What book did the most damage to International Relations as an academic discipline and why is it "Clash of Civilizations"?

[THREAD]

[THREAD]

This 🧵 is my answer to a great question posed by @HistoryNed 👇 (&, based on the comments, "Clash" is the answer of several others as well).

https://twitter.com/HistoryNed/status/1616092346373783553

I'm sure many are familiar with "Clash of Civilizations" (and I've already written a few 🧵s about it, which I'll draw on here).

Nevertheless, let's quickly review it before talking about why it's done damage to IR.

Nevertheless, let's quickly review it before talking about why it's done damage to IR.

Samuel Huntington wrote an article for @ForeignAffairs in 1993 with the title (ending in a `?') ...

foreignaffairs.com/articles/unite…

foreignaffairs.com/articles/unite…

...and then wrote a 1996 book with the same title (though no more `?').

amazon.com/Clash-Civiliza…

amazon.com/Clash-Civiliza…

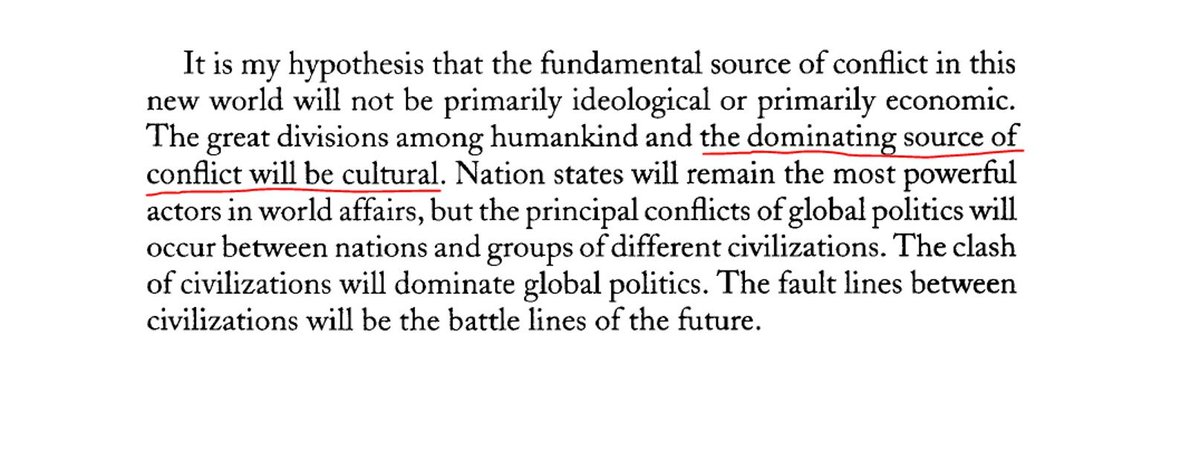

In the Foreign Affairs article, Huntington states his argument very clearly: in the post-Cold War world, the dominate sources of conflict will not be ideological or economic, but cultural.

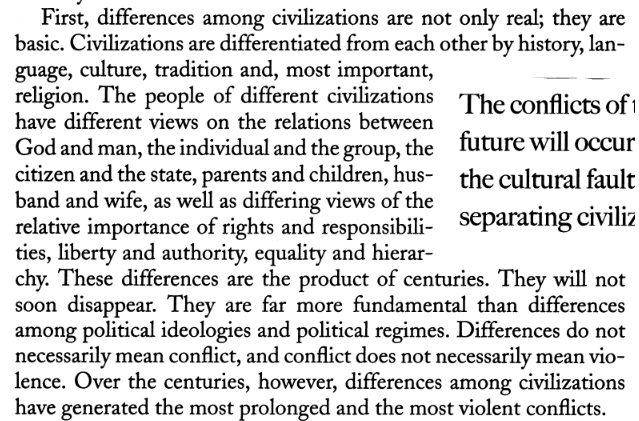

"Cultural" can mean a variety of things (we'll come back to that), though he emphasizes religion, labeling it "most important".

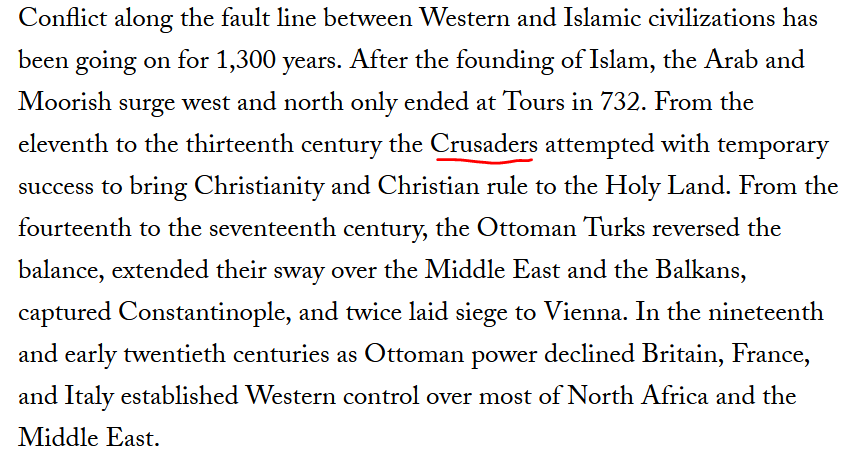

Though his claims are about the post-Cold War World, Huntington uses a variety of historical examples to support his points, such as (you guessed it) The Crusades.

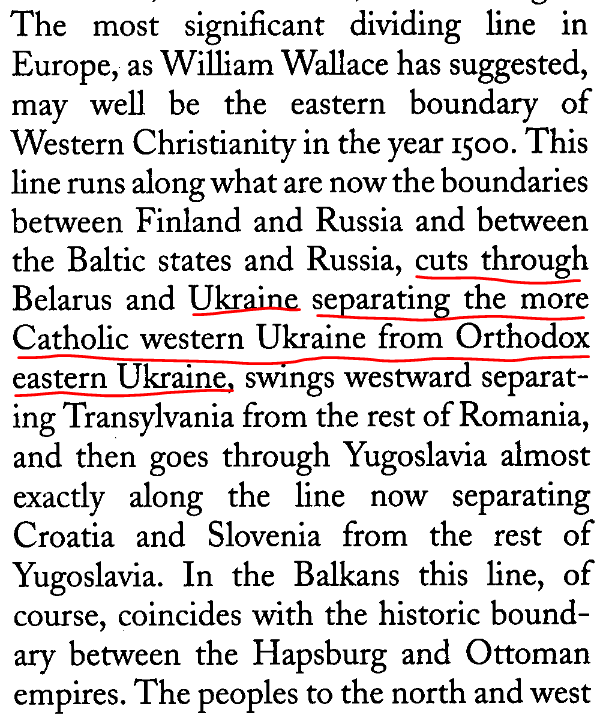

He also offers a specific prediction about the post-Cold War world: that the significant "dividing line" will be between Western Christianity and Eastern Orthodoxy, which divides Ukraine.

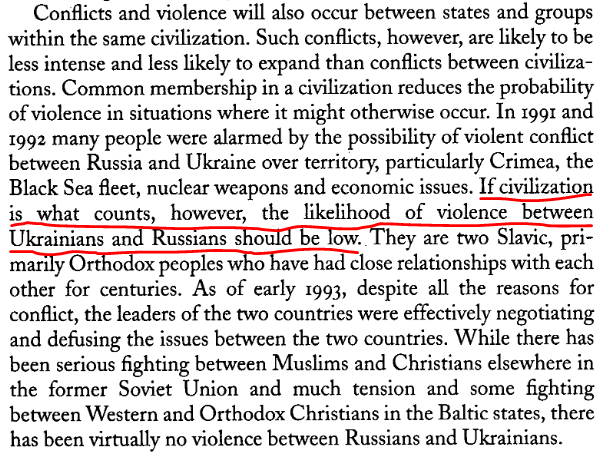

Which leads Huntington to predict peace between Ukraine and Russia (in contrast to more state-based "realist" arguments).

Of course, he was wrong in this prediction, which I elaborate upon in this recent @ForeignAffairs piece.

foreignaffairs.com/articles/ukrai…

foreignaffairs.com/articles/ukrai…

The 1996 book offers an expansion on his claims. There isn't much "new" in the book compared to the article.

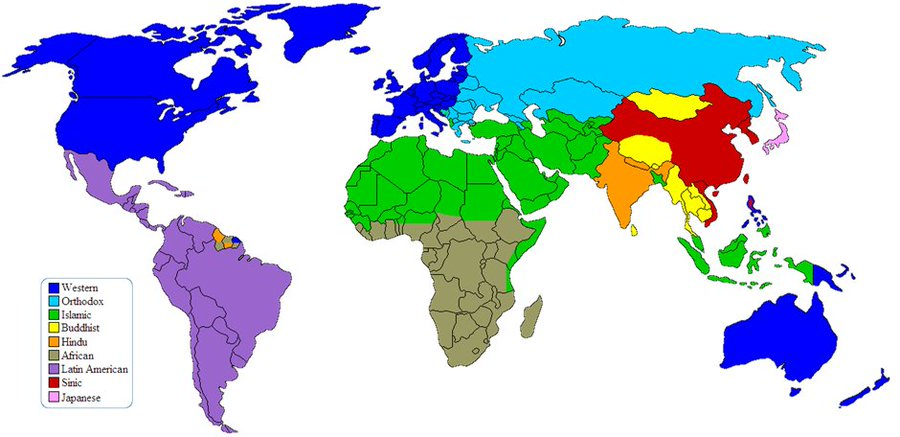

But one BIG new thing is Huntington's attempt to classify civilizations, which he does with this map.

But one BIG new thing is Huntington's attempt to classify civilizations, which he does with this map.

It seems that Huntington based his coding on Arnold Tonybee's "A Study of History". Huntington says that of the 21 civilizations identified by Tonybee, only 6 exist today (though Huntington's map has 9 civilizations identified).

amazon.com/History-Toynbe…

amazon.com/History-Toynbe…

There are LOTS of criticisms to make of this map (see below), but at least it offered a basis for testing Huntington's claims. Scholars did just that, most notably Errol Henderson in a series of articles and then this 2020 book (co-authored w/ Zeev Maoz).

amazon.com/Scriptures-Shr…

amazon.com/Scriptures-Shr…

The consistent finding from such work? No evidence for the Clash of Civilizations even when using Huntington's own data.

journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.117…

journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.117…

So that's the Clash of Civilization's thesis.

Why has it done damage, especially since it's been shown wrong time and again?

To answer that, let's first return to Huntington's map.

Why has it done damage, especially since it's been shown wrong time and again?

To answer that, let's first return to Huntington's map.

As pointed out above, it's not fully clear the basis of Huntington's coding of "Civilization".

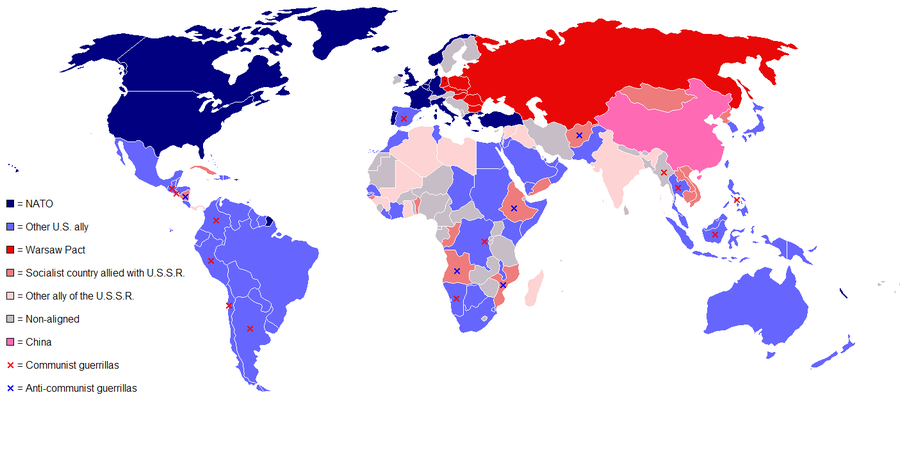

I mean, Huntington's map of looks like a Cold War world map. This was pointed out by Peter Katzenstein...

I mean, Huntington's map of looks like a Cold War world map. This was pointed out by Peter Katzenstein...

...in this edited volume.

amazon.com/Civilizations-…

amazon.com/Civilizations-…

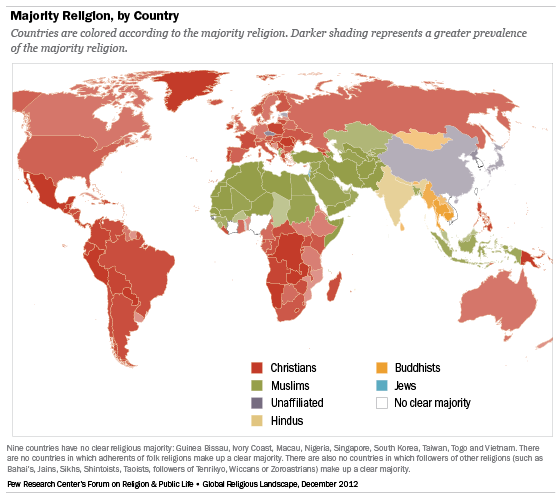

If Huntington was sticking to his religion as the "most important" indicator of Culture, then perhaps he used that as the basis for his map? This map of major world religions from @pewresearch actually looks fairly similar to Huntington's map.

But "fairly similar" is not the same as "the same". In particular, notice that, according to the Pew map, 🇺🇸 & 🇲🇽 fall into the same religion category. But if you go back to Huntington's map, they're not (USA is "Western" & Mexico is "Latin America"). Hmmm...why might that be?

Well, we don't have to look too far to figure that out. Huntington tells us in his next book, which has a full-on anti-Latin American (specifically Mexico) immigration diatribe.

amazon.com/Who-Are-We-Cha…

amazon.com/Who-Are-We-Cha…

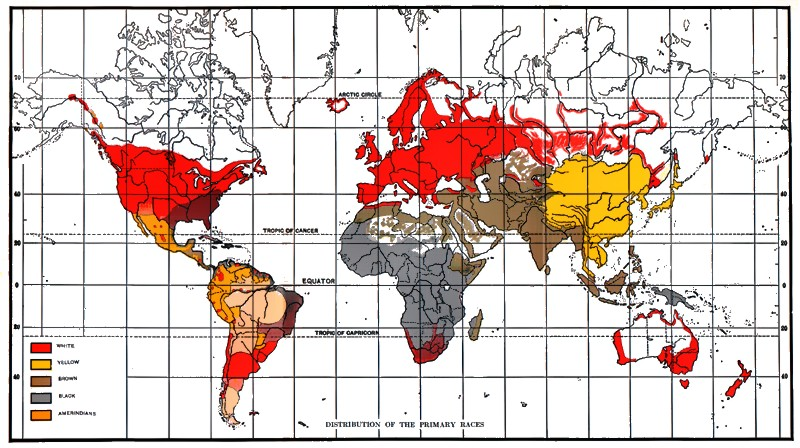

This provides a whole different perspective on Huntington's map. It looks a lot like the "global races" map produced by Lothrop Stoddard in the 1920s.

So the racism underpinning Huntington's claims is text, not just subtext.

THAT is only partially why the work has done damage. After all, racist work that's not supported by evidence should be discarded, right?

That didn't happen.

THAT is only partially why the work has done damage. After all, racist work that's not supported by evidence should be discarded, right?

That didn't happen.

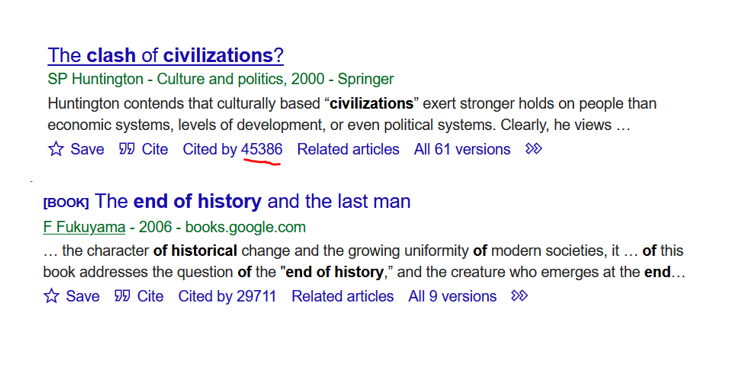

The work is WIDELY cited, perhaps the most cited piece of IR scholarship, ever (just compare it to Fukuyama's "End of History". Not even close).

Most importantly, the idea of a "Clash of Civilizations" became embedded in media (and government) discourse about US foreign policy.

These range from...

These range from...

...how the US invasion of Afghanistan was framed...

washingtonexaminer.com/weekly-standar…

washingtonexaminer.com/weekly-standar…

...to discussions of ISIS...

csis.org/analysis/clash…

csis.org/analysis/clash…

...to views about the US-China rivalry...

washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/…

washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/…

...to the current War in Ukraine.

nytimes.com/2022/03/30/opi…

nytimes.com/2022/03/30/opi…

While we've debated whether Clash should even be taught to IR students...

networks.h-net.org/node/28443/dis…

networks.h-net.org/node/28443/dis…

...my view is that the idea is already out there, in a big way.

IR scholars can't influence `Clash's' broad prominence, but IR scholars can educate about why it's bad scholarship.

IR scholars can't influence `Clash's' broad prominence, but IR scholars can educate about why it's bad scholarship.

In short, Huntington's "Clash of Civilization" has done damage to IR scholarship because it's a racist & empirically groundless theory that is nevertheless quite popular.

[END]

[END]

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh