#OTD 17 December, 1812, when Murat's army began to find quarters in Gumbinnen, the 29th Bulletin of the Russian Campaign was published in Le Moniteur. This virtual admission of defeat, previously unseen in Napoleon's bulletins, threw Paris into consternation.

#Voicesfrom1812

#Voicesfrom1812

The bulletin from Molodechno, dated 3 December, began by describing a sudden, ominous drop in temperature on 7 November, two days before Napoleon reentered Smolensk:

"To the 6th of November the weather was fine, and the movement of the army executed with the greatest success."

"To the 6th of November the weather was fine, and the movement of the army executed with the greatest success."

The cold only worsened with increasing rapidity on the eve of the Battle of Krasny, the "14th, 15th, and 16th," when "the thermometer was sixteen and eighteen degrees below the freezing point."

Thenceforth was the beginning of the end.

Thenceforth was the beginning of the end.

On the "roads covered with ice," more than 30,000 horses, especially the German and French breeds, "perished every night."

The cold and the resulting losses of the means of transportation made "[t]his army, so fine on the 6th, was very different on the 14th."

The cold and the resulting losses of the means of transportation made "[t]his army, so fine on the 6th, was very different on the 14th."

Napoleon then detailed his army's descent to destitution from Smolensk to the Berezina, with a surprising degree of transparency:

"Without cavalry, we could not reconnoitre a quarter of a league's distance; without artillery, we could not risk a battle, and firmly await it...

"Without cavalry, we could not reconnoitre a quarter of a league's distance; without artillery, we could not risk a battle, and firmly await it...

This difficulty, joined to a cold which suddenly came on, rendered our situation miserable. Those men, whom nature had not sufficiently steeled to be above all the chances of fate and fortune, appeared shook , lost their gaiety-

their good humour, and dreamed but of misfortunes and catastrophes; those whom she has created superior to everything, preserved their gaiety, and their ordinary manners, and saw fresh glory in the different difficulties to be surmounted.

The enemy, who saw upon the roads traces of that frightful calamity which had overtaken the French army, endeavoured to take advantage of it. He surrounded all the columns with his Cossacks, who carried off, like the Arabs of the desert, the trains and carriages..."

Of course, he did not forget to blame Partouneaux's "cruel mistake" which "must have caused us a loss of 2,000 infantry, 300 cavalry." He also claimed that "[t]he artillery has already repaired its losses" at Molodechno, when each corps had only a dozen of guns.

The Bulletin profusely commended "what officers and soldiers have chiefly distinguished themselves," "the fine spirit shewn by his guards" and especially the sacrifices made by the 'Sacred Squadron'-the existence of which might not have been known without this acknowledgement:

"Our cavalry was dismounted to such a degree, tbat it was necessary to collect the officers who had still a horse remaining, in order to form four companies of 150 men each. The Generals there performed the functions of captains, and the colonels of subalterns.

This Sacred Squadron, commanded by General Grouchy, and under the orders of the King of Naples, did not lose sight of the Emperor in all these movements."

The report, then, ended with the infamous remark:

"The health of His Majesty was never better."

The report, then, ended with the infamous remark:

"The health of His Majesty was never better."

As soon as the copies of Le Moniteur were distributed in the morning, the whole of Paris became seized with consternation. The bulletin came as nothing but a final, unprecedentedly blatant admission of defeat by the Emperor himself.

Napoleon's words, although glossed over comparaed to the individual accounts of their abject situation, were not what Bourrienne called "one of those lying bulletins."

The unusual bulletin, then, incited mixed reactions from the Parisian public.

The unusual bulletin, then, incited mixed reactions from the Parisian public.

Baron Pasquier, Minister of Police, described the atmosphere of panic:

"Events of the most serious and tragical import quickly occurred to give a new turn to opinion. Week after week the intelligence from the theater of war became more alarming, and of the worst omen...

"Events of the most serious and tragical import quickly occurred to give a new turn to opinion. Week after week the intelligence from the theater of war became more alarming, and of the worst omen...

and at last the famous 29th Bulletin informed France of the disaster that had befallen her arms." (Pasquier)

His predecessor, Fouché, saw how the publication "carried mourning into so many families" waiting for the arrival of their husbands and sons from Russia.

(Fouché)

His predecessor, Fouché, saw how the publication "carried mourning into so many families" waiting for the arrival of their husbands and sons from Russia.

(Fouché)

He deplored the ill-fated campaign as "a new snare, held out to the devotedness and credulity of a generous nation; who, struck with consternation , thought that their chief, chastened by misfortune, was ready to seize the first favorable opportunity of bringing back peace."

Fouché criticized Napoleon for falsifying the unnecessary war as a peacemaking enterprise. This, in his opinion, had baited the whole nation to make "willingly...the greatest sacrifices to sustain a man whose only success had been that of spurning the ashes of Moscow,

of carrying desolation into a vast extent of country which he had left covered with the corpses of a hundred and fifty thousand of his own subjects, and those of his allies, after abandoning a still greater number of prisoners, and the whole of his artillery and magazines."

In this context, even Napoleon's scheduled return to the throne seemed to show him "far less concerned on account of the loss of his army, than about the conspiracy which had revealed so fatal a secret as the fragility of the foundation of his empire." (Fouché)

Thiers, in his annals of the Napoleonic era, pointed out that that Napoleon, for "the first time in the course of the retreat...acknowledged that portion of the disasters," but was still reticent about admitting his own share of responsibility in the debacle.

Instead, he cited "the inclemency of the weather" as the foremost cause of his failure, disregarding the losses incurred during the summer; not to mention "relieving the account of his reverses by a description of the glorious and mortal passage of the Beresina."

(Thiers)

(Thiers)

To the common people, the most disconcerting part of the bulletin was the callous words that Napoleon's health has never been better.

Chateaubriand, a long critic of the administration, summed up their outrage:

"Families, dry your tears. Napoleon has never been better."

Chateaubriand, a long critic of the administration, summed up their outrage:

"Families, dry your tears. Napoleon has never been better."

Few others, however, appreciated the Emperor's attempt to convey as much truth as possible, when every correspondence could undermine his international reputation.

Baron Fain argues that "the Emperor wished to show France the misfortunes of the retreat."

Baron Fain argues that "the Emperor wished to show France the misfortunes of the retreat."

To strengthen his claim, he cited in the footnote a statement by Germaine de Staël, a political exile living in Russia. She emphasized that Napoleon, being a man "who loves producing strong emotions so much," was "exaggerating rather than concealing" his setbacks. (Fain)

(More)

(More)

While Paris was becoming enveloped in grief and confusion, Murat entered Gumbinnen, where he became "exceedingly surprised to find Ney already there," which meant that his army had been marching without a rearguard since leaving Kovno. (Segur)

As described in Bourgogne's memoir, the army behind did feel the effect of Ney's absence. Detachments of the Young Guard, including himself, had been harrassed multiple times by the Cossacks on the previous day, and became almost kidnapped by the Jewish drivers on this day.

Being too exhausted to resume marching at 5 a.m., the party of five had paid them a hefty sum for a ride.

Then, the sledge-drivers suddenly swerved to the direction opposite to Gumbinnen, as witnessed by Bourgogne:

Then, the sledge-drivers suddenly swerved to the direction opposite to Gumbinnen, as witnessed by Bourgogne:

"When we went near the town, the Jew wanted to go there under pretext of fetching something from his house; no doubt it was to give us up to the Cossacks, who were now filling the town. We gave him a taste of sword-point on his back, and threatened to kill him..." (Bourgogne)

Fortunately, they reached Gumbinnen "none too soon," where they all "received a billet, and had a very warm room and some straw."

According to Eugenie Oudinot, who had stayed there during the 12nd and 13rd, the town had "some sort of French organization" and "a good lodging."

According to Eugenie Oudinot, who had stayed there during the 12nd and 13rd, the town had "some sort of French organization" and "a good lodging."

She made a detailed observation of those who had crept into the town earlier:

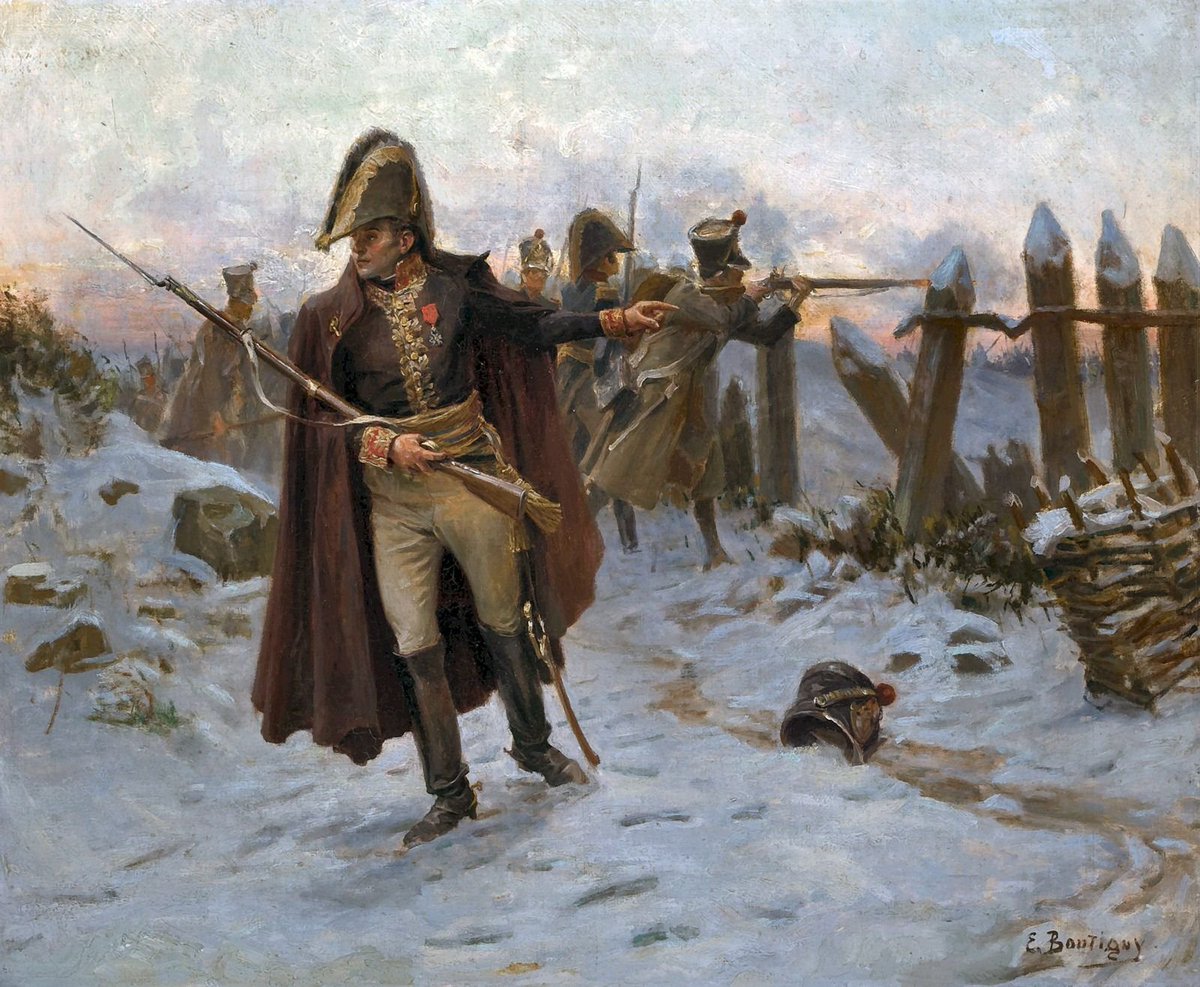

"Some were covered with furs, and looked like bears; others, who had lost all they had and were unable to buy anything in its stead, were clad in their full uniforms," most notably General Chasseloup.

"Some were covered with furs, and looked like bears; others, who had lost all they had and were unable to buy anything in its stead, were clad in their full uniforms," most notably General Chasseloup.

According to Marbot, Murat became "reproached for having taken the road to old Prussia," exposing the weakened troops to a hostile country.

As valid as the criticism was, those in Gumbinnen encountered remarkably little hostility compared to their earlier journey. (Segur)

As valid as the criticism was, those in Gumbinnen encountered remarkably little hostility compared to their earlier journey. (Segur)

Moreover, as Larrey mentioned, there was an abundance of "beds and also healthy food" for all, "both of which luxuries, for so they appeared, had been almost unenjoyed...since he quitted Moscow."

But what Berthezene called "a new scourge" was hovering over the camp.

But what Berthezene called "a new scourge" was hovering over the camp.

This consisted of neither the Cossacks nor hunger, but a fatal relaxation of the body and mind. Under the newfound warmth, the famished soldiers successively fell to stupor. They still had to be reminded of another 400 leagues between Königsberg and Paris. (Berthezene, Zamoyski)

As Murat settled into Gumbinnen, Napoleon travelled from Verdun to Mayence.

"After leaving the Dresden the Emperor spoke of nothing but Paris, of the Empress' surprise at seeing him, of how everyone would be astonished," wrote Caulaincourt.

"After leaving the Dresden the Emperor spoke of nothing but Paris, of the Empress' surprise at seeing him, of how everyone would be astonished," wrote Caulaincourt.

No longer travelling incognito in his own soil, Napoleon let the postillons announce his arrival at Mayence. But, as Caulaincourt recounted, "the postmasters would only believe it when they saw him for themselves."

(Caulaincourt)

(Caulaincourt)

Anticipating arrival within the next 24 hours, the Emperor "was much concerned with the effect his bulletin would have caused, and was surprised at getting no news of it." He seemed to be in the expectation that the publication would yield an effect opposite to the reality.

-The End-

@threadreaderapp Unroll.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh