The Upper Midwest was first colonized by New Englanders, “Yankees”. After heroically clearing the land and founding the first towns, Yankee Man vanished. His place was taken by Germans, who have come to dominate the rural Midwest by being everything the Yankee was not.

Maps of US ethnicity today show an impressive German dominance in Midwest counties. What’s interesting about this pattern is that in large part it came about after German immigration had ended. The Germans arrived, rooted themselves to the land and waited for the Anglo to leave.

In 1880 Germans made up only about 10% percent of Midwestern farm workers. Although their immigration fell to low levels after 1890, their control of Midwestern farmland continued to grow throughout the 20th century: there were more German farmers there in 1980 than 1950.

Here you can see the process happening in detail in three east Nebraska counties. Note that the population here peaked in 1890, so what you're seeing is not immigrants swamping Yankees, but rather the Yankees pioneers clearing the land, founding the towns, and then abandoning it

A.B. Hollingshead here describes the process of invasion. Certain invading ethnic groups were more successful than others, with Germans and Czechs being the most effective, Scandinavians an intermediate category, and old Colonial Americans being eager to sell and leave,

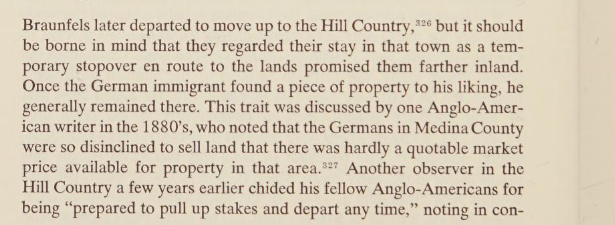

The same process of invasion took place in Nebraska, in Minnesota, even in the Texas Hill Country. In the struggle for living space the German farmer always won, because from his point of view to sell his land was to rob his children.

Sonya Salomon's book Prairie Patrimony refers to German farmers as Yeomen and Yankees as Entrepreneurs. In her typology Yankees behave as perfect capitalists, overseeing large, specialized farms. German farms are fragmented by inheritance, less efficient, but stay in the family

Salamon’s book is based on interviews with central Illinois farmers in the 1980’s. The section on Germans is fittingly blunt: “German farmers are obsessed with land”. They have irrational, romantic ideas about its value that are characteristic of traditional peasant societies.

Salamon’s book is the recent thing available on this subject: is it possible that these cultural differences still exist? My suspicion is that the German Borg is advancing even now, based on the changing demographics of traditionally Norwegian towns I know in Minnesota.

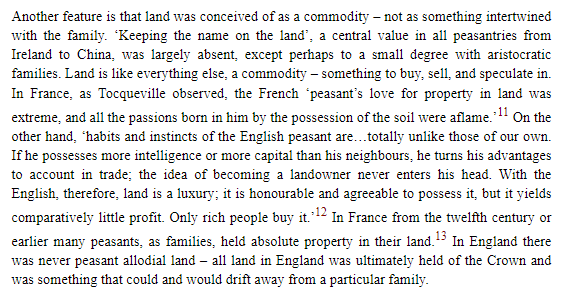

While this description of Germans might make them sound uniquely backward, it’s really the Anglos who are historically anomalous. Economists often find that peasants often pay a “land premium” in traditional societies, in a sense sinking whatever hard won capital they earn.

Remember how Czechs too had that same land hunger in Nebraska? Here Tocqueville, as quoted by Alan Macfarlane, describes the disease affecting his countrymen, as it di alll Europeans in what Jerome Blum called “the servile lands” from France to Russia. The Anglos were different.

When then did Anglos lose that special connection to land? The now famous Gregory Clark argued that no such premium had existed as early as 1560 and that one only emerged very late as an upper class affectation. The root of the Industrial Revolution were planted very, very early

None of this would be any surprise to Alan Macfarlane, who wrote a book arguing that, as far back as good records existed (13th century), the English were not stereotypical peasants. They moved often, their land market was active, and family ties weak. PLEASE read this book.

What happened to the Yankees, then? After selling out in the Midwest they continued to the West Coast and Hawaii, where Yankee men led the rebellions that ended the Hawaiian Kingdom. From East Anglia to Honolulu in 300 years: even the Hawaiians could be impressed by that.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh