#OTD 9 December, 1812, the greater part of the Grande Armée arrived at Vilna, only to realize that this would not be the end of the excruciating journey. Instead, they found themselves twice betrayed by the commanders-first by Napoleon, then by Murat.

#Voicesfrom1812

#Voicesfrom1812

At daybreak, only 140 men of the IV Corps at Rudnicki rose up at the drum roll. The remainder of Davout, Maison, Ney, Eugene, and Victor's corps, as well as stragglers from various units, moved out of this "miserable village" with utmost haste. (Labaume)

The exactly same phenomenon was taking place at Vilna; no one could, or would, muster himself to wake up and show up to the town's square.

Some, like Brandt, woke up "a new man"; dressed in a new linen, clean-shaven, and replenished. (Brandt)

Some, like Brandt, woke up "a new man"; dressed in a new linen, clean-shaven, and replenished. (Brandt)

But others became intoxicated by the newfound comfort. Major Boulart of the Guard Artillery wrote how a proper meal had rendered him "so stupefied" with "an urgent longing for sleep." He refused to leave his billets and neglected to tend for his horses and servants. (Austin)

On the 8th, Berthier had specifically instructed Ney to merge forces with Wrede's detachment near Rudnicki. Napoleon had estimated them to be about 12,000 men in total.

Soon, those Bavarian soldiers ran into Eugene's men, "crying that the enemy were at their heels." (Labaume)

Soon, those Bavarian soldiers ran into Eugene's men, "crying that the enemy were at their heels." (Labaume)

That figure had taken into account all the reinforcements made at Glubokoye. As of now, the Bavarians numbered only 2,500 with barely any horse healthy enough to hold a few guns. Even their commander looked disquietingly unstable.

(Rapp, Clausewitz, Labaume, Chłapowski)

(Rapp, Clausewitz, Labaume, Chłapowski)

Like those who had reached Vilna on a day ago, the second line of sojourners were ferociously pursued by the Cossacks and the cold, still -27 to 28°C. (Segur)

"So intense was the cold," wrote Marbot, "that we could see a kind of vapor rising from men's ears and eyes."

"So intense was the cold," wrote Marbot, "that we could see a kind of vapor rising from men's ears and eyes."

When those vapors froze hard in the air, they fell back on men and horses "with a rattle such as grains of millet might have made."

The cavalry were forced to halt every now and then to "clear away from the horses' bits the icicles formed by their frozen breath." (Marbot)

The cavalry were forced to halt every now and then to "clear away from the horses' bits the icicles formed by their frozen breath." (Marbot)

Another source of nuisance was the Cossacks, who had "placed light guns on sledges" and made some "partial attacks." (M.)

Among them, Davydov's sledge "kept bumping against heads, legs, and arms of men who had frozen to death, or were close to dying." (Davydov)

Among them, Davydov's sledge "kept bumping against heads, legs, and arms of men who had frozen to death, or were close to dying." (Davydov)

Scarcity bred discontents, forcing the army of twenty tongues onto the Babel.

Captain Rudnicki, after much begging, bought from a French dragoon some boiled potatoes for a Napoleon d'or.

He bitterly wrote that "the French were greedy for money, much like our Jews."

Captain Rudnicki, after much begging, bought from a French dragoon some boiled potatoes for a Napoleon d'or.

He bitterly wrote that "the French were greedy for money, much like our Jews."

On the contrary, Marbot accused the Poles, whom he called "the new enemies for us", of stealing from the French:

"Saxe, the son of one of their own kings, said rightly that the Poles are the greatest plunderers in the world, and would not respect even their fathers' goods."

"Saxe, the son of one of their own kings, said rightly that the Poles are the greatest plunderers in the world, and would not respect even their fathers' goods."

When a group of (bored) Polish soldiers kept on shouting "Hourra!" at the French and the Swedes, Maison resolved to take serious action. He declared that "it was neither the place nor the time for joking," and had all of those "sham Cossacks" shot. (Marbot)

Such were the prevailing sentiments on the last three miles before Vilna, as Labaume described:

"Our hearts grew so callous that these terrible tragedies ceased to affect us, and a brutal selfishness reigned supreme in the state of abasement to which we had been reduced."

"Our hearts grew so callous that these terrible tragedies ceased to affect us, and a brutal selfishness reigned supreme in the state of abasement to which we had been reduced."

And yet, never did the idea of a town evoke so much hopes; serving as the sole raison d'etre for the fugitives. In the absence of Napoleon, "Vilna! Vilna!" was the "word which was identified in the minds of the troops with the ideas of repose, security, and abundance." (Thiers)

In this "last state of physical and moral distress," the greater half of the army reached Vilna; or, more precisely, they stumbled into a disconcerting "mass of men, horses, and chariots, motionless, and deprived of the power of movement." (Segur)

While making his way through the congested road, Bourgogne lost "a little box containing rings, hair necklaces, and portraits of the mistresses [he] had had" from all the countries."

He "recognized the village for the same" as "five months before."

He "recognized the village for the same" as "five months before."

To the pilgrims' dismay, there was no singular authority to reinstill any trace of order. Both Maret and Hogendorp had retired to the Neman, while Murat remained at a loss what to do, when even his ADCs were being ignored by the subordinate officers. (Marbot, Fezensac)

As a result, the debris of abandoned vehicles from the previous day had not been cleared off. Meanwhile, the fortunate ones who had managed to slip in found the the local commisaries struggling endlessly to distribute food and billets to each regiment. (Marbot)

Up to now, the men had envisaged Vilna to be the endpoint of their sojourn.

"And yet Vilna, the object of our fondest hopes...was destined to be for us another Smolensk!...The confusion was so terrible that it reminded me of the passage of the Berezina," Labaume wrote.

"And yet Vilna, the object of our fondest hopes...was destined to be for us another Smolensk!...The confusion was so terrible that it reminded me of the passage of the Berezina," Labaume wrote.

Once the men were inside the town, they could not be more disillusioned, for the "scene of confusion was repeated in its streets." (Thiers)

The placards indicating each billet and place of provision, placed by Hogendorp on the previous day, were nowhere to be seen.

The placards indicating each billet and place of provision, placed by Hogendorp on the previous day, were nowhere to be seen.

Nor was there a smooth distribution of flour, bread, and meat from the magazines. As in Smolensk, the commisaires ordered that priority be given to formed troops, "a thing which, in the disorganized state of all the regiments, was impossible to do." (Marbot)

The administrators, either "afraid of being made responsible" or "dread[ing] the excesses to which the famished soldiers would give themselves up," simply shunned them.

Against their "most unseasonable formalities," Marbot had one of the magazines smashed open. (Segur, Marbot)

Against their "most unseasonable formalities," Marbot had one of the magazines smashed open. (Segur, Marbot)

Again left on their own to survive, "the ragged, starving soldiers" went roaming around the dainty houses in Vilna.

Some "paid gold for the meanest food," while others "sought a piece of bread from the charity of the inhabitants." (Fezensac)

Some "paid gold for the meanest food," while others "sought a piece of bread from the charity of the inhabitants." (Fezensac)

Lejeune witnessed how the residents initially "received us kindly...full of hospitality and pity for our sufferings."

Everything changed once "fresh crowds of starving, debilitated wretched arrived," who stormed every shop, inn, and cafe within their sight. (Lejeune)

Everything changed once "fresh crowds of starving, debilitated wretched arrived," who stormed every shop, inn, and cafe within their sight. (Lejeune)

The shopkeepers, "unable to keep the enormous mob of customers, promptly put up their shutters," wrote Labaume. Then they automatically turned to pillaging:

"But goaded by hunger and resolved not to starve to death, we smashed in the doors..." (Labaume)

(Continued/Replies)

"But goaded by hunger and resolved not to starve to death, we smashed in the doors..." (Labaume)

(Continued/Replies)

Those who had spent the previous night at Vilna did not come to their aid, for most of them simply had not expected to face the same set of difficulties here.

To cite Adrian de Mailly-Nesle, "rest, bread, Vilna had come to form a trinity...a single hope."

To cite Adrian de Mailly-Nesle, "rest, bread, Vilna had come to form a trinity...a single hope."

"...[A]s a result we were clear in our minds that we would go no further than this city," wrote the young officer. (Zamoyski)

Yet, it was becoming increasingly clear that they could not hold onto Vilna for an extended period of time.

Yet, it was becoming increasingly clear that they could not hold onto Vilna for an extended period of time.

Among the crowd thronging the streets of Vilna, Baron Dezydery Chłapowski of the 1st Chevau-légers was approached by a disheveled-looking man. It happened to be Wrede, who embodied “the demoralization…among the soldiers from the Confederation of the Rhine.“

“I met a man wearing a civilian coat, a sort of turban on his head, and who carried a sword, but had no gloves. In addition, he was running, followed by about 15 soldiers armed with muskets and presenting their bayonets as if about to charge,” he wrote. (Chłapowski)

Wrede, whose face was “swathed in handkerchiefs, was the first to recognize the other by his Czapka. He angrily demanded to know:

“Where is headquarters? [The Cossacks] are capturing men in the streets, and the Imperial Guard has not left their quarters!”

“Where is headquarters? [The Cossacks] are capturing men in the streets, and the Imperial Guard has not left their quarters!”

Only then Chłapowski recognized that familiar voice from 1809. He quietly offered to escort him there, since he too was on his way to see Murat. Before going together, he had to make one final request:

“General…sheath your sword or you will alarm King Murat..”

(Chłapowski)

“General…sheath your sword or you will alarm King Murat..”

(Chłapowski)

While Chłapowski listlessly tried to calm down Wrede, assuring him that no Cossack was nearby, Captain Józef Szymanowski of the 2nd Regiment saw witnessed an extremely bizarre scene, when "the horses pulling an imperial wagon laden with casks of gold" fell down. (Szymanowski)

The chief paymaster, having given up pushing the wagon all the way to the town, generously allowed everyone to take "as much as he could carry away" before the enemy seizes the treasure.

Just at that moment, the Cossacks arrived, who paid no attention to the Frenchmen.

Just at that moment, the Cossacks arrived, who paid no attention to the Frenchmen.

The intruders, "more greedy for money than for prisoners...began to help [them] take the gold out." Szymanowski could not believe this "strange and amusing sight" of "a French grenadier side by side with a Cossack, together emptying the wagon of the imperial treasury."

As ludicrous as that incident was, it served as a prelude to the renewal of their trials and tribulations.

At 3 p.m., the troops in the rear reported "that the Cossacks had taken possession of the heights commanding the town." (Labaume)

At 3 p.m., the troops in the rear reported "that the Cossacks had taken possession of the heights commanding the town." (Labaume)

The refugees, too used to such ambushes, remained mostly aloof; expecting 5,000 men of Loison, supported by some few hundreds of the Young Guard, to drive them away. (Berth.)

Only the cannonade, which began around 4 to 5 p.m. sparked shouts of "Cossacks!" (Dumonceau)

Only the cannonade, which began around 4 to 5 p.m. sparked shouts of "Cossacks!" (Dumonceau)

The noise penetrated the council of war in Murat's headquarter, where the marshals began to contemplate evacuating Vilna.

Ney declared that "[The retreat] is forced on us: there are no means of stopping a day longer."

Just at that moment, the cannonade was heard. (Rapp)

Ney declared that "[The retreat] is forced on us: there are no means of stopping a day longer."

Just at that moment, the cannonade was heard. (Rapp)

Segur described the grisly twist of fate:

"How delicious did a loaf of leavened bread appear to them, and how inexpressible the pleasure of eating it seated!

...But scarcely had they begun to taste these sweets, when the cannon...commenced thundering over their heads..."

"How delicious did a loaf of leavened bread appear to them, and how inexpressible the pleasure of eating it seated!

...But scarcely had they begun to taste these sweets, when the cannon...commenced thundering over their heads..."

This time, the enemy was spearheaded by General Lastrin of Chichagov's army, who had reunited with Seslavin near the suburb of Rukoni. Their "battery of twelve guns placed on sledges" enabled them to move and pour their fire in every requisite direction."

(Chichagov, Wilson)

(Chichagov, Wilson)

The campaign, which many had assumed to be over, seemed to start anew. At once, Lefebvre and other generals galloped around shouting, "To arms!"

Only the Old Guard, "which alone was still in good order, formed in the square," while others pleaded to be left alone. (Fezensac)

Only the Old Guard, "which alone was still in good order, formed in the square," while others pleaded to be left alone. (Fezensac)

Just a day ago, the marshals had entertained the idea of holding onto Vilna with the force at hand; now, seeing with their own eyes how the army had broken down irretrievably, Ney declared it "impossible to do anything with out troops." (Rapp)

The sudden return of Wrede from Rukoni served to confirm the prevailing view.

He urgently reported that "the enemy were close at his heels! the Bavarians had been driven back into Vilna, which they could no longer defend..." (Segur, Rapp)

He urgently reported that "the enemy were close at his heels! the Bavarians had been driven back into Vilna, which they could no longer defend..." (Segur, Rapp)

All realized that they no longer had any choice to make. But Murat, without issuing a proper set of orders, galloped off at 5 a.m. toward the Neman suburb, obliging Eugene and Berthier to follow helplessly. (Rosetti)

He declared that they would be heading for Kovno.

He declared that they would be heading for Kovno.

To Rapp, who was told to return to Danzig immediately, Murat uttered his words of farewell:

"I'm not going to be taken here in this piss-pot of a place."

(Austin, Zamoyski)

"I'm not going to be taken here in this piss-pot of a place."

(Austin, Zamoyski)

Murat's reaction, lacking both communication and a clear plan, exemplified Caulaincourt's every reason against giving him the supreme command. Berthezene criticized his "inconceivable absence of mind" in leaving important documents behind and not informing Mortier of his leave.

The resulting shock on the army was comparable to that following Napoleon's departure; or arguably more severe, as "the invulnerable Murat, who seemed proof against every weapon," had become the first to run away at the first cannonade. (Thiers)

Labaume's criticism of Murat was no less scathing:

"The King of Naples, throwing his dignity to the winds, bolted from his palace and, followed by his officers, fled on foot through the mob to establish himself outside the town on the road to Kovno."

"The King of Naples, throwing his dignity to the winds, bolted from his palace and, followed by his officers, fled on foot through the mob to establish himself outside the town on the road to Kovno."

At night, the marshals halted on the road to Kovno, where Berthier drafted his final orders for the commanders whose position had lost strategic significance: Schwarzenberg and Macdonald.

They were to withdraw respectively to Warsaw and Tilsit, as slowly as possible.

They were to withdraw respectively to Warsaw and Tilsit, as slowly as possible.

Countess Tisenhaus, who had received empty reassurances from Murat's secretary "that the town would be defended," anxiously observed the stragglers still "scattered among the flames" at Town Hall Square;

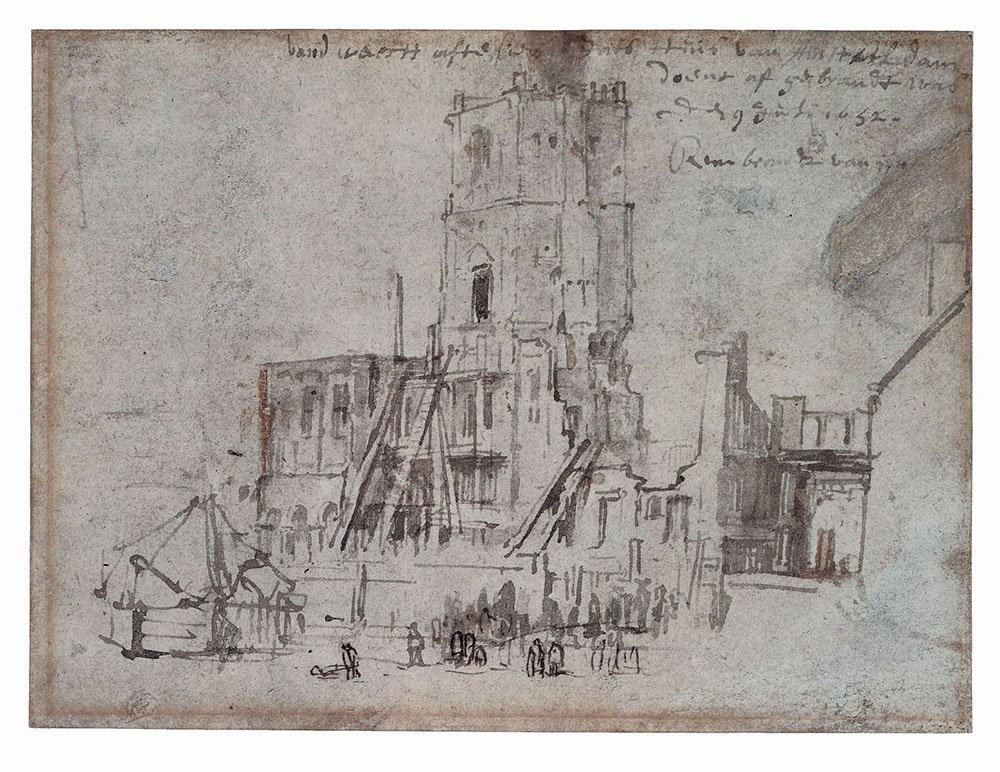

"The effect of the night added a touch of Rembrandt to it," she wrote.

"The effect of the night added a touch of Rembrandt to it," she wrote.

St. Petersburg, meanwhile, was riddled with two contradictory information: Chichagov's bulletin admitting that Napoleon had escaped, and a rumor, reflective of the locals' disappointment, that "Bonaparte was killed." (John Quincy Adams)

@threadreaderapp Unroll / 50 Threads

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh