#OTD 13 December, 1812, the tattered fragments of the Grande Armée crossed the River Neman again-utterly bereft of its splendor half a year ago.

Only Ney, with his rearguard of barely thousand men, remained behind to defend Kovno before the last crossing.

#Voicesfrom1812

Only Ney, with his rearguard of barely thousand men, remained behind to defend Kovno before the last crossing.

#Voicesfrom1812

At 2 a.m., the 85th Regiment was awakened by a familiar, avuncular voice:

"Come on, my dear Jacquet, for the last time on Russian soil, let's go see what's wanted of us."

It was the sound of old Le Roy shaking his 'bosom friend,' Lieutenant Jacquet.

(Austin)

"Come on, my dear Jacquet, for the last time on Russian soil, let's go see what's wanted of us."

It was the sound of old Le Roy shaking his 'bosom friend,' Lieutenant Jacquet.

(Austin)

Bourgogne, who had made his will to his friends and fallen unconscious, felt a "shower of hail." He recollected the very moment:

"If...I had had not my friends' help, I should very probably, like so many others, have finished my life's journey on that last day in Russia."

"If...I had had not my friends' help, I should very probably, like so many others, have finished my life's journey on that last day in Russia."

The Young Guard, encamped ten leagues away from Kovno, had to hurry up before the first daylight.

"On this march there was more readiness to help one another than before," for the thought of returning home resuscitated each man's morale to no end.

"On this march there was more readiness to help one another than before," for the thought of returning home resuscitated each man's morale to no end.

As they ascended "a sheet of ice," cries broke out from everywhere-"Stop! There is a man fallen!"

At this scene, a sergeant-major roared,

"Stop, there! I swear that not one of you shall go on until the two left behind have been picked up and brought on."

At this scene, a sergeant-major roared,

"Stop, there! I swear that not one of you shall go on until the two left behind have been picked up and brought on."

Their rekindled solidarity was attested by the fact that no one had been marked as missing during the previous roll-call.

As the road steepened and narrowed, Bourgogne kept on sliding, falling, and bruising his body already suffering enough from colic pain.

As the road steepened and narrowed, Bourgogne kept on sliding, falling, and bruising his body already suffering enough from colic pain.

Bourgogne was able to forget his wretched state by chattering endlessly with Faloppa, an old friend he had met in Spain. This mischievous man from Piedmont had managed to steal a lard at St. Hiliaume when the whole town kept their doors shut to the French.

As the men prepared a soup with these "goose-dripping" chunk of a fat, its owner, the town's executioner, came out to meet them.

He gleefully told them that it is not some fat, but "manteca de ladron"-"the fat of hanged men, which he sold for ointment."

He gleefully told them that it is not some fat, but "manteca de ladron"-"the fat of hanged men, which he sold for ointment."

For hours they had marched when the two saw "10,000 stragglers spreading in disorder," followed by "several groups of forty or fifty men, more or less composed of the officers, NCOs, and some men, carrying in the midst of them the regimental eagle."

Were they the Sacred-or Doomed, as Bourgogne dubbed-Squadron? They nonetheless seemed "proud to have been so far able to keep and guard this sacred trust," wrote Bourgogne.

The day still has not dawned when Roguet's division found itself in the vicinity of Kovno.

The day still has not dawned when Roguet's division found itself in the vicinity of Kovno.

Faloppa, who had been shrieking that he could no longer go on, was left to the mercy of some German peasants.

The nearer the men got to the town, the louder became "the roar of the distant artillery and the howling of the wind...mingled with the cries of men dying on the snow."

The nearer the men got to the town, the louder became "the roar of the distant artillery and the howling of the wind...mingled with the cries of men dying on the snow."

“Come, children of France! It must never be said that we went faster at the sound of artillery. Right about face!” Someone shouted.

The time of departure was fixed at 5 a.m., but the Guard was to halt at Wirballen and wait for Ney until the next day.

(B., F., Berthezene)

The time of departure was fixed at 5 a.m., but the Guard was to halt at Wirballen and wait for Ney until the next day.

(B., F., Berthezene)

Napoleon and Caulaincourt were thawing their hands after “one of the most painful nights on the whole journey.”

Crammed inside “a Prussian post-house,” even the patient one grew irritated about “the habitual slowness of Prussian postmasters” combined with their nonchalance.

Crammed inside “a Prussian post-house,” even the patient one grew irritated about “the habitual slowness of Prussian postmasters” combined with their nonchalance.

“For my own part, it was thirty-six hours before I was warm again,” he complained.

But as soon as their courier appeared, the sledge began broke down into the snow. The two “took advantage of this delay to have a breakfast” at an inn on the Bobr, near Silesia.

But as soon as their courier appeared, the sledge began broke down into the snow. The two “took advantage of this delay to have a breakfast” at an inn on the Bobr, near Silesia.

Napoleon avidly asked the innkeeper about “the state of the country, taxation, the administration, and what they thought of the war,” with Caulaincourt translating for both parties.

The kindhearted man, taking them for “simple travellers,” answered with “the utmost candor.”

The kindhearted man, taking them for “simple travellers,” answered with “the utmost candor.”

He was so pleased with such display of integrity that he was not irked in the slightest when a woman selling glass beads intruded into the room. Instead, he bought from her a plenty of “necklaces, rings, et cetera” and gave half of them to Caulaincourt, saying:

"I will take them to Marie Louise as a souvenir of my journey…You must give some to the lady of your heart. Never had man such a long tete-a-tete with his sovereign as you have had. This journey will be a historic memory for your family.”

As they hopped onto the small carriage-or a giant sledge-, Napoleon’s mood began to relax and soften, perhaps a bit too much.

In a blink of eye, Napoleon-once an avid learner of mathematics, estimated the maximum number of troops he could draw from France and its satellites:

In a blink of eye, Napoleon-once an avid learner of mathematics, estimated the maximum number of troops he could draw from France and its satellites:

“My cohorts make an army of more than a 100,000 men, well-disciplined soldiers led by war-trained officers. I have the money and arms form excellent cadres, and before three months have passed I shall have conscripts and 500,000 men under arms on the banks of the Rhine.“

Caulaincourt knew all too well that these figures rested on his grandiose assumptions-that Austria would remain loyal to him, thus discouraging any irridentist movements beyond the Rhine, and that additional levies would trigger no discontent in the Parisian salons.

Such complacence seeped into his imaginations about where his army was. Napoleon insisted that they must have secured Vilna.

Caulaincourt, using the Emperor’s own words, made him silent for a second:

"If there are no ‘Polish Cossacks’ there can be no rest for your army,"

Caulaincourt, using the Emperor’s own words, made him silent for a second:

"If there are no ‘Polish Cossacks’ there can be no rest for your army,"

Inside the palisades of Kovno, it was apparent that the fatal revelry has not abated a bit since the previous night.

“Many were intoxicated, and fell asleep on the snow, to wake no more. The following day I was told that more than 1,500 had died this way,” wrote Bourgogne.

“Many were intoxicated, and fell asleep on the snow, to wake no more. The following day I was told that more than 1,500 had died this way,” wrote Bourgogne.

Those ready to leave, as depicted by Sergeant Dornheim from Lippe, were too numbed by the six months of misery to take pity on them. A colonel from Westphalia was preparing for his coffee, mixed with snow in a small pot on the fire.

“He was about to take this off and drink down the stimulating brew when a crowd of soldiers pushed so close to the fire that the poor colonel fell on his face and upset the coffee-pot.” It was no minuscule incident, for the routine would have been the only source of warmth.

“Oh, my God! Not that too!” he cried “in tones of extreme anguish,” but without resentment-invoking “feelings and sympathy” to Dornheim, and laughter to the others-“of the opinion that the colonel needed no coffee to drink, as they were not drinking any either.”

(More/Replies)

(More/Replies)

Roguet’s division of the Young Guard tried to catch some sleep before dawn. Bourgogne, who had looked everywhere for Faloppa in vain, stayed wide awake despite being next to “a well-heated stove.”

(Bourgogne)

(Bourgogne)

Captain Rudnicki of the 4th Infantry Regiment woke up at dawn “to see with astonishment that [he] was alone in the room.” The French soldiers who had shared the room with him were all gone. The owner of the house, a Pole, came running in, pleading:

“For the sake of Motherland, Sir, leave at once, for the Cossacks are already at the city walls…I have learned from your corporal that your wounded legs do not allow you to escape from the hands of the enemy, so I have decided to give you a little, quite strong pony…”

He tightly embraced “this noble patriot,” who also gave him “a bag of lentils and a sheepskin coat.” He belonged to Victor’s X Corps, the other half of the Grande Armée who had never seen Moscow. (Rudnicki)

New mournings accompanied the new daylight, as Labaume wrote:

“Poor Colonel Vidman’s death particularly affected us. He was one of the small number of the Italian Guard of Honor who had survived up to then.

“Poor Colonel Vidman’s death particularly affected us. He was one of the small number of the Italian Guard of Honor who had survived up to then.

Feeling unable to go a step farther, he fell while leaving Kowno to reach the bridge, and expired without having had the satisfaction of dying beyond the Russian frontier.” (Labaume)

General Lariboissière also fell gravely ill. In a few days, he would follow the two Dutch boys whom he had ousted from their shelter two days ago, found stiff-frozen last morning. (Zamoyski, Foord)

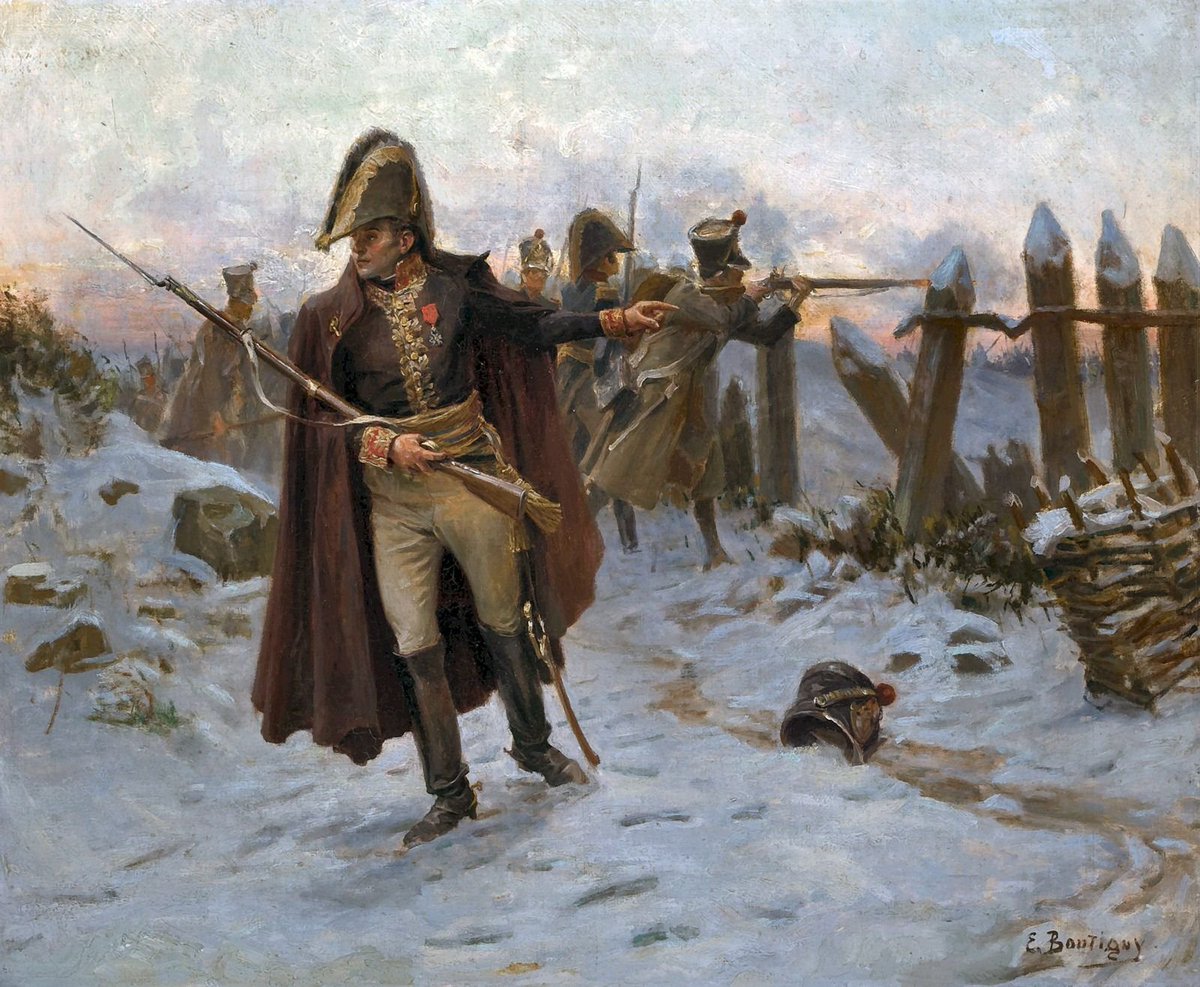

To wallow in sorrow was a luxury, for their second crossing was about to begin. For the next 48 hours, they would have Ney at their back. With 60 men to himself, 300 to Loison, 400 to Marchand, and few hundreds to Maison, the marshal entrenched himself in Kovno. (Segur)

One of those guns had already been dismounted at the enemy's first cannon shot. And as both Ney and Gérard later reported furiously, all the guns had been "spiked by the ineptitude of the officer commanding them." (Gérard, Austin)

It only seemed to Fezensac that the rearguard, scarcely a thousand men in total, was “now being told to remain in Kovno to try to defend it, or rather perish honorably in its ruins.” All that Ney demanded to Murat was support from Gérard’s division, which was granted.

(Thiers)

(Thiers)

Watching the main army huddled up on the bridgehead, Gérard thought "[e]veryone was abandoning us."

"But just then," as Fezensac wrote, "the Marshal appeared on the rampart. His absence had seemed to be the end of us. His presence was enough to set everything to rights."

"But just then," as Fezensac wrote, "the Marshal appeared on the rampart. His absence had seemed to be the end of us. His presence was enough to set everything to rights."

The main army thus deserted their last town in Russia. They began marching on the road on their left, leading to Tilsit and Gumbinnen. They were lucky that Wittgenstein had not begun his movement to the same direction, as ordered by Kutuzov. (Thiers, Foord, Wilson)

At last, the army of 20,000 saw their Styx again-“the same spot, whence five months previously their countless eagles had taken their victorious flight.”

They shed silent tears, exclaiming:

“This then was the bank which they had studded with their bayonets!”

(Segur)

They shed silent tears, exclaiming:

“This then was the bank which they had studded with their bayonets!”

(Segur)

As Marbot saw Kovno disappearing into the mist, he could not help reminiscing:

“Five months before we had entered the Empire of the Czar at the same spot. What a change had since then taken place in our fortunes, and what had been the loss of the French army!”

“Five months before we had entered the Empire of the Czar at the same spot. What a change had since then taken place in our fortunes, and what had been the loss of the French army!”

Labaume could not bring himself to believe that “out of 400,000 warriors who, at the opening of the campaign had crossed the Niemen near Kovno, scarcely 20,000 repassed the river, and of these at least 2/3 had never seen the Kremlin.

According to Segur’s dramatic rendering of the moment, the men lapsed into unbridled grief as they realized:

“The Neman is now only a long mass of flakes of ice, caught and chained to each other by the increasing severity of the winter. Instead of the three French bridges,

“The Neman is now only a long mass of flakes of ice, caught and chained to each other by the increasing severity of the winter. Instead of the three French bridges,

brought from a distance of 500 leagues, and thrown across it with such audacious promptitude, a Russian bridge is alone standing.”

Tottering on it were “only a thousand infantry and horsemen still under arms, 9 cannon, and 20,000 miserable wretches covered in rags.”

Tottering on it were “only a thousand infantry and horsemen still under arms, 9 cannon, and 20,000 miserable wretches covered in rags.”

The stragglers who had managed to follow became completely delirious. They “dressed in the middle of the street” and mechanically rushed ahead.

(Fezensac)

The river was “frozen so hard that it would have borne the weight of artillery,” had they any.

(Labaume)

(Fezensac)

The river was “frozen so hard that it would have borne the weight of artillery,” had they any.

(Labaume)

When Bourgogne woke up from a nap, the first thing he did was to search for Faloppa.

At last, someone found him in the same hut, doing “nothing but prowl about the stable on all fours, howling like a bar.” Bourgogne could never forget his jovial friend’s descent into madness.

At last, someone found him in the same hut, doing “nothing but prowl about the stable on all fours, howling like a bar.” Bourgogne could never forget his jovial friend’s descent into madness.

“I knew that he thought he was in his own country in the midst of the mountains, playing with the friends of his childhood; now and again he called for his mother."

Just as Bourgogne forced himself away, he heard Roguet "swearing and dealing blows to everyone indefinitely."

Just as Bourgogne forced himself away, he heard Roguet "swearing and dealing blows to everyone indefinitely."

"Certainly this distribution of blows came easier to him than the distribution of bread and wine which he had made in Spain," Bourgogne thought, as he joined a column of men hurrying to the bridgehead.

Colonel Bodelin harangued, "Come, my men! I will not tell you to be brave-

Colonel Bodelin harangued, "Come, my men! I will not tell you to be brave-

I know how much courage you have. During the three years I have been with you you have given proofs...But, remember, the more distress and danger, the more glory and honor, and the greater the reward for those who had the endurance to go through with it." (Bourgogne)

"Those who had survived the disasters in Russia resembled, more and more, a band of robbers than the remnants of a great army," wrote Major Vionnet, who had made it to Kovno at 10 a.m. on the 13th. He was disgusted by those stealing "pretty much...whatever they could find."

The recrossing was not as cathartic as it should have been; because the Neman had hardened into a sheet of ice, many did not realize that it was the same river they had set their foot on about half a year ago.

At the time, Napoleon's carriages were heading to Dresden. The Emperor kept "cherishing illusions...in no way put out with [Caulaincourt] for not sharing in them."

As he discussed several candidates for his son's tutor, he became increasingly mellow with nostalgia.

(More)

As he discussed several candidates for his son's tutor, he became increasingly mellow with nostalgia.

(More)

He dwelled on the nature of man, that its essence lies in nothing but self-interest. Enumerating several figures of prominence, he uttered:

"Even patriotism...is a word that conveys nothing to them if it is not consonant with their own interests..."

"Even patriotism...is a word that conveys nothing to them if it is not consonant with their own interests..."

He pondered on the inherently violent, paranoid nature of regime transition-the turmoil of which he had exploited to his glory. He admitted taking pity on King Louis XVI, for "it was fear rather than hatred or spite that inspired [the judges'] sentence."

By the same token, he became abhorrent to the idea of people idolizing him.

"I have no idols made of me, nor even any outdoor statues...I want no homage in the form of flattery, nor, as happened to Louis XV, a statue subjected to public ridicule."

"I have no idols made of me, nor even any outdoor statues...I want no homage in the form of flattery, nor, as happened to Louis XV, a statue subjected to public ridicule."

He did recollect "with pleasure...some of the incidents of his youthful days"-from his boyhood at the Brienne Academy to "various affairs of gallantry" to women. But he could never deny that Josephine was his foremost confidante.

"In short," added Caulaincourt in the footnote, "if this great and astonishing character had a flaw, it was through the conceit of past achievement."

If there was anyone willing to sacrifice himself to rekindle his past glory, it was Ney.

If there was anyone willing to sacrifice himself to rekindle his past glory, it was Ney.

It was about 2 p.m. when the Young Guard heard "The Cossacks! To arms!" (Bourgogne)

Wilson narrated the climactic moment:

"In the midst of this direful distress, Platov, with his Cossacks and guns, arrived...where the heavy guns by some mistake of orders had been spiked."

Wilson narrated the climactic moment:

"In the midst of this direful distress, Platov, with his Cossacks and guns, arrived...where the heavy guns by some mistake of orders had been spiked."

Platov, who had lost his only son in the campaign, was resolved to make Kovno their graveyard.

The fresh conscripts in Loison's 34th division, dressed in beautiful uniforms, flurried at the first sight of the Cossacks. (Austin, Wilson)

The fresh conscripts in Loison's 34th division, dressed in beautiful uniforms, flurried at the first sight of the Cossacks. (Austin, Wilson)

Thanks to them, Gérard took over some of their guns and made the 29th Regiment guard the frontyard.

General Marchand, with his 27th Regiment, "made a sally to dislodge the Cossacks from the height of Alexioten" adjacent to the Kovno garrison. (Gérard , Austin, Wilson)

General Marchand, with his 27th Regiment, "made a sally to dislodge the Cossacks from the height of Alexioten" adjacent to the Kovno garrison. (Gérard , Austin, Wilson)

Ney, alongside the intoxicated stragglers and their corpses, those fleeing away, and the kernel of men under Gérard and Marchand, "took up a musket" and "fought like a common soldier for the position whose preservation he considered so important." (Fezensac)

"This semblance of a resistance began to contain the enemy, and by redoubling my activity, by begging each and every man, man by man, to show some zeal, I managed to last out until night began to fall," wrote Gérard, seeing the enemy withdrawing around 9 p.m.

At 9:30 p.m., Ney's men "passed through Kovno amid the dead and the dying," the stragglers "who watched [them]...with indifference," and the locals who "looked at [them] insolently."

Seeing the rearguard finally evacuating Kovno, the Young Guard at Wirballen got on the move.

Seeing the rearguard finally evacuating Kovno, the Young Guard at Wirballen got on the move.

Bourgogne felt himself about to collapse, but Grangier, "already three-quarters up" the bridge, stopped and "made signs that he would be there" for him.

He reciprocated by clutching onto his last breath:

"I fell on my side, and rolled as far as the Neman, landing on the ice."

He reciprocated by clutching onto his last breath:

"I fell on my side, and rolled as far as the Neman, landing on the ice."

His face was bleeding, and shoulder aching from falling innumerable times. When he saw Eugene's men at a distance, he "picked myself up without a word, as if it was something perfectly natural," for he was "so inured to suffering that nothing surprised [him]." (Bourgogne)

- The End-

Hope everybody had a good day.

Hope everybody had a good day.

@threadreaderapp Unroll!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh