This stone tablet from 1800-1600 BC shows that ancient Babylonians were able to approximate the square root of two with 99.9999% accuracy.

How did they do it?

How did they do it?

First, let’s decipher the tablet itself. It is called YBC 7289 (short for the 7289th item in the Yale Babylonian Collection), and it depicts a square, its diagonal, and numbers written around them.

Here is a stylized version.

Here is a stylized version.

As the Pythagorean theorem implies, the diagonal’s length for a unit square is √2. Let’s focus on the symbols there!

These are numbers, written in Babylonian cuneiform numerals. They read as 1, 24, 51, and 10.

These are numbers, written in Babylonian cuneiform numerals. They read as 1, 24, 51, and 10.

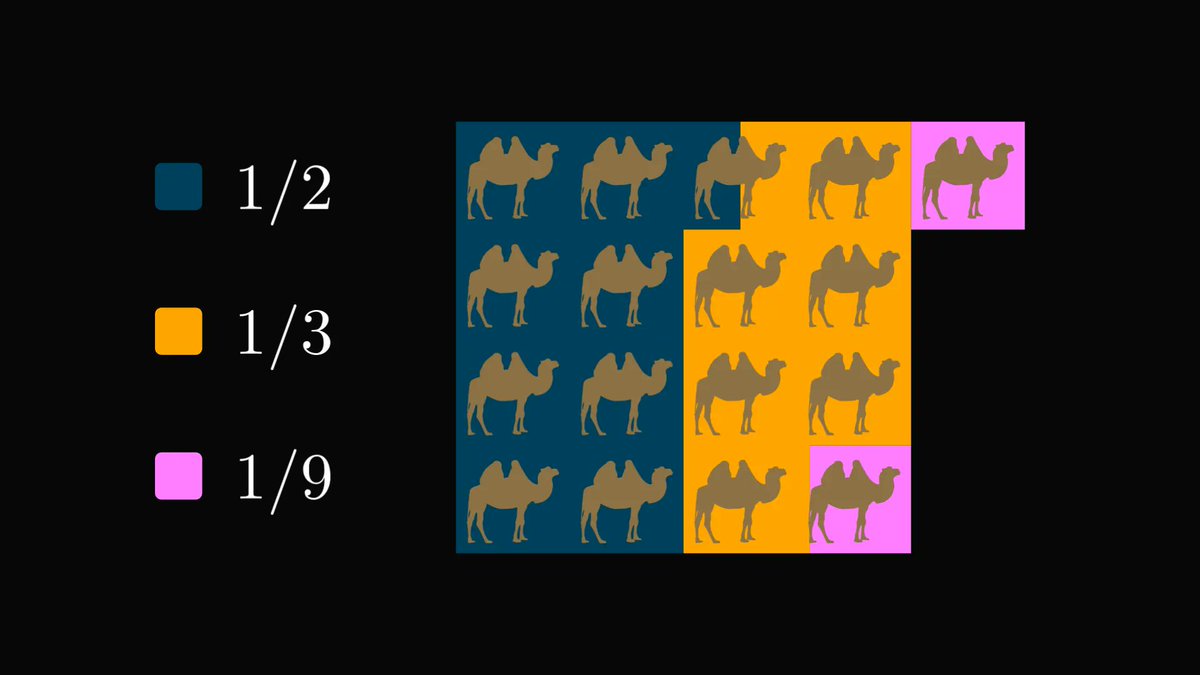

Since the Babylonians used the base 60 numeral system (also known as sexagesimal), the number 1.24 51 10 reads as 1.41421296296 in decimal.

The computational accuracy is stunning. To appreciate this, pick up a pen and try to reproduce this without a calculator. It’s not that easy!

Here is how the ancient Babylonians did it.

Here is how the ancient Babylonians did it.

We start by picking a number x₀ between 1 and √2. I know, this feels random, but let’s just roll with it for now. One such example is 1.2, which is going to be our first approximation.

Thus, the interval [x₀, 2/x₀] envelopes √2.

From this, it follows that the mid-point of the interval [x₀, 2/x₀] is a better approximation to √2. As you can see in the figure below, this is significantly better!

Let's define x₁ by this.

From this, it follows that the mid-point of the interval [x₀, 2/x₀] is a better approximation to √2. As you can see in the figure below, this is significantly better!

Let's define x₁ by this.

Continuing on this thread, we can define an approximating sequence by taking the midpoints of such intervals.

Here are the first few terms of the sequence. Even the third member is a surprisingly good approximation.

If we put these numbers on a scatterplot, we practically need a microscope to tell the difference from √2 after a few steps.

Were the Babylonians just lucky, or did they hit the nail right on the head?

The latter one. If you are interested in the details, check out the full version of the post here: thepalindrome.substack.com/p/how-did-the-…

The latter one. If you are interested in the details, check out the full version of the post here: thepalindrome.substack.com/p/how-did-the-…

If you have enjoyed this explanation, share it with your friends and give me a follow! I regularly post deep-dive explainers such as this.

https://twitter.com/TivadarDanka/status/1608419325706391554

One more thing. The YBC 7289 tablet is actually clay, not stone.

This is my secret engagement tactic: I plant a simple error, then let others point it out.

(Just kidding. Seriously though, I always let a silly mistake through the cracks accidentally.)

This is my secret engagement tactic: I plant a simple error, then let others point it out.

(Just kidding. Seriously though, I always let a silly mistake through the cracks accidentally.)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh