#OTD #Onthisday 3 February 3, 1813, King Frederick William III of Prussia issued a call to arms to all the people between the age 17 and 24.

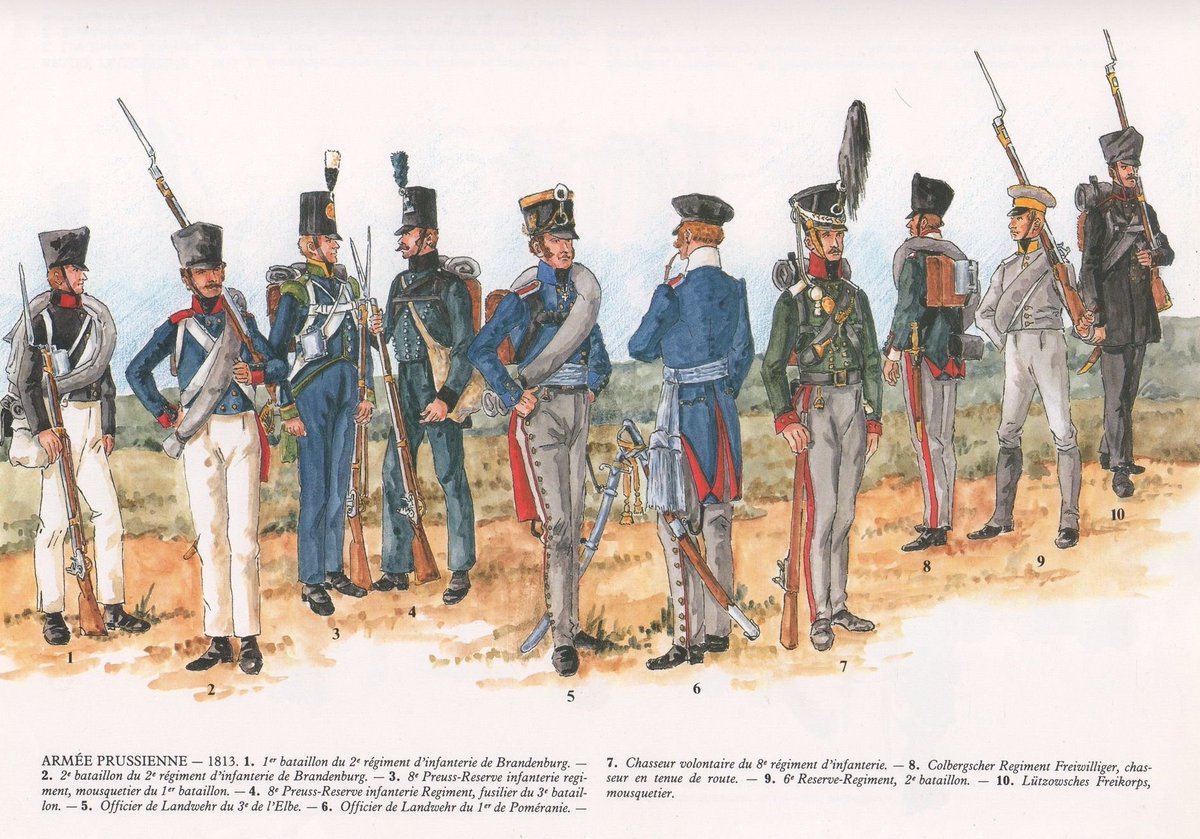

Ostensibly designed to fulfill Napoleon's demand for a Prussian corps, the new conscripts served as the precursor to Landwehr.

Ostensibly designed to fulfill Napoleon's demand for a Prussian corps, the new conscripts served as the precursor to Landwehr.

Signed by Hardenberg, the royal decree from Breslau stated:

“The dangerous situation in which the State now stood demanded a speedy augmentation of the existing force, while the finances did not admit of any great expenditure;

“The dangerous situation in which the State now stood demanded a speedy augmentation of the existing force, while the finances did not admit of any great expenditure;

that the patriotism and faithful loyalty of the people only needed in its thirst for activity to receive a definite direction to an appropriate object, and they would reinforce the ranks of the old defenders of the country and emulate their valor;

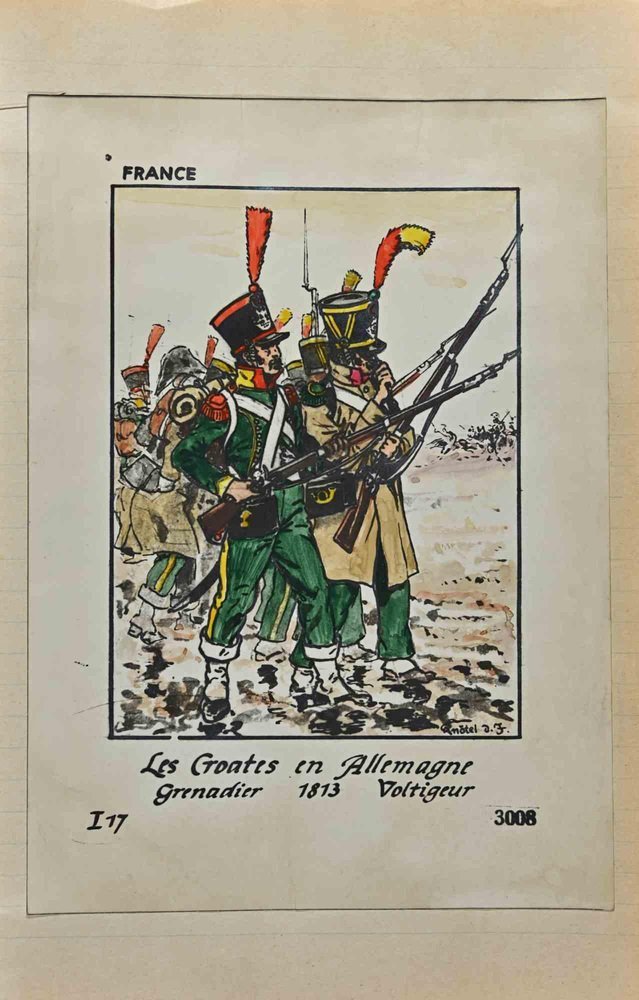

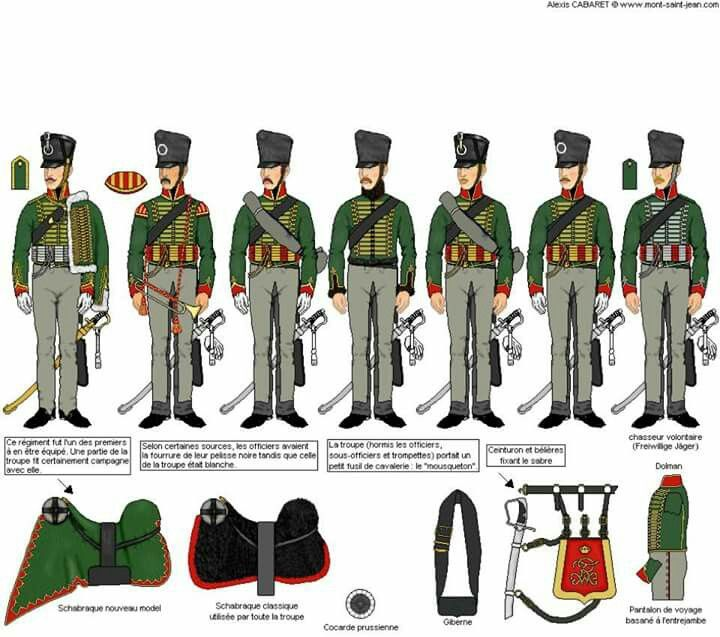

that with this view the King had decreed the formation of companies of Chasseurs to be attached to the battalions of infantry and regiments of horse, especially in order to draw those classes of the population who were exempt…and were rich enough to clothe and mount themselves,

into the military service in a way suitable to their education, and to give an opportunity of distinction to such young men as by their culture and intelligence were able at once without preliminary drill to render good service, and would speedily furnish skillful officers…”

It then stipulated ten points “in order to contribute to the defense of the country, and thus to realize its just expectations.”

They included a code of dress-"a dark green uniform" and, for the mounted units, a choice between personal and regimental saber.

(Seeley, Fain)

They included a code of dress-"a dark green uniform" and, for the mounted units, a choice between personal and regimental saber.

(Seeley, Fain)

Although issued under the pretext of providing the Prussian corps requested by Napoleon, the king’s proclamation caused the local patriots to tremble with zeal.

Finally, what the anti-Napoleon party led by Scharnhorst in 1807 was beginning to take shape.

(Leggiere)

Finally, what the anti-Napoleon party led by Scharnhorst in 1807 was beginning to take shape.

(Leggiere)

The universal conscription, less sparing of the privileged than France’s but offering more humane terms than Russia’s 25-year-contract to the serfs, began to foment a sense of cohesion among those who had deplored the crippled state of their country following successive defeats.

The local patriots immediately grasped the subtext of the long-awaited proclamation.

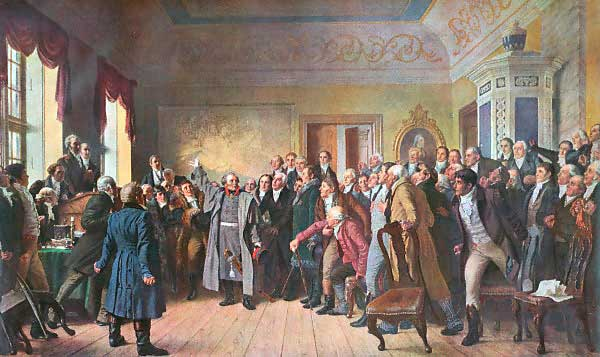

At 8 o'clock in the morning, a professor at the University of Breslau was about to start a lecture on natural philosophy when he heard the clamor outside.

(Poultney Bigelow)

At 8 o'clock in the morning, a professor at the University of Breslau was about to start a lecture on natural philosophy when he heard the clamor outside.

(Poultney Bigelow)

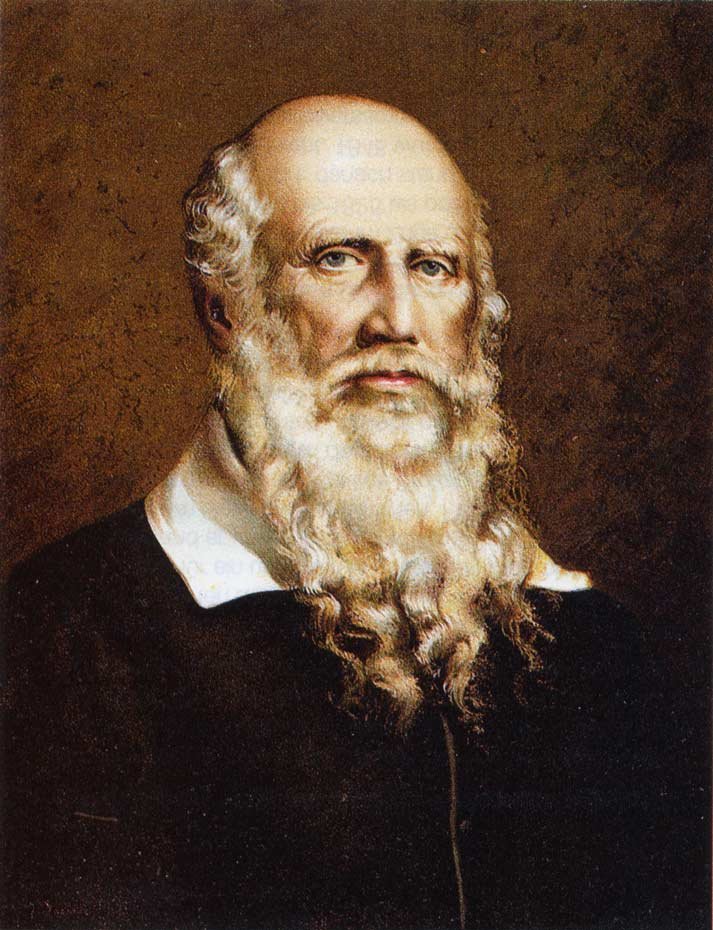

The particular scene was vividly witnessed by 35-year-old Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, 'the Father of Modern Gymnastics':

"On the King's proclamation of February 3, 1813, all the turners capable of bearing arms entered the field."

(Report of the Secretary of the Interior, Jan. 1895)

"On the King's proclamation of February 3, 1813, all the turners capable of bearing arms entered the field."

(Report of the Secretary of the Interior, Jan. 1895)

The professor, although of Scandinavian descent, has longed to see his current home liberated. Moved by most of his students distracted by "the rumbling of artillery trains and the cheers of the volunteers," he announced:

"Gentlemen , I have another lecture set down for eleven o'clock. I shall use that time in addressing you upon a matter of great importance. The King's call for the young men to arm as volunteers has appeared, or will appear to-day . This will be the subject of my address.

Make this purpose of mine public . The other lectures may be ignored to-day. I expect as many hearers as my room will hold."

As soon as he finished his speech, the remaining students "broke out into uncontrollable cheering , and burst from the room to spread the news."

(P.B.)

As soon as he finished his speech, the remaining students "broke out into uncontrollable cheering , and burst from the room to spread the news."

(P.B.)

The prevailing mood was made official by the government in Potsdam, which reported that "Everyone seems to be convinced that the present extraordinary effort...is intended to establish the prosperity and independence of [the fatherland]."

The rest of the narrative showed a marked absence of either France or Napoleon:

"The hope of an early release from the hitherto suffered tribulations revives our courage anew. It is a pleasure to note, with what praiseworthy zeal and public spirit everything is now pursued.."

"The hope of an early release from the hitherto suffered tribulations revives our courage anew. It is a pleasure to note, with what praiseworthy zeal and public spirit everything is now pursued.."

At nine o'clock in the morning, Napoleon had a second interview with Count Bubna, the Austrian ambassador to Paris. He aggressively questioned the underlying motives for Franz I's letter from 23 January, which reiterated his desire for "a stable state of peace."

(Oncken)

(Oncken)

It was a disturbingly ambiguous reply to his condescending request on 7 January, that Austria grant a free passage to the French troops in the next campaign.

According to a briefing by Bubna, Napoleon was visibly agitated by the suddenly dovish turn of father-in-law.

According to a briefing by Bubna, Napoleon was visibly agitated by the suddenly dovish turn of father-in-law.

He nearly interrogated the envoy,

"What is the Emperor of Austria write to me?"

The latter, however, was under a strict instruction from Metternich to "never depart from the principle of not granting a passage of troops" which would entangle Austria into a war.

(25 Jan)

"What is the Emperor of Austria write to me?"

The latter, however, was under a strict instruction from Metternich to "never depart from the principle of not granting a passage of troops" which would entangle Austria into a war.

(25 Jan)

Bubna carefully explained his emperor's letter word by word, that he yearned for nothing but to fulfill "the first need of his people...the surest means of consolidating the order of things in France" and maintaining "the happy connection...between our two Houses."

(23 Jan)

(23 Jan)

Luckily for the ambassador, Napoleon redirected his frustration toward himself. He ordered a secretary to read aloud his letter to Franz I on the 7th, "to see which passages could have caused misinterpretation."

(Bubna, Oncken)

The French Emperor, then, declared:

(Bubna, Oncken)

The French Emperor, then, declared:

"C'est un verbiage, j'aurais pu m'en passer!"

Surprisingly, he admitted that his demands could have been taken as a threat to Austria, and assured Bubna:

"....I have only written this in a moment of heartfelt joy, out of my utter devotion to him."

(Ibid)

Surprisingly, he admitted that his demands could have been taken as a threat to Austria, and assured Bubna:

"....I have only written this in a moment of heartfelt joy, out of my utter devotion to him."

(Ibid)

Thus ended another fruitless interview, which Bubna would let Metternich know of.

Meanwhile, Eugene sent another letter to Schwarzenberg. Out of desperation, the viceroy pleaded him to return to Posen, or at least Kalisz; beyond there would be a point of no return.

(Charras)

Meanwhile, Eugene sent another letter to Schwarzenberg. Out of desperation, the viceroy pleaded him to return to Posen, or at least Kalisz; beyond there would be a point of no return.

(Charras)

To Napoleon, Eugene reported the result of Berthier's intelligence, conducted a few days before his departure.

The Chief-of-Staff, notwithstanding his illness, had dispatched an officer to the Russian outposts to confirm the following:

The Chief-of-Staff, notwithstanding his illness, had dispatched an officer to the Russian outposts to confirm the following:

"1. To send money to a staff officer taken prisoner

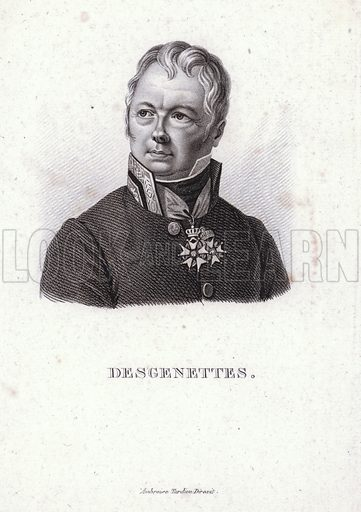

2. To send him news of the Dr. Desgenettes [who has been performing the same job for the Russians]

3. Finally, to gather some certain data on the location of the enemy headquarters."

(Eugene, Memoires; 3 February)

2. To send him news of the Dr. Desgenettes [who has been performing the same job for the Russians]

3. Finally, to gather some certain data on the location of the enemy headquarters."

(Eugene, Memoires; 3 February)

Eugene's envoy had succeeded on the third; he located, as of 31 January, Voronzov's division at Bromberg and Pordon, Chichagov at Strasbourg, and another division of Wittgenstein at Galopp, and Kutuzov's general headquarter in Wittenberg.

(More/Replies)

(More/Replies)

Eugene added that Wittgenstein had only deployed 1,500 Cossacks to attack Danzig, while it was still mostly quiet in Thorn.

It is evident that the report was not only belated but also underestimated the strength of the Russians, who were slowly besieging the two garrisons.

It is evident that the report was not only belated but also underestimated the strength of the Russians, who were slowly besieging the two garrisons.

The remainder of the Potsdam Government's report suggests that even those outside the war zone were becoming seized with fear of the incoming Russians:

"In Tangermünde, a French officer, who thought the Cossacks were already nearby, wanted to set fire to the magazine there..."

"In Tangermünde, a French officer, who thought the Cossacks were already nearby, wanted to set fire to the magazine there..."

His comrades were about to approve of his decision, until "a non-commissioned officer with 4 men of the Citizen Militia" came to arrest him, armed with "most fearless determination." (Oncken)

It would not be long before the Cossacks cease to be the only threat nearby.

It would not be long before the Cossacks cease to be the only threat nearby.

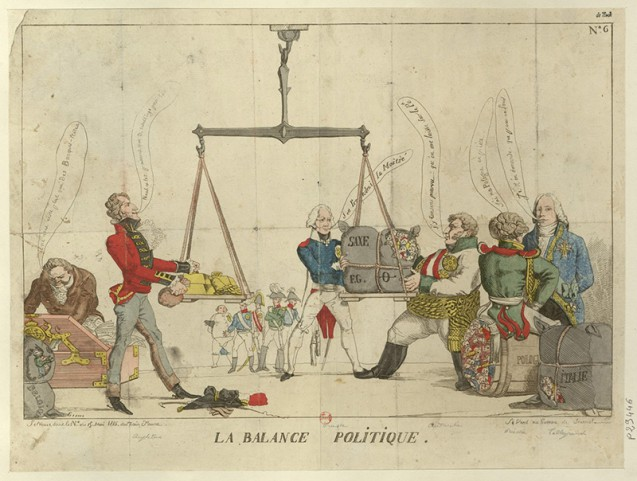

That evening, Colonel Knesebeck returned from Vienna, carrying confidential dispatches from Metternich and Zichy on the 30th. These stated, as Hardenberg summarized in his diary, that "the unification of the Prussian and Russian forces would put a considerable counterweight to

the balance [of power] in favor of a peace," and that Austria shall adhere to its original plan of refraining from influencing any other state.

At the same time, they emphasized that Prussia's alignment with Russia would not alter "the inseparable harmony of the two cabinets."

At the same time, they emphasized that Prussia's alignment with Russia would not alter "the inseparable harmony of the two cabinets."

Combined with the mass conscription, the gradual settling of potential differences with Austria paved the way for Prussia's resistance against Napoleon.

Knesebeck's next destination would be Tsar Alexander's headquarter, where he would verify Natzmer's words.

Knesebeck's next destination would be Tsar Alexander's headquarter, where he would verify Natzmer's words.

Just on the day the formerly hesitant king announced the first step to restoring his devastated country, Ambassador Thorton wrote to Castlereagh that "The example of Prussia may spread like wildfire through the whole of Germany."

(Thorton to Castlereagh, 3 February 1813)

(Thorton to Castlereagh, 3 February 1813)

Attaching a copy of Tsar Alexander's letter to Bernadotte from 25 December, Thorton ascertained Sweden's participation in the next campaign:

"Your lordship will see, from this letter of the Emperor, that the Russian auxiliary troops will be embarked from the ports of Prussia,

"Your lordship will see, from this letter of the Emperor, that the Russian auxiliary troops will be embarked from the ports of Prussia,

where shipping in abundance may be found for their reception and transport, by which means a space of perhaps two months' time will be anticipated, and the expedition may be prepared to act in April , instead of the end of May, or June,

as would have been the case if the embarkation had been made from Finland , or from the opposite coast of the Gulf, Reval, or even Riga.

In the meantime, the rapid progress of the Russian arms may diminish even the length of this voyage,

In the meantime, the rapid progress of the Russian arms may diminish even the length of this voyage,

and they may be embarked still nearer to the future scene of action in the North of Germany."

As for the rumor of "reported attempt to carry off the King of Prussia," he explained that it had been "intended to place him "as much as possible in the midst of his troops,"

As for the rumor of "reported attempt to carry off the King of Prussia," he explained that it had been "intended to place him "as much as possible in the midst of his troops,"

for "it was the intention of Buonaparte, in case of a successful campaign against Russia, to possess himself of the whole royal family of Prussia, and to extend the French empire to the Oder."

In this manner, the architecture envisaged by Metternich was coming into shape.

In this manner, the architecture envisaged by Metternich was coming into shape.

-The End-

@threadreaderapp Unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh