#OTD 30 December, 1812, Major-General Diebitsch and General Yorck signed the Convention of Tauroggen, drafted by Major von Clausewitz. It stipulated the Prussian army to declare neutrality and terminate their service for Marshal Macdonald.

#Voicesfrom1812

#Voicesfrom1812

After three days of stalled negotiations, Clausewitz succeeding in escalating his final bargain with Yorck at Tauroggen into a conference “confined to pure Prussians.”

As scheduled, Yorck and Diebitsch met at 8 a.m. on the 30th, at “the mill of Poscherun.”

(Clausewitz)

As scheduled, Yorck and Diebitsch met at 8 a.m. on the 30th, at “the mill of Poscherun.”

(Clausewitz)

Yorck appeared with Colonel von Roeder, his Chief of Staff, and Major von Seydlitz, his first aide-de-camp who had come all the way from Berlin on the 29th without any knowledge of what was about to transpire. The Major, nevertheless, was the right man for the occasion.

Much to the counterparty’s delight, Seydlitz’s hatred of the French surpassed that of Yorck’s. “[S]trongly under the conviction that it was both in the power and the duty of Prussia to throw of the French yoke at this moment,” he embodied the public opinion in Berlin.

Diebitsch, accompanied by Clausewitz and Count Dohna, arrived next. The strange assembly of Prussians wasted no time beating around the bush.

Yorck, although certain that “he was incurring still great hazard” before his king, signed the seven-point convention stipulating:

Yorck, although certain that “he was incurring still great hazard” before his king, signed the seven-point convention stipulating:

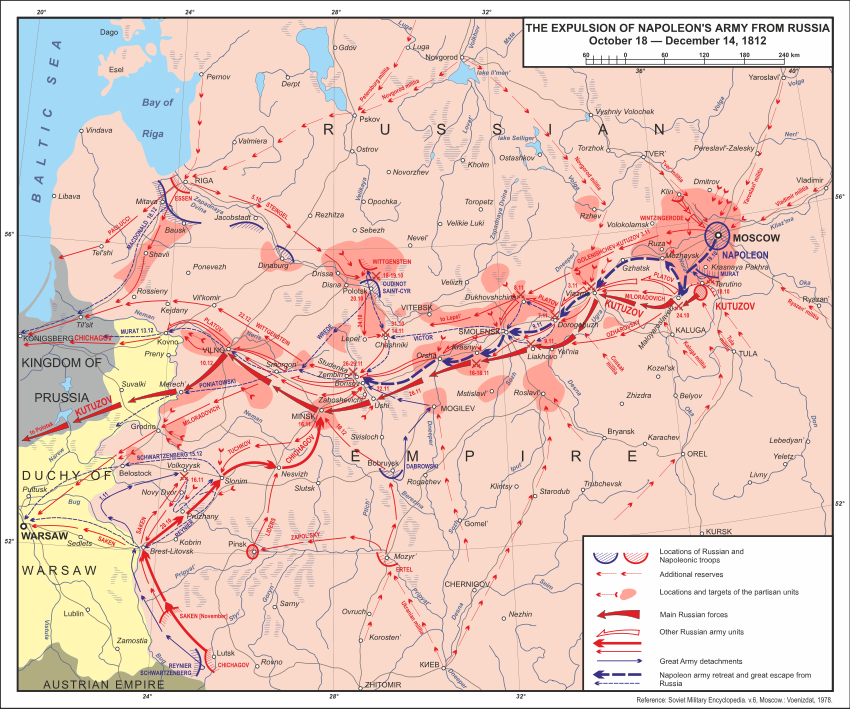

1. The Prussians were entitled to trespass, without the right to take up quarters, the territory from Memel and Nimmerstat to Woinuta and Tilsit, and that from Tilsit to Schilliapischken, Melankew, and Lobinau-the points under direct threat from Wittgenstein’s advance.

2. The Prussians shall remain neutral in the area designated in Article no.1 until the arrival of orders from His Majesty, the King of Prussia. In case of orders to rejoin the French, the Prussians shall not engage in combat with the Russians for…one month from this date.”

3. “In case of His Majesty, the King of Prussia, or His Majesty, the Emperor of Russia, refusing the ratify this convention, the Prussian corps shall be free to carry itself where the orders of their king call them.”

(The Convention of Tauroggen, 30 December 1812, Nafziger)

(The Convention of Tauroggen, 30 December 1812, Nafziger)

4. The Prussian prisoners and equipment detained by Palucci “along the main route to Mittau” were to “cross without obstacles through the Russian lines to rejoin the Prussian Corps.”

5. Should Massenbach receive Yorck’s order, the articles shall be applicable to his troops.

(Ib.

5. Should Massenbach receive Yorck’s order, the articles shall be applicable to his troops.

(Ib.

For No. 5, Yorck had already made the necessary arrangements. A courier was racing toward Tilsit, where Massenbach was in an uneasy coexistence with Macdonald. He had six battalions and three squadrons, and another seven squadrons detached to Bachelu’s vanguard.

(Clau.)

(Clau.)

6. Likewise, all the prisoners captured by Diebitsch from Massenbach’s forces “shall equally be included in this convention.” This must have included those captured in the final skirmish waged by the X Corps near Piktupöhnen on the 26th.

7. “The Prussian Corps shall conserve the right to concert all that is relative to its provisionment with the provincial regencies of Russia. This case is not excepted when those provinces are occupied by Forces.” In this way, 2/3 of the X Corps were granted a safe passage.

Yorck, whose heart was trembling at “so bold a step” which would have met “a direct declaration against it” in Berlin, signed the Convention of Tauroggen. Clausewitz, in his account, extolled Diebitsch’s efforts to reassure his compatriot weighed down with guilt:

“The conduct of General Diebitsch throughout the transaction was most praiseworthy; in evincing towards General Yorck as much confidence as his own responsibility allowed him, in displaying throughout an unprejudiced, frank, and noble bearing,

and appearing to feel only for the common interest, and as much for Prussia as for Russia, in rejecting all appearance of superiority in arms, all pride of victory, and all appearance of either Russian vanity or rudeness,

he facilitated to General Yorck the execution of a task very difficult in itself, and which under conditions less favorable would probably not have been brought to maturity.” (Clau.)

Yorck hastened to communicate to all the (potential) stakeholders in the secret agreement.

Yorck hastened to communicate to all the (potential) stakeholders in the secret agreement.

His priority was to safeguard the Article no. 3. Writing to King Frederick William III, he chose his words carefully to emphasize the demanding conditions imposed by Macdonald:

“Placed in a very unfavorable position by setting out at a later day than the marshal did,

“Placed in a very unfavorable position by setting out at a later day than the marshal did,

and being ordered to march from Mitau to Tilsit, for the sole purpose of covering the retreat of the VII Division, I have been compelled, on account of impassable roads, and very severe weather, to conclude with the Russian commander..which I beg leave to lay before Your Majesty.

Firmly convinced that a continuation of the march would have unavoidably brought about the dissolution of the whole corps...as was the case of the retreat of the Grand Army, I believe it was incumbent upon me, as your majesty's faithful subject, to regard your interest,

and no longer that of your ally, for whom our auxiliary corps would only have been sacrificed without being able to afford him any real assistance in the desperate predicament in which he was placed.

...I would willingly lay my head at the feet of your majesty if I have erred;

...I would willingly lay my head at the feet of your majesty if I have erred;

I would die with the joyous conviction of having at least committed no act contrary to my duty as a faithful subject and a true Prussian. Now or never is the time for your majesty to extricate yourself from the thralldom of an ally,

whose intentions in regard to Prussia are veiled in impenetrable darkness , and justify the most serious alarm. That consideration has guided me. God grant it may be for the salvation of the country!"

(Johann Gustav Droysen, Luise Mühlbach)

(Johann Gustav Droysen, Luise Mühlbach)

Major von Henkel, one of Frederick's aides-de-camp sent to Berlin on the 26th, had given the King "prelimianary knowledge."

Now, to expose that the bilateral agreement has become irreversible, Major von Thile was sent to Berlin with the letter and a copy of the convention.

Now, to expose that the bilateral agreement has become irreversible, Major von Thile was sent to Berlin with the letter and a copy of the convention.

Yorck's second dispatch was intended for his (former) superior in Tilsit, who "did not yet venture to appear

suspicious of a defection."

The Marshal, despite his personal incompatibility with Yorck, felt obliged not to desert him under all circumstances.

(Segur)

suspicious of a defection."

The Marshal, despite his personal incompatibility with Yorck, felt obliged not to desert him under all circumstances.

(Segur)

One of his letters on the 30th read:

"I am lost in conjectures. If I retreat, what would the Emperor say? what would be said by France, by the army, by Europe? Would it not be an indelible stain on the X Corps, voluntarily to abandon a part of its troops,

(More/Replies)

"I am lost in conjectures. If I retreat, what would the Emperor say? what would be said by France, by the army, by Europe? Would it not be an indelible stain on the X Corps, voluntarily to abandon a part of its troops,

(More/Replies)

and without being compelled to it otherwise than by prudence? Oh, no; whatever may be the result, I am resigned, and willingly devote myself as a vicitm, provided that I am the only one." (Segur)

Clausewitz could not help but praise how Macdonald "behaved himself very nobly."

Clausewitz could not help but praise how Macdonald "behaved himself very nobly."

Yorck, citing the same reasons, wrote to the Marshal:

"Notwithstanding fatiguing marches to join your Excellency, it was impossible for me to avoid compro- mising my flanks and rear; and I had no alternative but either to sacrifice the greater part of my troops,

"Notwithstanding fatiguing marches to join your Excellency, it was impossible for me to avoid compro- mising my flanks and rear; and I had no alternative but either to sacrifice the greater part of my troops,

and all the material on which their subsistence depended, or to save the whole by making a convention which permits me to collect the Prussians in a part of the territory of Prussia now in the power of the Russians in consequence of tlie retreat of the French army."

(Wilson)

(Wilson)

Emphasizing that his decision has been guided by "the purest motives," he declared that his army will form "a neutral body" and henceforth free of all obligations to Napoleon and France.

(Wilson)

(Wilson)

In the evening, Massenbach received "a positive order," from Yorck, "for his return from Tilsit to the main body." He also read a transcript of the convention attached to the letter.

The time seemed most opportune for an overnight escape.

The time seemed most opportune for an overnight escape.

Grandjean and Macdonald's quarters were at some distance from his, while Bachelu's vanguard was still at Regnitz.

But he was soon stopped by the news of the return of Heudelet's division from Königsberg and Bachelu's from Regnitz.

But he was soon stopped by the news of the return of Heudelet's division from Königsberg and Bachelu's from Regnitz.

Believing that "these arrivals might be directed against himself," Massenbach decided to give up his initial plan. Clausewitz commented that his caution was rather excessive, for Heudelet's regiments had stumbled into Tilsit "accidentally."

(Clausewitz)

(Clausewitz)

Napoleon's letter to Clarke, dated on the same day, confirms this claim. He ordered that Heudelet and Loison's divisions, the reserve forces of Augereau's XI Corps, should remain where they are.

They were to guard the Vistula-now open to the Russians-on its right.

They were to guard the Vistula-now open to the Russians-on its right.

As for the rest the French in Königsberg, they were only a small cluster defending Murat's headquarter. On the 30th, Napoleon sent a reply to Berthier, one of the refugees in the town:

"I have received your note upon the real losses, over which I shall think seriously...

"I have received your note upon the real losses, over which I shall think seriously...

I have just raised 15,000 cavalry and 8,000 artillery horses, in addition to 4,000 animals for the military train...There is a good deal of war material in Prussia, in Danzig, and the other places.

Eblé should pay attention to this. The conscription is excellent this year..."

Eblé should pay attention to this. The conscription is excellent this year..."

The rest of the army was scattered in garrisons on the road to the Vistula, like Eugene at Marienwerder, to whom Napoleon wrote:

"I have received your letter of the 20th. I am sorry to see that the cold is so intense. I am very anxious to learn the real condition of the army."

"I have received your letter of the 20th. I am sorry to see that the cold is so intense. I am very anxious to learn the real condition of the army."

Moreover, a part of Bachelu's vanguard consisted of Prussians soldiers who, as Segur revealed, had already been informed of the convention.

At 8 p.m., when the French general called for a return to Tilsit, the Prussian colonels "refused to mount their horses."

At 8 p.m., when the French general called for a return to Tilsit, the Prussian colonels "refused to mount their horses."

They brought up every pretext until they, like their two irreconcilable but equally magnanimous generals, felt that they "could not resolve to betray him" in the middle of the road.

At 2 a.m. on the 31st, they arrived at Tilsit, now "fully prepared to abandon" him.

(Segur)

At 2 a.m. on the 31st, they arrived at Tilsit, now "fully prepared to abandon" him.

(Segur)

"These small accidents, which were rather comic than tragic, only made us laugh, and restored to us the gaiety to which had so long been strangers," wrote Lejeune after burying his face in the snow several times.

He had just left Danzig with his sister and General Vasserot in a sledge, which was repetitively overturned by "a tremendous storm" on the day.

The artist had no idea that the Duchy of Warsaw his sledge was flying into was no longer a safe haven for the retreating.

The artist had no idea that the Duchy of Warsaw his sledge was flying into was no longer a safe haven for the retreating.

So was Bourgogne, well-rested with his friends Grangier and Picart at Wilbalen since the 17th. He had been nursed by Madame Gentil, a pretty German woman married to a former French Hussar.

The trio cackled after pretending to weep at a funeral for the sake of food.

The trio cackled after pretending to weep at a funeral for the sake of food.

They tried not to laugh when a lady called them "first-rate fellows" to be "served at once."

He spent the evening curiously observing fourteen women in mourning, clad in black and smoking pipes, a common sight in the country especially among the sailors' wives.

(Bourgogne)

He spent the evening curiously observing fourteen women in mourning, clad in black and smoking pipes, a common sight in the country especially among the sailors' wives.

(Bourgogne)

-The End-

Have a great weekend people.

Have a great weekend people.

@threadreaderapp Unroll.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh