Nuclear #fusion will not only come too late to help solve the #climatecrisis. Even in the long run it will not be the unlimited energy source that some are dreaming of. The reason is basic physics, and anyone can do the back-of-envelope calculation. 🧵1/

The problem is that all human energy use ends up as heat. That's no problem now: our current global energy use corresponds to 0.04 Watt/sqm (that's per square metre of Earth surface). The human-caused CO2 increase has a far stronger warming effect: 2.1 W/sqm, following IPCC. 2/

But our energy use (here also in W/sqm) is growing exponentially by 2.3 %/year, 10-fold per century. What does this mean for the future? The Master thesis by Peter Steiglechner @PIK_Climate investigated this in 2018 using a global climate model. Figures taken from his work. 3/

But first, back of envelope: a 10-fold increase in energy use from the current results in a heat flux of 0.4 W/sqm.

With the standard IPCC climate sensitivity that results in 0.3 °C global warming. Oops, now this is a problem, coming on top of greenhouse warming! 4/

With the standard IPCC climate sensitivity that results in 0.3 °C global warming. Oops, now this is a problem, coming on top of greenhouse warming! 4/

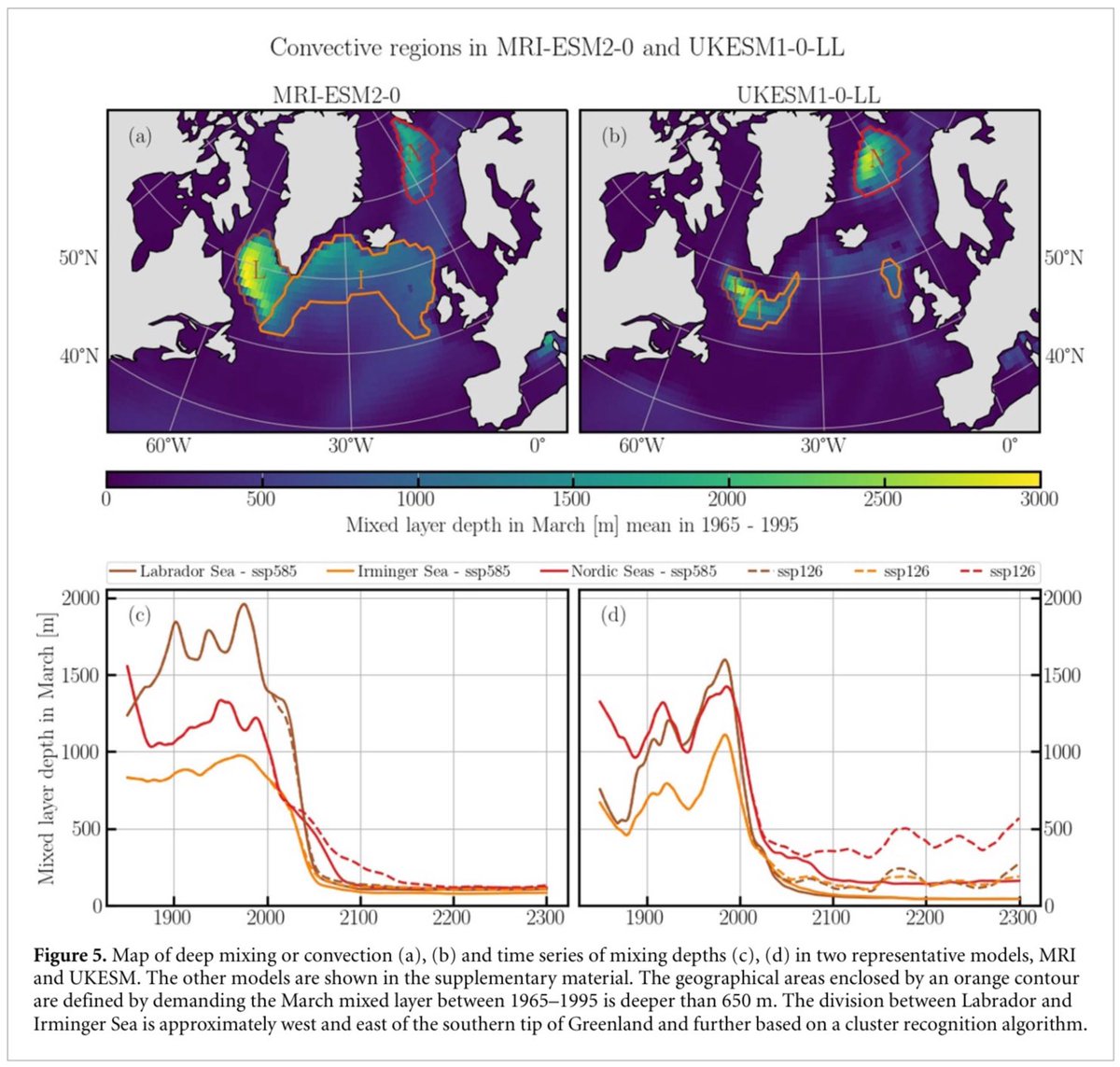

Here's two scenarios to 2100 Peter studied (black lines): 2% increase per year, and a more moderate IPCC scenario called SSP5. That’s less than a ten-fold increase. BUT: the heat release is not globally uniform. Unlike for CO2, it is concentrated where we live, on land. 5/

That is why the (admittedly rather coarse) climate model shows warming concentrated over Northern Hemisphere land, reaching 0.2 – 0.4 °C warming there by 2100 (not even yet in equilibrium). And we’re already struggling to prevent every 0.1 °C of further warming! /6

In terms of heat release, nuclear power (fusion or fission) is just as bad as coal.

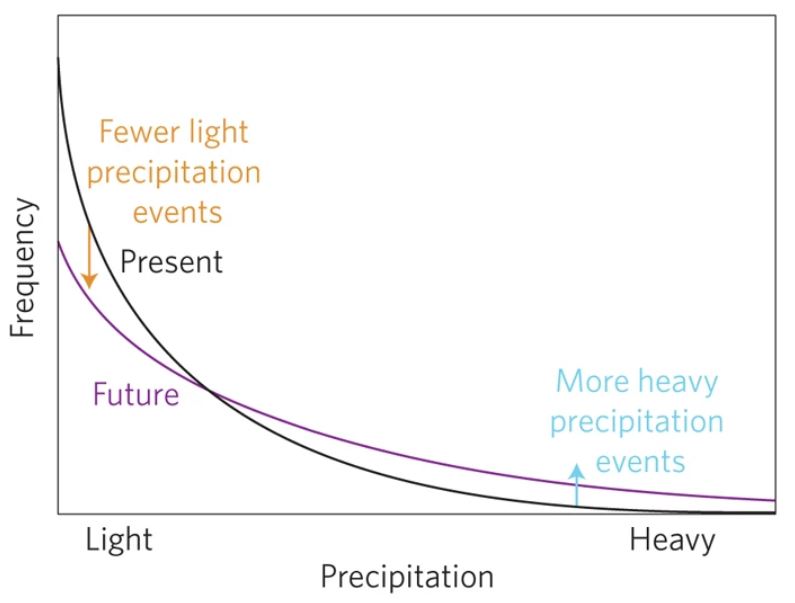

Renewables are different: they use energy from wind, sun, tides or geothermal which is already in the climate system and will end up as heat anyway, whether we use it or not. /7

Renewables are different: they use energy from wind, sun, tides or geothermal which is already in the climate system and will end up as heat anyway, whether we use it or not. /7

(In case you want to say now: but extra heat is radiated into space! This is of course already taken into account. The Earth must get warmer to radiate more, that is what the climate sensitivity describes.) /8

The bottom line is: if humanity wants to use a lot more energy in future, nuclear power can't be the solution. Not just not for the next decades, but also in the long run renewable energies are the only sustainable solution. /9

These technologies we already have, they are growing exponentially and are safe and cheap. (And don't tell me the sun doesn't shine at night - energy system experts already account for that, believe it or not.) /10

https://twitter.com/scienceisstrat1/status/1601650724852895744?s=20&t=b18nkx2Zd8LCvRWMdBVi9Q

A similar argument regarding waste heat was recently made in a peer-reviewed paper in Nature Physics as well. Check it out if you like. /11

nature.com/articles/s4156…

nature.com/articles/s4156…

Link to the Master thesis of Peter Steiglechner: publishup.uni-potsdam.de/frontdoor/inde…

Someone brought up the energy expended in building the plant, incl. mining. For wind power that’s at most a few % of the electricity generated - in this example under 1% for 20y turbine life. Nuclear plants add 300% of the generated power as heat to the 🌍 at 33% efficiency.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh