#OTD 18 December, 1812, amidst the noises surrounding the 29th Bulletin, Napoleon returned to Paris after a fortnight's journey from Smorghoni.

On the samae day, Marshal Macdonald received a belated order to withdraw beyond the Neman.

#Voicesfrom1812

On the samae day, Marshal Macdonald received a belated order to withdraw beyond the Neman.

#Voicesfrom1812

It was well after the dark when a modest-looking coach, stained with frozen mud, appeared in Paris. Had it shown up during the day, it would have spawned much hubbub, for it rolled right into the Arc de Triomphe-an imperial prerogative.

(Caulaincourt)

(Caulaincourt)

One of the sentinels, withered by fourteen sleepless days on "Que Vive?", kept dozing off and shaking in the saddle. Inside the carriage, a man in a knee-length overcoat came out to usher the poor man to the front, telling him that they were now in front of the Tuileries.

The time was just a quarter before midnight after the suspicious carriages had slided past the Arc and the main gateway to the Tuileries, uninterrupted. The palace guards automatically took the passengers to be couriers fortunate enough to return from Russia alive. (Fain, Caul.)

"That's a good sign," said Napoleon, turning to Caulaincourt, who had his bearskin unbuttoned to expose the braid of his dress uniform.

No one had been informed of his arrival on the day, and Marie-Louise, most dearly missed by Napoleon, just went to her bedchamber. (Caul.)

No one had been informed of his arrival on the day, and Marie-Louise, most dearly missed by Napoleon, just went to her bedchamber. (Caul.)

After looking around, Caulaincourt knocked a door to the "open gallery that overlooks the Garden," and a porter came out holding a lamp.

"Our faces looked so strange to him that he called his wife," who "stuck the lamp right into my face," he recounted.

"Our faces looked so strange to him that he called his wife," who "stuck the lamp right into my face," he recounted.

Recognizing the Grand Equerry, the porter's wife dashed toward the Empress' chamber, exclaiming "It's the Emperor!"

But when the two ladies-in-waiting came down to make sense of the noise, they denied entry to the husband and his wingman, who described the moment:

But when the two ladies-in-waiting came down to make sense of the noise, they denied entry to the husband and his wingman, who described the moment:

"My two-weeks' beard, the state of my clothes, my fur-lined boots,-all this, I imagine, struck them unfavorably...for I had to repeat the good news of the Emperor's arrival over and over before I could stop their fleeing from the ghost they thought they saw."

(Ibid)

(Ibid)

Madame Durand, one of the ladies-in-waiting, illustrated the heartbreaking reunion of the imperial couple:

"Marie-Louise, who had been sad and unwell for some time, had just gone to bed. The chambermaid, who slept in the room next to hers, was preparing to do the same,

"Marie-Louise, who had been sad and unwell for some time, had just gone to bed. The chambermaid, who slept in the room next to hers, was preparing to do the same,

by closing all the doors, when she heard several voices from the drawing-room before her quarter.

Just as the door opened, she saw two men, covered with heavily lined coats, entering. She rushed to the door leading to the Empress' chamber to bar their entry,

Just as the door opened, she saw two men, covered with heavily lined coats, entering. She rushed to the door leading to the Empress' chamber to bar their entry,

when, one of the two having drawn his cloak aside, she recognized the Emperor. A cry she uttered informed the Empress that something extraordinary was happening in the adjoining room, and she was about to jump out of bed, when her husband took her in his arms."

(Durand, Fain)

(Durand, Fain)

"Good night, Caulaincourt. You need some rest, too," said Napoleon, craving respite after two weeks of nonstop journey. He instructed Caulaincourt, who "should have had trouble again being admitted" had he not come by the post-chaise, to go see Archchancellor Cambacérès. (Caul.)

He got off from his post-chaise-the only indicator of his rank-, and entered the court in great embarrassment:

"Everyone looked at me without saying a word. None knew what to make either of my arrival or of this figure that seemed not to fit the name which had been announced.

"Everyone looked at me without saying a word. None knew what to make either of my arrival or of this figure that seemed not to fit the name which had been announced.

After the first impression produced by my attire and my beard, the same thought came to them all:

'Where is the Emperor? What's the news? Can

something have happend to him?'"

The "terrible bulletin" published on the previous day had been shocking enough to them.

(Ibid)

'Where is the Emperor? What's the news? Can

something have happend to him?'"

The "terrible bulletin" published on the previous day had been shocking enough to them.

(Ibid)

As Caulaincourt waited for Cambacérès, all the notables went about whispering-without the slightest effort to silence themselves-that the Grand Equerry had returnd without Emperor.

"That dumb show cannot be described," the subject of their gossip bitterly remarked.

"That dumb show cannot be described," the subject of their gossip bitterly remarked.

But as soon as Caulaincourt informed Pierre Amédée Jaubert, and shortly thereafter the Archchancellor, that the Emperor was in Paris, "all their faces brightened up."

Cambacérès arranged for the cannons to celebrate his return at dawn, followed by a levee at 11 a.m.

Cambacérès arranged for the cannons to celebrate his return at dawn, followed by a levee at 11 a.m.

As Fain wrote, "[t]he news of his return...awakened his ministers," who had found his absence disconcerting.

As for Caulaincourt, he could only take a break after ordering pages to send the same notice to Madame Mère and each of Napoleon's sisters, at 8 a.m. (Caul.)

As for Caulaincourt, he could only take a break after ordering pages to send the same notice to Madame Mère and each of Napoleon's sisters, at 8 a.m. (Caul.)

It would not be so long before Napoleon forces himself out of the bed just after few hours of sleep. (Fain)

Talleyrand, in his memoir, cynically commented that Napoleon "still cherished chimerical hopes, and was meditating without doubt, more gigantic projects." (Talleyrand)

Talleyrand, in his memoir, cynically commented that Napoleon "still cherished chimerical hopes, and was meditating without doubt, more gigantic projects." (Talleyrand)

On this day, the details of Napoleon's homecoming was publicized as below:

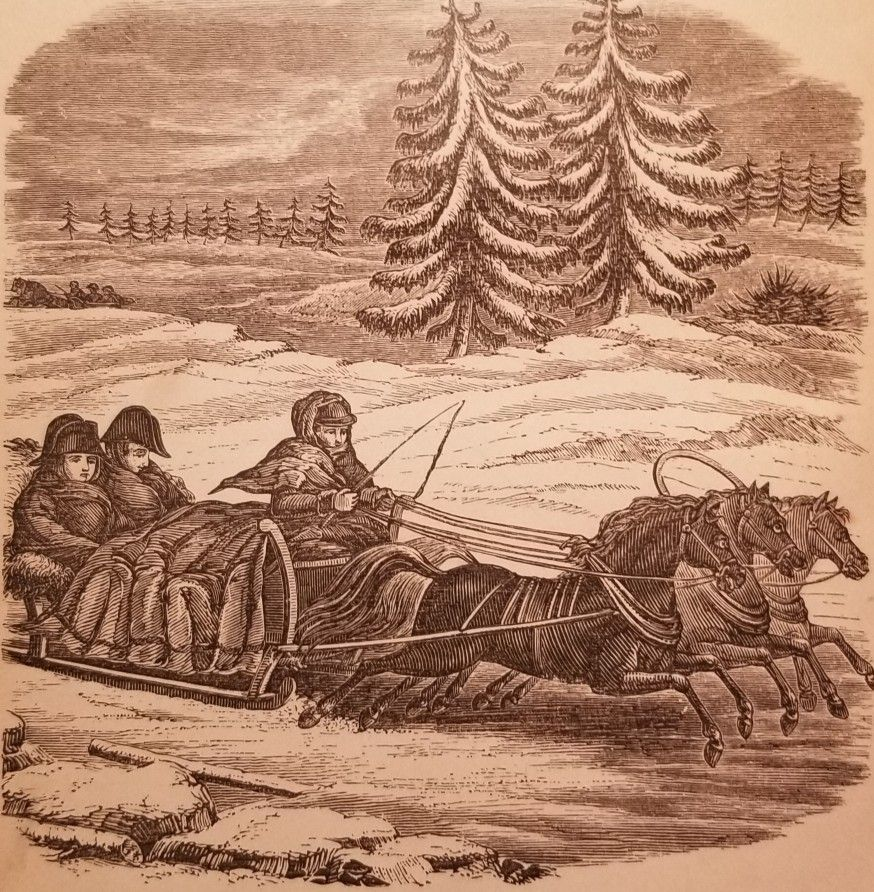

"On the 5th of December, the Emperor, having called together at his headquarters at Smorghoni, the Viceroy, the Prince of Neuchatel, and the Marshals Dukes of Elchingen , Danzig, Treviso,

"On the 5th of December, the Emperor, having called together at his headquarters at Smorghoni, the Viceroy, the Prince of Neuchatel, and the Marshals Dukes of Elchingen , Danzig, Treviso,

the Prince of Eckmuhl, the Duke of Istria, acquainted them that he had nominated the King of Naples his Lieutenant-General to command the army during the rigorous season. His Majesty, in passing through Vilna, was employed several hours with the Duke of Bassano.

His Majesty travelled incognito, in a single sledge, with and under the name of the Duke of Vicenza. He examined the fortifications of Prague, surveyed Warsaw, and remained there several hours unknown.

Two hours before his departure he sent for Count Potocki, and the Minister of Finance of the Grand Duchy, with whom he had a long conference. His Majesty arrived on the 14th, at 1 a.m., at Dresden, from whence he continued his journey to Paris, where he is hourly expected."

To Berthier, he wrote:

"Cousin, I see with sorrow that you did not stop in Vilna for seven or eight days...I hope you will have taken a position on the Pregel; nowhere is it possible to have so many resources as on this line and in Königsberg." (Nap to Berthier, 18 December)

"Cousin, I see with sorrow that you did not stop in Vilna for seven or eight days...I hope you will have taken a position on the Pregel; nowhere is it possible to have so many resources as on this line and in Königsberg." (Nap to Berthier, 18 December)

Napoleon did not seem to know that the hasty exodus from Vilna had been initiated by Murat, not Berthier-whose disposition, as Napoleon himself must have known better than anyone else, obliged him to follow and make the best arrangements possible.

Murat was nearing Königsberg, the residents of which, according to Eugenie, "were under the effervescence of the first news that had reached them." The Oudinots, who had spent the 15th and 16th in the city, were appalled by the "savage conduct" of the Germans.

(More/Replies)

(More/Replies)

Eventually, they were "asked to moderate their cheering out of consideration for a wounded French general officer who had just arrived at the hotel"-Oudinot.

To their dismay, the inhabitants "took no notice of the request, which even seemed to redouble their ardor." (Oudinot)

To their dismay, the inhabitants "took no notice of the request, which even seemed to redouble their ardor." (Oudinot)

Individual accounts give credence to the increasingly palpable animosity of the Prussians. At 3 p.m. on the 18th, 2,000 men of the Imperial Guard were gathered near Hotel de Ville in Wehlau, waiting to be billeted. They were soon greeted by a "big Prussian rascal." (Bourgogne)

Bourgogne and few other men were led into "a room only passably clean," but warm enough. When it was time to leave, the mistress of the house, "nearly six feet high, with a veritable Cossack face," refused to let them go unless they pay "five francs a head for each man." (Ibid)

When Bourgogne objected that "she was a cheat," she taunted him:

"Poor little Frenchman! Six months ago that was all very well-you were stronger; but to-day things are different. You are going to give me what I ask, or I will ...have you taken by the Cossacks!" (Ibid)

"Poor little Frenchman! Six months ago that was all very well-you were stronger; but to-day things are different. You are going to give me what I ask, or I will ...have you taken by the Cossacks!" (Ibid)

This was his last straw, as the sergeant confessed:

"...I caught the woman by the neck to strangle her, but she was stronger; she threw me down upon the straw, and tried, in her turn, to strangle me. Luckily, a kick from one of my comrades made her get up.

"...I caught the woman by the neck to strangle her, but she was stronger; she threw me down upon the straw, and tried, in her turn, to strangle me. Luckily, a kick from one of my comrades made her get up.

Just then the husband came in; but he received a great blow from his dear wife;s fist. She was like a fury, telling him he was no more than a great coward..." In the end, Bourgogne paid the money, swearing that should he come back (he never wanted to), he would get even with her.

In return, the woman spat in his face, and Bourgogne had to be dragged out by his friends to avoid another scuffle.

Marbot wrote that the "Prussians had not forgotten Jena, and the manner in which Napoleon had treated them in 1807 when he dismembered their kingdom."

Marbot wrote that the "Prussians had not forgotten Jena, and the manner in which Napoleon had treated them in 1807 when he dismembered their kingdom."

In this regard, it becomes easy to assess the degree of hypotheticality in the remainder of Napoleon's letter to Berthier:

"I hope that Generals Schwarzenberg an Reynier will have covered Warsaw. Prussia prepares to send reinforcements to cover its territory."

"I hope that Generals Schwarzenberg an Reynier will have covered Warsaw. Prussia prepares to send reinforcements to cover its territory."

Schwarzenberg, on the 18th, was at Białystok, with his right wing covering Narewka-the same marshes he had traversed during his time-consuming pursuit of Sacken in November. Behind him was Reynier, covering the Bug River.

(Wilson)

(Wilson)

In this watershed moment for Napoleon's regime, there was a unit which still remained in the Russian territory: Marshal Macdonald's X Corps, which had long been bifurcated into Yorck's Prussian forces and Grandjean's French division.

Only on this day the marshal received a specific follow-up from the main headquarter-for the first time since autumn!

The letter, delivered by a Prussian officer returning from Vilna, had been witten by Berthier nine days ago:

The letter, delivered by a Prussian officer returning from Vilna, had been witten by Berthier nine days ago:

“The army is at this moment in Vilna and its vicinity. It is, therefore, his Majesty's wish, that you should draw nearer to this new line of operations, and approach Tilsit, for the purpose of covering Königsberg and Dantzig.” (Berthier to Macdonald, Gourgaud)

In his memoir, Macdonald recorded with much astonishment: "On quitting Vilna, Murat at last ordered me to fall back upon Tilsit."

What agitated him more than the sudden news was that the bearer of the dispatch, Major von Schneck, had returned after a lengthy detour from Vilna.

What agitated him more than the sudden news was that the bearer of the dispatch, Major von Schneck, had returned after a lengthy detour from Vilna.

The Prussian officer, "instead of coming direct to [him] as he might have done in thirty hours, followed the high road from Königsberg to Tilsit, Memel, and Mittau."

It was, in Clausewitz's words, "the confirmation of the worst reports."

It was, in Clausewitz's words, "the confirmation of the worst reports."

Macdonald came to a terrible realization that the X Corps had become completely isolated in Mittau, the extreme northern flank. Unbeknownst to him, Wittgenstein had already been ordered to intercept his retreat at Tilsit.

Already, an outpost at Wehrschren was attacked by the Schmidt Freicorps, the Prussian volunteers seething with determination to expel the French from Russia. (Julian Hartwich)

At once, Macdonald ordered preparations to completely evacuate Mittau on the next day. (Macdonald)

At once, Macdonald ordered preparations to completely evacuate Mittau on the next day. (Macdonald)

As Napoleon returned to the Tuileries and the last of the Grande Armée left Russia, another emperor was about to embark on a journey without itinerary.

It was Tsar Alexander, with a burning conviction that his campaign against the behemoth has just started.

It was Tsar Alexander, with a burning conviction that his campaign against the behemoth has just started.

-The End-

@threadreaderapp Unroll!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh