Early gift for the White House: an absolutely perfect PCE inflation print, with core at 2% (!) target. War is over, if you want it.

Many, including myself, were worried about divergence with CPI; and PCE is what the Fed actually watches. But that didn't happen.

Let's dig in. /1

Many, including myself, were worried about divergence with CPI; and PCE is what the Fed actually watches. But that didn't happen.

Let's dig in. /1

To give a sense of the trend here, let's look at the 3-month core PCE rate. As Powell notes, there had no actual drop throughout the year, all the news cycle events just washing out.

Finally we see a drop. It's just two months, but it's encouraging, especially under the hood. /2

Finally we see a drop. It's just two months, but it's encouraging, especially under the hood. /2

We can break PCE inflation into the three categories that Powell and other Fed officials are watching: goods in deflation, housing peaked, and the rest of services slowing. We see all; notably in services, which has a much different balance of items than CPI. /3

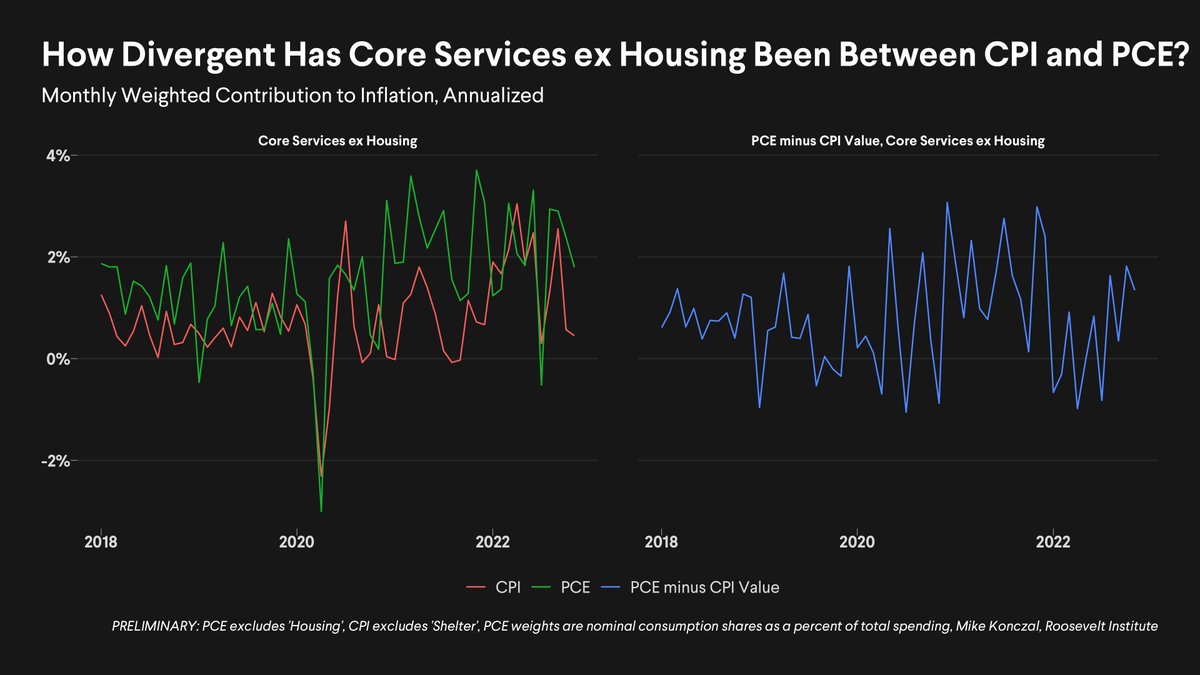

In general, core services ex housing - what Powell watches for wage pressures - runs hotter in PCE than CPI. This divergence jumped this month but had been elevated in 2022.

Digging into this further is an ongoing project (I got covid this week so couldn't prep this, alas). /4

Digging into this further is an ongoing project (I got covid this week so couldn't prep this, alas). /4

Last, services aren't dragged down by imputed prices, a concern @jasonfurman and others have flagged in previous months as falling stock prices are factored into financial services.

Though this happened earlier in the year, the last three months have been in historical norms. /5

Though this happened earlier in the year, the last three months have been in historical norms. /5

Core services still remains elevated versus pre-pandemic trend, and goods won't be in deflation forever. But the trends over the past 3 months are exactly what a "soft landing" would have predicted, and it is important for the Fed to let these positive developments play out. 6/6

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh