More car hacking!

Earlier this year, we were able to remotely unlock, start, locate, flash, and honk any remotely connected Honda, Nissan, Infiniti, and Acura vehicles, completely unauthorized, knowing only the VIN number of the car.

Here's how we found it, and how it works:

Earlier this year, we were able to remotely unlock, start, locate, flash, and honk any remotely connected Honda, Nissan, Infiniti, and Acura vehicles, completely unauthorized, knowing only the VIN number of the car.

Here's how we found it, and how it works:

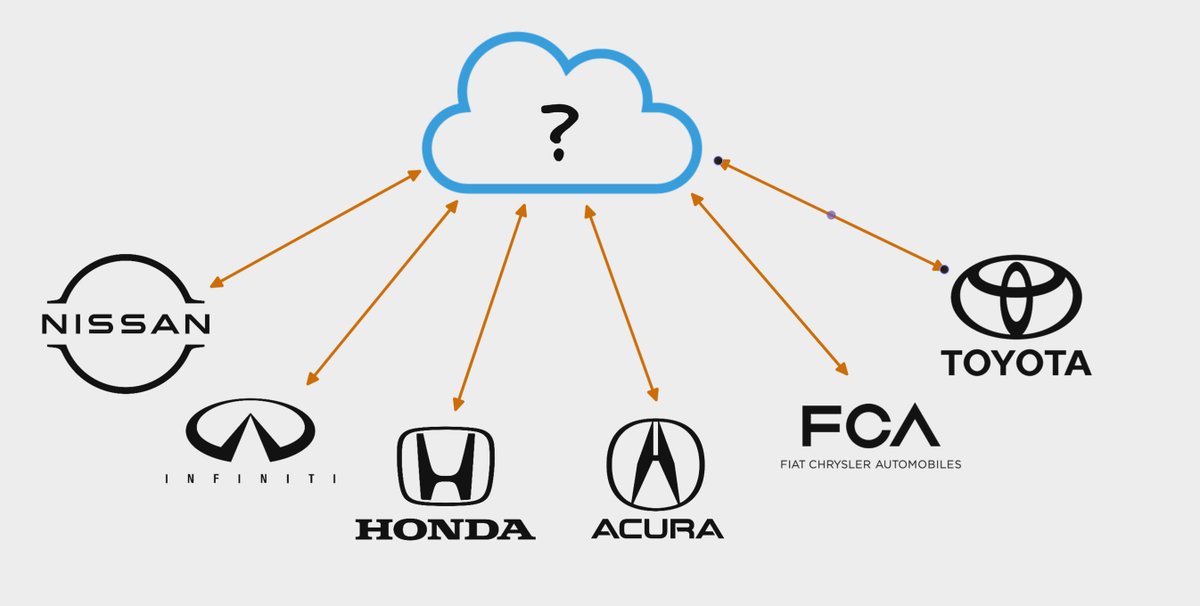

After finding individual vulnerabilities affecting different car companies, we became interested in finding out who exactly was providing the auto manufacturers telematic services.

We thought it was likely there was a company who provided multiple automakers telematic solutions.

We thought it was likely there was a company who provided multiple automakers telematic solutions.

While exploring this avenue, we kept seeing SiriusXM referenced in source code and documentation relating to vehicle telematics.

This was super interesting to us, because we didn't know SiriusXM offered any remote vehicle management functionality, but it turns out, they do!

This was super interesting to us, because we didn't know SiriusXM offered any remote vehicle management functionality, but it turns out, they do!

We found the SiriusXM Connected Vehicle website and noticed the following quote:

"[SiriusXM] is a leading provider of connected vehicles services to Acura, BMW, Honda, Hyundai, Infiniti, Jaguar, Land Rover, Lexus, Nissan, Subaru, and Toyota."

So many brands under one roof!

"[SiriusXM] is a leading provider of connected vehicles services to Acura, BMW, Honda, Hyundai, Infiniti, Jaguar, Land Rover, Lexus, Nissan, Subaru, and Toyota."

So many brands under one roof!

At this point, we kicked off scans and scoured the internet trying to find as many domains we could owned by SiriusXM, and additionally reverse engineered all of the mobile apps of SiriusXM customers to see how the remote management actually worked.

During this process, we found the domain "telematics.net" and began investigating. From what we found, it appeared to handle services for enrolling vehicles in the SiriusXM remote management functionality.

After pivoting to this domain in particular, we found a large number of references to it in the NissanConnect app and decided to dig as deep as we could.

We reached out to someone who owned a Nissan, signed into their account, then began inspecting the HTTP traffic.

We reached out to someone who owned a Nissan, signed into their account, then began inspecting the HTTP traffic.

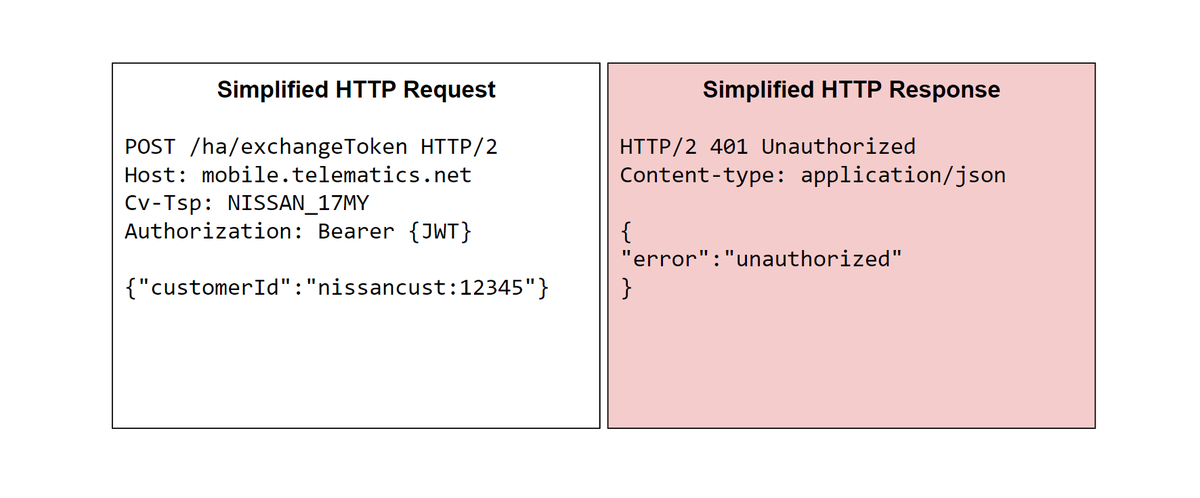

There was one HTTP request in particular that was interesting: the "exchangeToken" endpoint would return an authorization bearer dependent on the provided "customerId".

While fuzzing, we removed the "vin" parameter and it still worked. It seemed to only care about "customerId".

While fuzzing, we removed the "vin" parameter and it still worked. It seemed to only care about "customerId".

The format of the "customerId" parameter was interesting as there was a "nissancust" prefix to the identifier along with the "Cv-Tsp" header which specified "NISSAN_17MY".

When we changed either of these inputs, this request failed.

When we changed either of these inputs, this request failed.

Trying to be cheeky, we went for an obvious IDOR and changed it the "customerId" parameter to another users customer ID. This failed and gave us an authorization error.

Not entirely satisfied, we left this endpoint to rest and began looking at other endpoints.

Not entirely satisfied, we left this endpoint to rest and began looking at other endpoints.

Hours later, in one of the HTTP responses we saw the following format of a VIN number:

vin:5FNRL6H82NB044273

This vin format looked eerily similar to the "nissancust" prefix from the earlier HTTP request. What if we tried sending the VIN prefixed ID as the customerId?

vin:5FNRL6H82NB044273

This vin format looked eerily similar to the "nissancust" prefix from the earlier HTTP request. What if we tried sending the VIN prefixed ID as the customerId?

It returned "200 OK" and returned a bearer token! This was exciting, we were generating some token and it was indexing the arbitrary VIN as the identifier.

To make sure this wasn't related to our session JWT, we completely dropped the Authorization parameter and it still worked!

To make sure this wasn't related to our session JWT, we completely dropped the Authorization parameter and it still worked!

We took the authorization bearer and used it in an HTTP request to fetch the user profile. It worked!

The response contained the victim's name, phone number, address, and car details.

At this point, we made a simple python script to fetch the customer details of any VIN number.

The response contained the victim's name, phone number, address, and car details.

At this point, we made a simple python script to fetch the customer details of any VIN number.

We continued to escalate this and found the HTTP request to run vehicle commands.

This also worked!

We could execute commands on vehicles and fetch user information from the accounts by only knowing the victim's VIN number, something that was on the windshield.

This also worked!

We could execute commands on vehicles and fetch user information from the accounts by only knowing the victim's VIN number, something that was on the windshield.

At this point, we identified that it was also possible to access customer information and run vehicle commands on Honda, Infiniti, and Acura vehicles in addition to Nissan.

We reported the issue to SiriusXM who fixed it immediately and validated their patch.

We reported the issue to SiriusXM who fixed it immediately and validated their patch.

Thank you for reading, huge shout out to all of these amazing people for helping with this research:

@_specters_ @bbuerhaus @d0nutptr @xEHLE_ @iangcarroll @sshell_ @infosec_au!

We hope to publish more security findings over our few months spent researching this topic soon.

@_specters_ @bbuerhaus @d0nutptr @xEHLE_ @iangcarroll @sshell_ @infosec_au!

We hope to publish more security findings over our few months spent researching this topic soon.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh