reporters in the field have also gone through at least once)

“But after all that, at least people will remember my protest” – not likely, a search on Weibo (China’s Twitter) today shows nothing is happening at all. Why? Each company has 1000s of censors. I wrote about one of these incredible censorship factories: reuters.com/article/us-chi…

“Ok, no protest then – I’ll just use the legal, government sanctioned complaints system, aka ‘petitioning’ where you can submit official grievances online and in dedicated offices across the country” – nope, not really a good idea.

Beijing champions this system as a legal way of raising grievances but using it can quickly land you on blacklists. Procurements for police surveillance systems list petitioners alongside fugitives, drug addicts, mental patients, and Uyghurs as “key personnel” that trigger alarms

For example, a Liaoning government procurement from last week outlines a new services database for military veterans – sounds great, except a major function of it is to track petitioners – including surveilling veterans so any protest won’t interfere in "major" political events.

"Ok so I'm caught holding a white piece of paper, can I even be charged for that?" yes - China has vaguely defined laws against "picking quarrels and provokling trouble” or "gathering a crowd to disrupt order", which set a low bar for charges or legal threats

A quick scan of available Chinese court records show these charges are no joke, some with long jail terms, like these people who protested the demolition of their village, inc going to Beijing to petition, and in 2020 were sentenced to 3.5 years in jail for 'gathering crowds'

A good story today from @martinpollard21 & @ParkSuAm1996 on how police are beginning to track down people involved over the weekend reuters.com/world/china/ch…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh