#OTD 16 December, 1812, the carriages of Napoleon and Caulaincourt crossed the Rhine and finally entered the French territory.

The retreating army, in the meantime, trickled into the Prussian soil, where they witnessed a nationwide resentment against the French.

#Voicesfrom1812

The retreating army, in the meantime, trickled into the Prussian soil, where they witnessed a nationwide resentment against the French.

#Voicesfrom1812

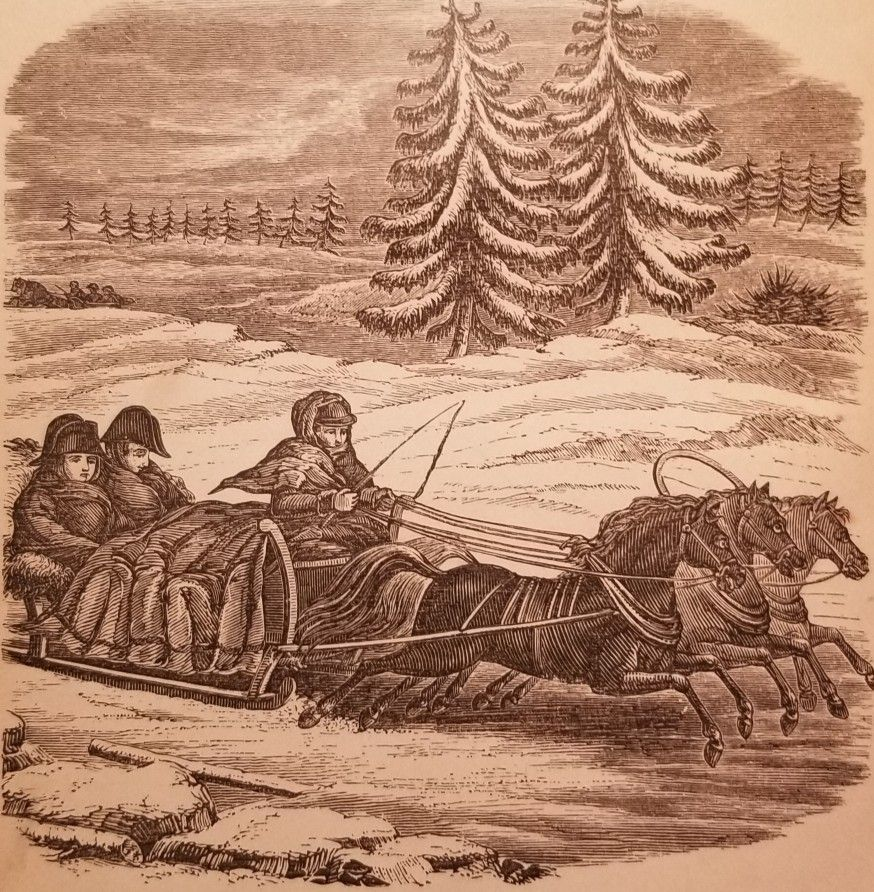

Following last night's scuffle at a postal station near Vigenov, the two travellers became "so glad to see daybreak" in safety.

"It was bitter cold. We travelled rapidly, despite the bad Westphalian roads," wrote Caulaincourt as the carriages set off again.

"It was bitter cold. We travelled rapidly, despite the bad Westphalian roads," wrote Caulaincourt as the carriages set off again.

They made a brief stop at Hanau, where they breakfasted and met Franz von Albini ['d'Albini' as Caulaincourt referred to him], the Minister of the Grand Duchy of Frankfurt.

He was "not a little surprised to see His Majesty, especially with such a modest suite."

He was "not a little surprised to see His Majesty, especially with such a modest suite."

A league before the Rhine, they caught up with Anatole Montesquiou, on his way back from Paris after delivering Napoleon's 29th Bulletin written in Molodechno, dated 3 December. They were about to part ways at the river, but the envoy found his passage clogged with floating ice.

Montesquiou was invited to join their journey home, while their carriages were carried across the Rhine by a boat. The company of three was now within the French borders. Caulaincourt could "never remember seeing the Emperor so light-hearted."

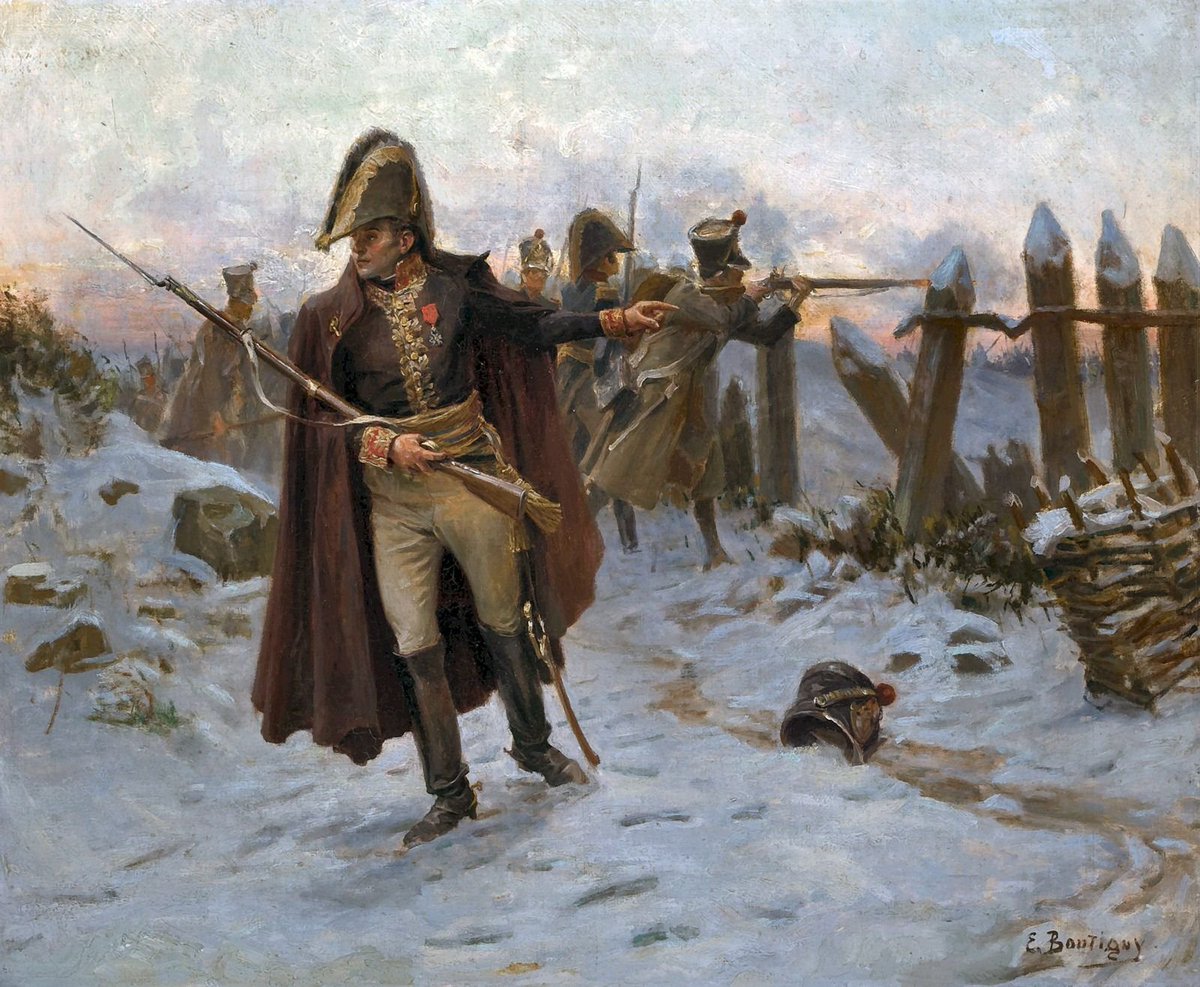

Just as the carriages, no longer travelling clandestinely, left the Confederation of the Rhine, the fugitives began to set their foot in Prussia. According to Vionnet, it "was still very cold on that day, in particular the wind was so cold that it took one's breath away."

Vionnet and various clutters of the Grande Armée had been staying at Wirballen, a town in East Prussia, since the previous day. According to Marbot, "the army had no longer a commander , and the remains of each regiment marched independently through Prussia."

Attesting to the state of disorder was Berthier's letter to Napoleon, written in cipher:

"The King of Naples is the the first of men on the battlefield...the King of Naples is the man least capable of commanding in chief. He should be replaced at once."

(Austin)

"The King of Naples is the the first of men on the battlefield...the King of Naples is the man least capable of commanding in chief. He should be replaced at once."

(Austin)

Others, like Bourgogne, were still three to four leagues before joining the headquarter in Wirballen.

Before daybreak, the sergeant bade farewell to Marie for the last time and set out to continue his pilgrimage. The men were now "in Pomeranian Prussia." (Bourgogne)

Before daybreak, the sergeant bade farewell to Marie for the last time and set out to continue his pilgrimage. The men were now "in Pomeranian Prussia." (Bourgogne)

The German soldiers' happiness could be surpassed by none of the others. Major von Lossberg, who had arrived on the 15th, rejoiced "to find oneself once more in a warm room among friendly people in a house (yes, in a town) where everyone speaks German."

In a letter to his wife, he could not emphasize enough that he was here "after a march, or rather a wander, of forty-nine days in such a country at this season and in the climate and circumstances that prevailed."

Lossberg could only thank Providence for everything.

Lossberg could only thank Providence for everything.

His relief and excitement were palpable in his words:

"I am in perfect health and have definite prospects of being with you soon! Yes, that is truth!"

Even the locals received him with "the most sincere sympathy." (Lossberg)

"I am in perfect health and have definite prospects of being with you soon! Yes, that is truth!"

Even the locals received him with "the most sincere sympathy." (Lossberg)

Jakob Walter, another German conscript from Stuttgart, was also treated favorably by a local nobleman. Being penniless, he was knocking on the door of a manorhouse to beg for bread. A servant came out and asked his nationality-only a budding concept at the time.

Walter "told him everything, that I was a Catholic and that the late sovereign of my country had been a prince of the King of Poland, etc. This pleased the man immensely, because when the Polish people knew that one was a Catholic they esteemed him much above the others."

By a stroke of luck, he "obtained not only bread but also butter and brandy." They must have made a feast to the footsoldier who had survived on horses' blood and a jar of honey taken from Moscow.

The French, however, would not be spoiled with the same favor.

(Walter)

The French, however, would not be spoiled with the same favor.

(Walter)

Bourgogne, for the first time since his departure from Russia, had changed his clothes, describing the process step-by-step:

"I took off my jacket and overcoat, and my waistcoat with the quilted yellow silk sleeves that I had made out of a Russian lady's skirt at Moscow.

"I took off my jacket and overcoat, and my waistcoat with the quilted yellow silk sleeves that I had made out of a Russian lady's skirt at Moscow.

I untied the shawl which was wrapped round my body, and my trousers fell about my heels. As for my shirt, I had not the travel of taking it off, for it had neither back nor front; I pulled off in shreds. And there I was, naked, except for a pair of wretched boots,

in the midst of a wild forest, at four o'clock in the afternoon [of the 15th], with eighteen to twenty degrees of cold, for the north wind had begun to blow hard again.

On looking at my emaciated body, dirty, and consumed with vermins, I could not restrain my tears."

On looking at my emaciated body, dirty, and consumed with vermins, I could not restrain my tears."

Having marched without a night's sleep, Bourgogne and his comrades came halfway to Wirballen before daybreak, when they ran across a dozen of men dressed like Cossacks.

Laughing at the suspicious gaze of his compatriots, one of them provided the story behind their appearances.

Laughing at the suspicious gaze of his compatriots, one of them provided the story behind their appearances.

After leaving Kovno, the trooper was approached by a band of Cossacks "laden with gold and silver." Without even bothering to restrain their prey, they ordered him to march in front of them.

"I was a prisoner, though I could not realize it," he said.

"I was a prisoner, though I could not realize it," he said.

Not surprisingly, he soon made his escape, only to be captured by a bigger party of Cossacks and their captives from the Imperial Guard.

At night, the French prisoners were lumped together into a barn, where the trooper miraculously found his brother lost at the Berezina.

At night, the French prisoners were lumped together into a barn, where the trooper miraculously found his brother lost at the Berezina.

Seeing the Cossacks out of sight, all of them began their escapade. The clever trooper "handed [his] brother a Cossack's lance, and covered him with the great camel's hair-cape..found on the horse" he had taken from the barn.

Dressed as a lone Cossack and his French captive, the brothers walked all the way to a Pomeranian village.

The locals kept approaching them, saying to his brother in German, "Good evening, friend Cossacks!", while cursing his captive walking on foot.

The locals kept approaching them, saying to his brother in German, "Good evening, friend Cossacks!", while cursing his captive walking on foot.

"We were led before the burgomaster, who made my brother exceedingly welcome, telling him that he should be quartered with him, and his horse taken care of; but as for the Frenchman, he would have him sent to the prison," he told Bourgogne.

The "brother Cossack" had to make up a story, that "this Frenchman" was a "Surgeon-Major" who will dress his wounded leg.

This improvised response delayed their leave, for three midwives resembling "three Fates" pleaded the French surgeon to give them a hand.

(More)

This improvised response delayed their leave, for three midwives resembling "three Fates" pleaded the French surgeon to give them a hand.

(More)

"Imagine my embarrassment!" the trooper said. Fortunately, his task was not a difficult one; he just had to find out whether the newborn was alive.

After he laid his frozen hand on the sickly woman, "in less than five minutes all was over-a Prussian subject was born."

After he laid his frozen hand on the sickly woman, "in less than five minutes all was over-a Prussian subject was born."

The tale of his bizarre adventure, although hilarious, was indicative of widespread anti-French sentiments in the German states, as well as the lingering presence of the Cossacks nearby.

In fear of the latter, Bourgogne's party hurried for the headquarter and arrived at 4 a.m.

In fear of the latter, Bourgogne's party hurried for the headquarter and arrived at 4 a.m.

"It was December 16th, the fifty-ninth day's march since leaving Moscow. The wind was high and the cold terrible," he recorded the opening of the day, when he felt nothing but a desire to sleep. His eyes became wide open as he saw again Picart, his friend who had been missing.

The newly arrived were told that Murat would be holding a review at 3 p.m., prompting Bourgogne to have his "first shave since leaving Moscow."

This review, according to Vionnet, was conducted, but Bourgogne wrote that "Murat did not come."

This review, according to Vionnet, was conducted, but Bourgogne wrote that "Murat did not come."

Having nothing else to do, Picart offered Bourgogne "a good pull of white wine-Rhine wine."

Just as he had done in Vilna-passing himself as the son of a Jewish shopkeeper to get food from the locals-he got the wine by "humming the Rabbi's chant" at a synagogue.

Just as he had done in Vilna-passing himself as the son of a Jewish shopkeeper to get food from the locals-he got the wine by "humming the Rabbi's chant" at a synagogue.

The survivors, indeed, proved themselves to be the shrewdest and the most strong-willed of the army.

In the meantime, the thought of reaching Paris in 48 days stirred Napoleon's excitement to no end-so much that he generously joked about the political instability in Paris.

In the meantime, the thought of reaching Paris in 48 days stirred Napoleon's excitement to no end-so much that he generously joked about the political instability in Paris.

"In forty-four hours, Sire." Caulaincourt did his Emperor a favor by subtracting four hours from the forecast.

"I say in thirty-six," Napoleon immediately countered him and "began to tease [his] ear and joke about the eight hours that he was obliged to add."

"I say in thirty-six," Napoleon immediately countered him and "began to tease [his] ear and joke about the eight hours that he was obliged to add."

Remembering his Emperor alight with joy, Caulaincourt reminisced:

"Each state, each quarter of a stage, each quarter of an hour, each minute, were reckoned up...He seemed so confident and happy that for me, one of the pleasant moments of our journey."

"Each state, each quarter of a stage, each quarter of an hour, each minute, were reckoned up...He seemed so confident and happy that for me, one of the pleasant moments of our journey."

-The End-

@threadreaderapp Unroll.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh