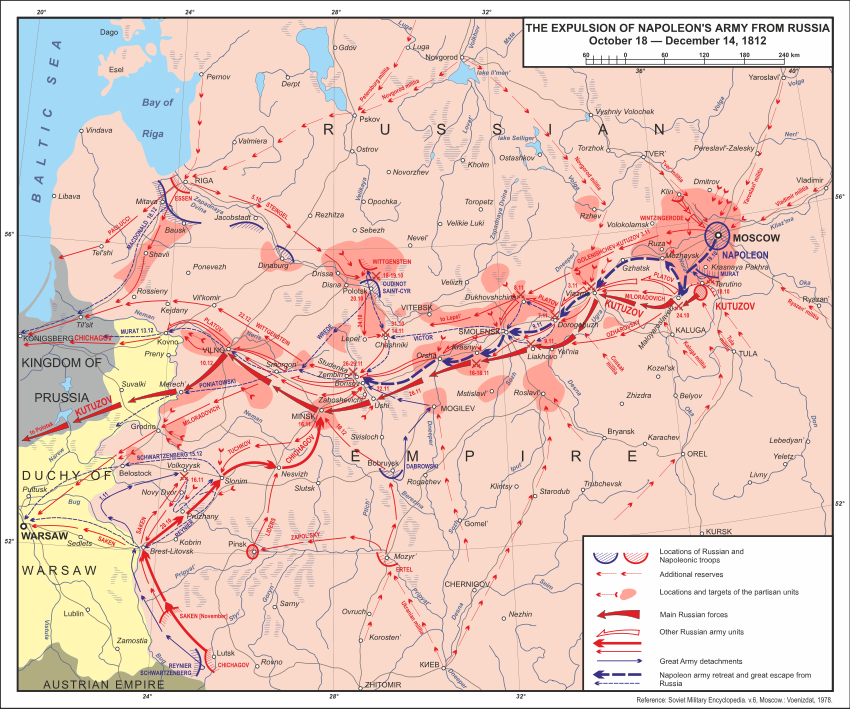

#OTD 31 December, 1812, on New Year’s Eve, Yorck and Massenbach left Tilsit to join Diebitsch. Macdonald, finding his corps suddenly reduced to a third, recommenced the retreat.

Eblé, the savior of the Grande Armée at the Berezina, died in Königsberg.

#Voicesfrom1812

Eblé, the savior of the Grande Armée at the Berezina, died in Königsberg.

#Voicesfrom1812

At daybreak, Massenbach informed the French that he would "occupy...the tête du pont" across the Neman. (Wilson)

His battalions, so uniform in their "enthusiastic acclamation," marched out of Tilsit, crossing the Memel River at 8 a.m. to effect a junction with Diebitsch. (Cl.)

His battalions, so uniform in their "enthusiastic acclamation," marched out of Tilsit, crossing the Memel River at 8 a.m. to effect a junction with Diebitsch. (Cl.)

The general, refusing to compromise his honor, left Macdonald a letter revealing the truth of the matter. Attached to the order from Yorck on the 30th, it read:

"The letter of General Yorck will have already in- formed your Excellency that my course of action is prescribed,

"The letter of General Yorck will have already in- formed your Excellency that my course of action is prescribed,

and that I can make no change, as the measures of precaution taking by your Excellency lead me to suspect an intention to retain me by force, or to disarm my troops. I have been obliged to adopt the line I have pursued to bring myself under the convention,

that the Commanding General has signed, who has sent me this morning the notice and instructions for my conduct.

Your Excellency will pardon my not presenting myself to acquaint you of the proceeding I am directed to execute,

Your Excellency will pardon my not presenting myself to acquaint you of the proceeding I am directed to execute,

for the respect and esteem I shall ever preserve for your Excellency might have prevented me from a discharge of my duty." (Massenbach to Macdonald, 31 December 1812, Wilson)

The letter would not reach the recipient until the next day.

The letter would not reach the recipient until the next day.

Macdonald quelled his mounting suspicions until the last minute. But, as he wrote, "Four days had already passed in uneasiness, impatience, and, I must almost say, anguish."

His Prussian sentinels parroted that "they had neither seen nor heard of General Yorck."

(Macdonald)

His Prussian sentinels parroted that "they had neither seen nor heard of General Yorck."

(Macdonald)

By this time, the French generals began whispering about their ally’s betrayal. Some of them pointed out that the Prussians were looking increasingly nervous in their presence, especially after the arrival of “a Count von Brandenburg, a natural brother of the King.”

(Ibid)

(Ibid)

Macdonald, however, abstained from joining them. Trustful to a fault, he retorted to one of the vigilant officers:

“If they have orders, or if they take upon themselves to abandon our cause, what hinders or prevents them?”

(Ibid)

“If they have orders, or if they take upon themselves to abandon our cause, what hinders or prevents them?”

(Ibid)

Even if Yorck had left him, Macdonald insisted to himself, that “some obstacle, sudden panic,” not treason, “might have determined the general to retrace his steps.” And the Prussians would be the last ones to “drive their cowardice to the extremity of giving us up.”

(Ibid)

(Ibid)

Macdonald regretted being trustful to a fault:

“Had I been less confident in other people’s honour, the attitude of the Prussians would have opened my eyes to what was going on around me.”

He turned away from “stories…of ill-will, and even of insubordination and disobedience.

“Had I been less confident in other people’s honour, the attitude of the Prussians would have opened my eyes to what was going on around me.”

He turned away from “stories…of ill-will, and even of insubordination and disobedience.

Several times he swore before his entourage in Tilsit:

“I would remain firm in my resolution; that my life and career should never have to bear upon them the blot of having abandoned, on account of fears which were perhaps imaginary, the troops committed to my care;

“I would remain firm in my resolution; that my life and career should never have to bear upon them the blot of having abandoned, on account of fears which were perhaps imaginary, the troops committed to my care;

and that, under any circumstances, I was determined to risk everything, even to recross the Niemen to go in search of the rear-guard, rather than voluntarily separate myself from them by quitting the banks of the river.“

But four days had passed in ominous silence.

But four days had passed in ominous silence.

It was already the last night of the 1812 when reports of enemy movements nearby flowed into the headquarter.

Acutely aware that he could no longer prolong his inactivity, Macdonald sent out Bachelu’s vanguard on a reconnaisance mission.

Acutely aware that he could no longer prolong his inactivity, Macdonald sent out Bachelu’s vanguard on a reconnaisance mission.

The men, consisting of the French and Prussians, marched toward Schillupischken on the road to Insterburg. Under Macdonald’s order to be “ready to take up arms at the first signal,” they left their bivouac at dark.

The weather, according to Macdonald, was “very bad.”

The weather, according to Macdonald, was “very bad.”

Despite the incipient danger, the Marshal himself chose to remain in Tilsit, as he recounted:

“‘They will carry you off!’ someone said to me.

‘Let us go!’

‘No,’ I replied; ‘I prefer to risk it.’”

Between 11 p.m. and midnight, his faith in his ally was shattered.

“‘They will carry you off!’ someone said to me.

‘Let us go!’

‘No,’ I replied; ‘I prefer to risk it.’”

Between 11 p.m. and midnight, his faith in his ally was shattered.

The commander of a Prussian battalion suddenly came up to him, announcing “that he had received orders from General Massenbach…to get under arms.”

Bachelu, too, found his course blocked by his own Prussians who “refused to obey and march.”

(Ibid)

Bachelu, too, found his course blocked by his own Prussians who “refused to obey and march.”

(Ibid)

If time was not on his side, the enemy was; General Scheppelow, in command of Wittgenstein’s vanguard, “had, by a mistake…marched on the 31st to Szillen, instead of Schillupischken, situated on the road from Tilsit to Insterburg.”

(Clausewitz)

(Clausewitz)

While Macdonald struggled to make sense of the turn of events, Königsberg was thrown into a mourning.

Eblé, who had perservered to save the army at Berezina until the inevitable destruction of the bridge, came to share the same fate as his Dutch pontonniers.

Eblé, who had perservered to save the army at Berezina until the inevitable destruction of the bridge, came to share the same fate as his Dutch pontonniers.

Planet de la Faye, two days before leaving Königsberg, had visited the general, whom he had known for a long time.

Eblé looked “completely demoralized” and did nothing but to show him “the waistband of his trousers, which had become too wide” for his body withered from cold.

Eblé looked “completely demoralized” and did nothing but to show him “the waistband of his trousers, which had become too wide” for his body withered from cold.

Napoleon was planning to appoint Eblé to Commander of the Guard Artillery after Lariboisière, who had had his last day in Königsberg.

The succesor-to-be, however, became too “smitten by a mortal disease at the Berezina.”

(Planat de la Faye, Thiers)

The succesor-to-be, however, became too “smitten by a mortal disease at the Berezina.”

(Planat de la Faye, Thiers)

On the New Year’s Eve, fresh deaths coexisted with vibrant desire to start life anew.

John Quincy Adams wished:

“For myself, may the divine energies be granted to perform fully all my duties to God, to my fellow mortals in all the relations of life, and to my own soul!”

John Quincy Adams wished:

“For myself, may the divine energies be granted to perform fully all my duties to God, to my fellow mortals in all the relations of life, and to my own soul!”

Sergeant Bourgogne wondered what to give Madame Gentil as a New Year’s gift.

He decided to sleep on it:

“I resolved to get up early, and see if I could not find something among the Jews.”

He decided to sleep on it:

“I resolved to get up early, and see if I could not find something among the Jews.”

-The End-

HAPPY NEW YEAR, HAPPY 2023 and 1813 🎉🎉🎉❄️🎉🎉❄️❄️❄️❄️❄️🎉🎉

HAPPY NEW YEAR, HAPPY 2023 and 1813 🎉🎉🎉❄️🎉🎉❄️❄️❄️❄️❄️🎉🎉

@threadreaderapp Unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh