#OTD 15 December, 1812, Napoleon revisited Erfurt, where he conveyed his greetings to Goethe via the French ambassador to Saxony.

His army scattered along the road to Prussia, with some of them already full of excitement at leaving the battlefield altogether.

#Voicesfrom1812

His army scattered along the road to Prussia, with some of them already full of excitement at leaving the battlefield altogether.

#Voicesfrom1812

By the morning, Napoleon's carriages had nearly flown through Dresden, Leiptzig, Lützen, and Weimar. In the last city, Caulaincourt was supposed to meet Baron St. Aignan, the French Ambassador to the Saxon court and his own brother-in-law. (Caulaincourt)

Because the homely procession moved at such a blistering pace, with Napoleon having his coffee "without alighting from the carriage," the poor minister only caught up with them at Erfurt.

At last, all three could stop to enjoy an hour-long breakfast.

At last, all three could stop to enjoy an hour-long breakfast.

Napoleon received him affectionately and asked him to convey his greetings to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Four years ago, on 2 October, 1808, the Emperor had visited the same town and invited the literati to discuss "Werther, which he must have studied in detail." (Goethe)

Goethe had recorded Emperor's remark, uttered callously during his fleeting heyday; on the nature of "fatalistic plays," Napoleon questioned, "What point is there these days in talking about destiny?...Politics is today's destiny."

Thanks to St. Aignan, Napoleon and Caulaincourt were provided with "a landau...fitted up so that the Emperor could lie at full length in it." The Saxon gendarme who had accompanied them from Dresden were switched with the French one, heightening Napoleon's sense of homecoming.

The French ambassador did not forget to deliver messages of goodwill from "the Emperor of the Night," as dubbed by Karl August. (Heinrich Düntzer)

The news of Napoleon's return agitated him, for he, despite admiring the Emperor's genius, disdained the incursion of his empire.

The news of Napoleon's return agitated him, for he, despite admiring the Emperor's genius, disdained the incursion of his empire.

The incident at a posthouse, which the two entered in the pending nightfall, could have foreshadowed the incipient discontent of the German states.

The postmaster, courteous on the surface, kept his guests waiting for the new horses for two hours.

The postmaster, courteous on the surface, kept his guests waiting for the new horses for two hours.

When the man parroted nothing but Gleich! (immediately!), Caulaincourt began to suspect a ploy to ambush them in the dark.

He went down to the stables himself and, suppressing his anger, "tapped on the door softly, saying...Mach auf."

He went down to the stables himself and, suppressing his anger, "tapped on the door softly, saying...Mach auf."

Mistaking the polyglot's voice for one of his colleagues', a postillon "opened the door immediately." When he unwittingly revealed to the guest "ten excellent horses" inside the barn, Caulaincourt ran to the postmaster who still "forbade his horses to be used."

"Upon this a great turmoil ensued," wrote Caulaincourt. He admitted exploding into a rare, unbridled anger:

"I grabbed him by the collar and forced him into a corner of the stable, ordering him to have the horses to put to instantly...He hesitated...I drew my sword..."

"I grabbed him by the collar and forced him into a corner of the stable, ordering him to have the horses to put to instantly...He hesitated...I drew my sword..."

At last, the postmaster let go of the horses-"[t]hanks to the sword point, which made him realize that I was a man of my word..." as Caulaincourt added.

Just on the day Napoleon felt France getting nearer to him, this disturbance caused both of them to be "alert all night."

Just on the day Napoleon felt France getting nearer to him, this disturbance caused both of them to be "alert all night."

At Wilkowysk, Murat's new headquarter, Berthier was writing up a grim report intended for the former commander-in-chief:

"There were not 300 great men of the Old Guard [on parade]; of the Young Guard fewer still, most of them unservicable."

(Berthier, 15 Dec 1812, Austin)

"There were not 300 great men of the Old Guard [on parade]; of the Young Guard fewer still, most of them unservicable."

(Berthier, 15 Dec 1812, Austin)

Regardless of Napoleon's catastrophic failure, many of the survivors were only content at having outlived the hellish campaign.

After six months of everyday farewell to their beloved friends, reunions-of the most unexpected kinds-were waiting for them in friendly countries.

After six months of everyday farewell to their beloved friends, reunions-of the most unexpected kinds-were waiting for them in friendly countries.

Bourgogne, who had lain beside a dying friend for the whole night, walked tirelessly, to fulfill his wishes:

"Dear friend, I am utterly unable to leave here-even to take a step-so you must do me a great service. I count on you, if you have the happiness to see France again..."

"Dear friend, I am utterly unable to leave here-even to take a step-so you must do me a great service. I count on you, if you have the happiness to see France again..."

For the last time the sergeant embraced Poton, his comrade on his frozen deathbed, and went to "religiously fulfill [his] mission."

The papers "contained his will, and the affecting farewell he had written during his fever," which Bourgogne made a spare copy of:

The papers "contained his will, and the affecting farewell he had written during his fever," which Bourgogne made a spare copy of:

Each word, Poton's last reserves of strength before death, would haunt Bourgogne for several years.

"For several years I gave up writing my Journal of the Russian Campaign...A singular Mania had come upon me; I doubted whether all that I had seen and endured,

"For several years I gave up writing my Journal of the Russian Campaign...A singular Mania had come upon me; I doubted whether all that I had seen and endured,

with so much courage and patience in this terrible campaign was not the effect of my resignation."

But he felt himself obliged to live on behalf of his unfortunate friend. At 7 a.m., he found solace among his fellow survivors, Grangier included-sharing "indelible impressions."

But he felt himself obliged to live on behalf of his unfortunate friend. At 7 a.m., he found solace among his fellow survivors, Grangier included-sharing "indelible impressions."

With Grangier by his side, Bourgogne began marching on the road to nowhere; stopping and faltering every hour to grab his stomach aching from colic.

To his relief, the "sky was clear, and the cold bearable" thorughout the day.

To his relief, the "sky was clear, and the cold bearable" thorughout the day.

At 3 p.m., when Bourgogne decided to call it quits for the day, the two wanderers discovered "several soldiers of the different army corps" gathered around a house and a large bivouac fire.

But what surprised the wanderer more than the shelter was a woman in the crowd.

But what surprised the wanderer more than the shelter was a woman in the crowd.

It was unmistakeably Marie, a pretty cantiniere Bourgogne had met in Krasny on 22 November. On that day, Bourgogne took a liking to her and named her his wife-his only source of comfort in the middle of the defiles strewn with frozen corpses.

On the next morning, Bourgogne woke up to find her gone, and sulked for several days-making himself mistaken for a madman by the officers.

"I am not mistaken...Mon pays, is it really you?" He asked, pitying how "poor Marie's freshness had disappeared."

"I am not mistaken...Mon pays, is it really you?" He asked, pitying how "poor Marie's freshness had disappeared."

It turned out that she had had a second husband in the army,-"a fencing-master, and rather a bad lot," as Bourgogne wrote with a tinge of envy-.

The others also gathered to take a glance at Marie, emaciated but still beautiful-looking, especially amidst the throng of soldiers.

The others also gathered to take a glance at Marie, emaciated but still beautiful-looking, especially amidst the throng of soldiers.

One of them, as if oblivious to his misery, swore:

"Marie...has had a second husband in a year, and if she likes I will marry her for a third!"

Just a day after the end of the horrendous campaign, he was already in the mood for love.

"Marie...has had a second husband in a year, and if she likes I will marry her for a third!"

Just a day after the end of the horrendous campaign, he was already in the mood for love.

Far away, on the "German side of the [Neman]," Intendent Dumas was warming himself at a French physician's house until a man with a blackened face entered.

"At last I am here," said the intruder, throwing himself into a chair, making himself at home in the blink of an eye.

"At last I am here," said the intruder, throwing himself into a chair, making himself at home in the blink of an eye.

“What, General Dumas, do you not know me?” asked the stranger. Looking at the puzzled face, he said:

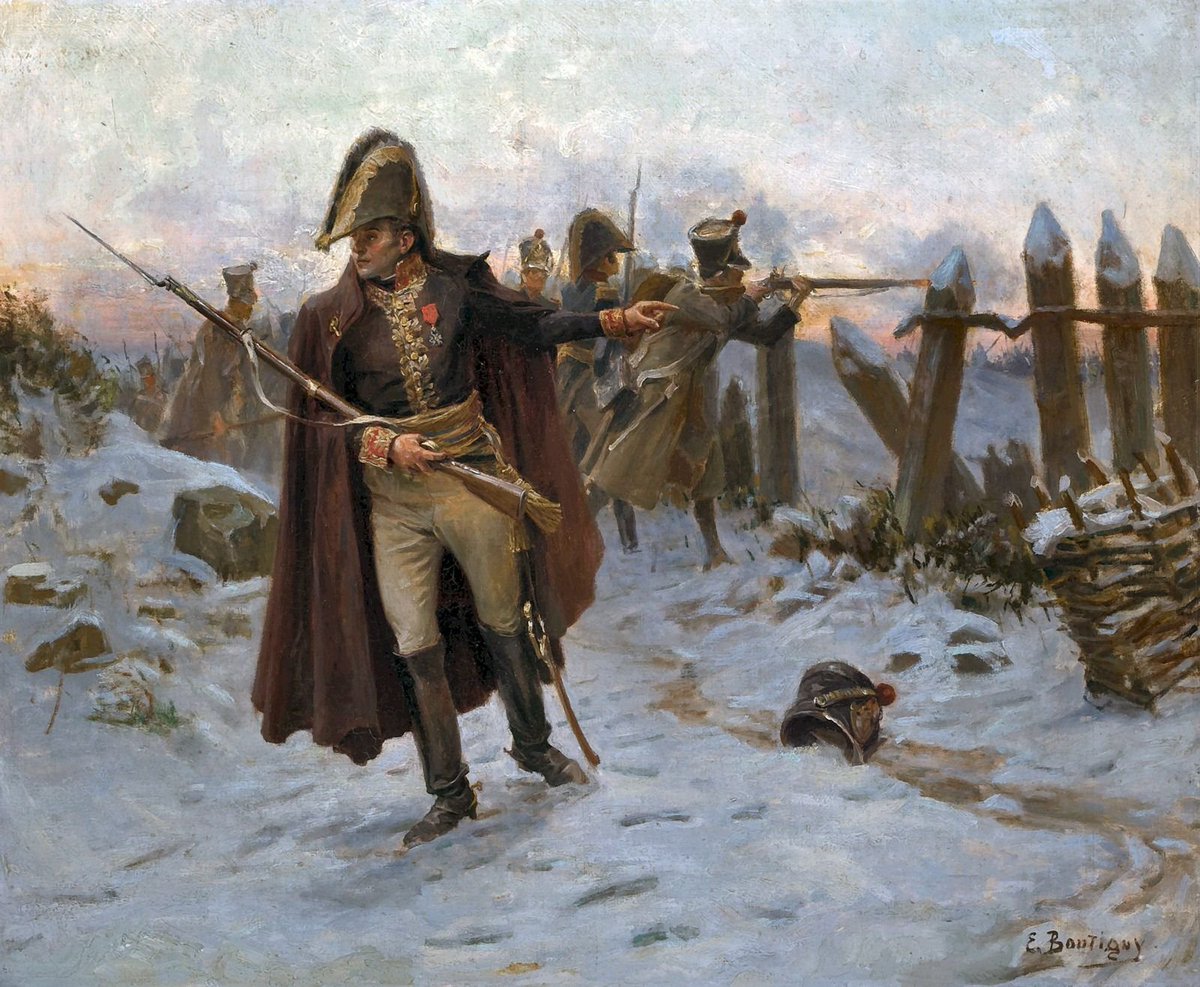

“I am the rearguard of the Grand Armée, Marshal Ney. I have fired the last musket shot on the bridge of Kovno, I have thrown into the Niemen the last of our arms…”

“I am the rearguard of the Grand Armée, Marshal Ney. I have fired the last musket shot on the bridge of Kovno, I have thrown into the Niemen the last of our arms…”

-End-

@threadreaderapp Unroll.

I am so tired..

I am so tired..

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh