One pretty prevalent critical view of the #Exodus narratives, proposed by Redford, but popularised by #IsraelFinkelstein, is that - though they may hold some earlier memories - they were written in the 7th century, and basically reflect the 7th c Egyptian context.

Much could be said in response to this rather depressing claim (and has been by, e.g., Hoffmeier)

A recently finished PhD gives a bit more data relating to this question, and suggests that the Redford-Finkelstein position doesn't really fit the facts.

A recently finished PhD gives a bit more data relating to this question, and suggests that the Redford-Finkelstein position doesn't really fit the facts.

Ella Karev's PhD thesis examines what kinds of slavery were dominant in Egypt between 900BC and 330BC.

Google the title and you can download it for yourself:

"Slavery and Servitude in Late Period Egypt (c. 900 – 330 BC)"

Google the title and you can download it for yourself:

"Slavery and Servitude in Late Period Egypt (c. 900 – 330 BC)"

Karev found that slavery in Late Period tended to be

* small scale

* family-based (rather than property of the crown)

* generally enslavement of Egyptians, rather than foreigners.

* small scale

* family-based (rather than property of the crown)

* generally enslavement of Egyptians, rather than foreigners.

So, to go back to Finkelstein's view: if the 7th c Judean elite had decided to take a study-vacation down to Egypt to get some background for their new thriller novel: 'Exodus: the Pharaoh's Downfall', they would have found mainly Egyptian slaves, working for private individuals.

So, at least with respect to the issue of slavery, the Exodus narratives as we have them do *not* seem to fit the 7th century BC Egyptian context.

But they *do* fit the 13th century BC context extraordinarily well:

But they *do* fit the 13th century BC context extraordinarily well:

In the New Kingdom in Egypt (v. roughly 1500-1000) slaves were:

* very common

* very often from the Levant region (Israel/Palestine - Syria)

* very often set to work on crown-controlled building projects (like the Abu-Simbel temple pictured below, commissioned by Ramesses II)

* very common

* very often from the Levant region (Israel/Palestine - Syria)

* very often set to work on crown-controlled building projects (like the Abu-Simbel temple pictured below, commissioned by Ramesses II)

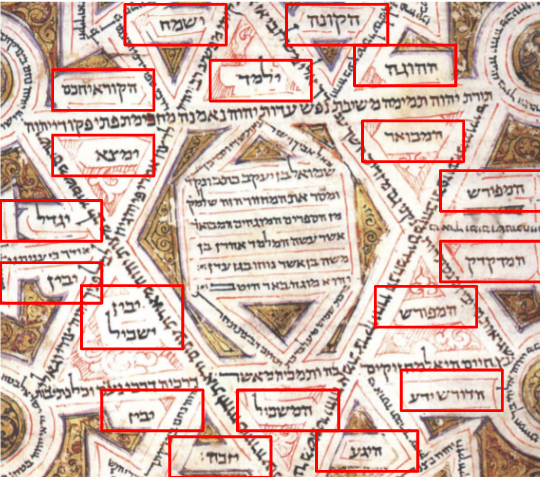

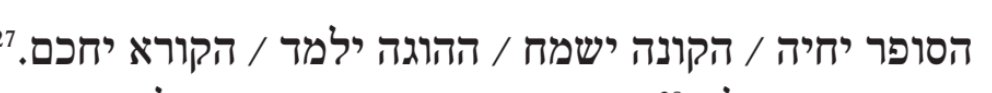

In fact, even some of the most detailed elements in the Exodus narratives seem to fit what we know about Egyptian slavery in the New Kingdom era.

Like the fact that Levantine slaves were set to work making mud bricks, as I wrote a little about here:

academic.tyndalehouse.com/explore/articl…

Like the fact that Levantine slaves were set to work making mud bricks, as I wrote a little about here:

academic.tyndalehouse.com/explore/articl…

TLDR:

With regard to the issue of slavery in Egypt:

The Exodus narratives do NOT resemble reality in Egypt in the 7th century BC.

The Exodus narratives DO resemble reality in Egypt in the 13th century BC - remarkably well.

With regard to the issue of slavery in Egypt:

The Exodus narratives do NOT resemble reality in Egypt in the 7th century BC.

The Exodus narratives DO resemble reality in Egypt in the 13th century BC - remarkably well.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh