UNIT ECONOMICS

"Unit economics" is an important tool in the tool box for the buy-side analyst that, surprisingly, is not discussed often by the sell-side outside of businesses that explicitly report enough data to calculate LTV (life-time value) and

"Unit economics" is an important tool in the tool box for the buy-side analyst that, surprisingly, is not discussed often by the sell-side outside of businesses that explicitly report enough data to calculate LTV (life-time value) and

CAC (customer acquisition cost), two important, but incomplete metrics in understanding the totality of unit level profitability.

Honestly, when I joined a hedge fund and heard other analysts talking about unit economics, I was lost. I hit the google machine and looked through

Honestly, when I joined a hedge fund and heard other analysts talking about unit economics, I was lost. I hit the google machine and looked through

my finance textbooks, but came up empty. I eventually had to ask a senior analyst, sheepishly, to walk me through the concept. So I'll do my best to pay that kindness forward here.

WHAT ARE UNIT ECONOMICS

"Unit economics" is a concept that looks at the key fundamental metrics

WHAT ARE UNIT ECONOMICS

"Unit economics" is a concept that looks at the key fundamental metrics

of a business expressed on a per unit level. Specifically, we are looking at unit level operating profitability and FCF generation.

The mindset: if a business works on a unit level, it can scale and create a strong aggregate profit.

If it doesn't ("broken unit economics"),

The mindset: if a business works on a unit level, it can scale and create a strong aggregate profit.

If it doesn't ("broken unit economics"),

scaling those unit economics is unwise. Seems silly to say that, right? You'd be SHOCKED how many large, scaled businesses, in their current state, have unit economics that look like the proverbial "selling dollar bills for 80c".

Particularly in the "blitzscaling" VC-backed,

Particularly in the "blitzscaling" VC-backed,

fed-induced liquidity bubble of the last decade, this has become incredibly common. The playbook for many businesses: get to volume scale and squeeze out the competition with subsidized (i.e. weak) unit economics, then hope to improve that unit level profitability in the future.

Some will, many won't.

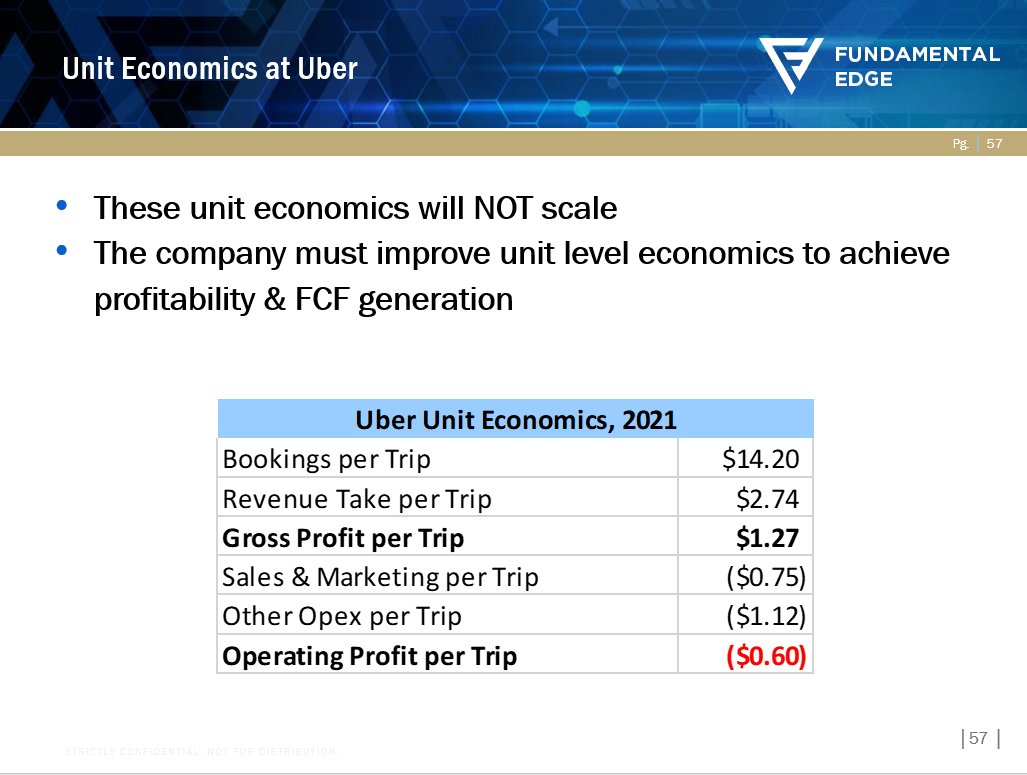

Do you know that, on an aggregate level, Uber loses 60c on every ride?

Do you know that NFLX, despite massive scale, only makes 11c per member per month?

And that TSLA was losing money on every car as recently as 2019?

Do you know that, on an aggregate level, Uber loses 60c on every ride?

Do you know that NFLX, despite massive scale, only makes 11c per member per month?

And that TSLA was losing money on every car as recently as 2019?

The challenge. Stocks are priced on collective future expectations of decades of FCFs. In buying some of these stocks, whether you know it or now, you are making a bet on the future trajectory of unit economics.

So as an analyst, understanding the current strength of unit economics, and critically which levers can be pulled to influence the forward trajectory, is very important.

Let me walk you through a hypothetical.

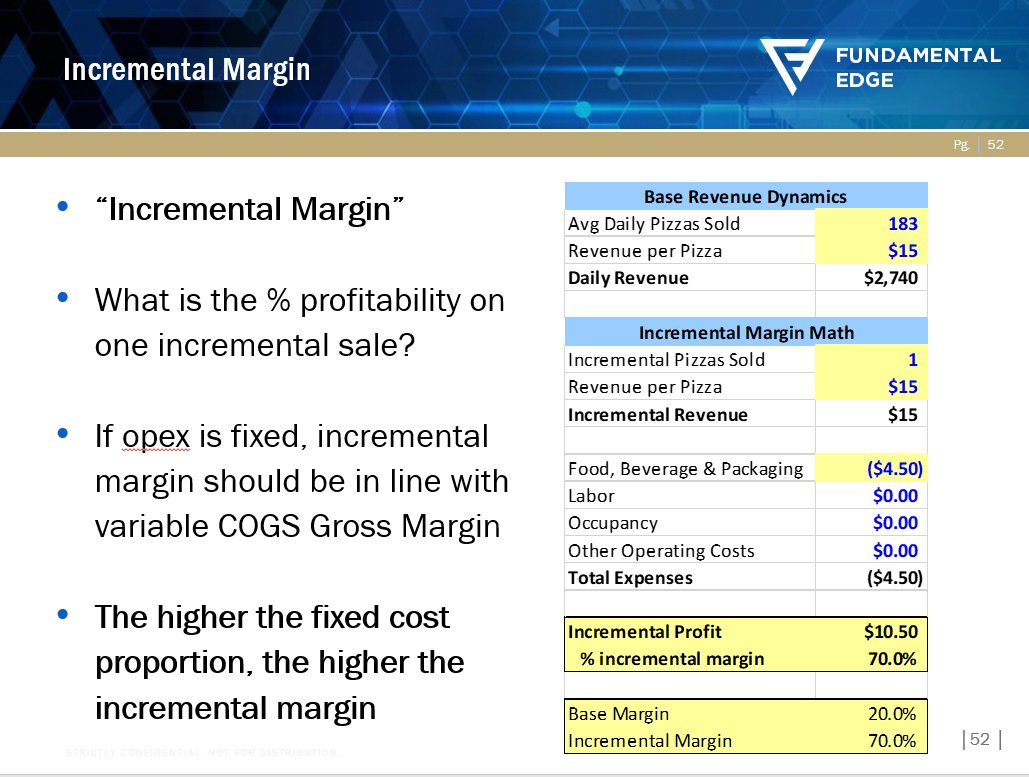

If I am looking at a Pizza shop, I will first look at the cost

Let me walk you through a hypothetical.

If I am looking at a Pizza shop, I will first look at the cost

breakdown of the business. What are the key line items on the P&L? I like to then express revenue and the cost items on a per unit basis. My first check - what is aggregate unit level profitability in current state? Is this a "unit economics improvement story" or are we just

maintaining and scaling strong unit economics that are currently present in the P&L. This distinction is important.

I will then try to think through, if I sell one incremental unit, what happens? For a pizza, I have the $4.50 food/packaging cost, but the other costs are either

I will then try to think through, if I sell one incremental unit, what happens? For a pizza, I have the $4.50 food/packaging cost, but the other costs are either

fixed or semi-fixed in direct relation to volume, with with 70% GM and 70% "incremental margin) I have strong unit level economics here of $10.50 GP per pizza.

If the business is already doing strong levels of profitability in aggregate and on a per unit basis, your job in

If the business is already doing strong levels of profitability in aggregate and on a per unit basis, your job in

analyzing unit economics is easy (and you may move on to using other analyst tools to diligence the stock).

But it's not always so straight forward.

A pizza biz may have strong underlying unit economics, but simply be early in the life cycle of the business and not at volume

But it's not always so straight forward.

A pizza biz may have strong underlying unit economics, but simply be early in the life cycle of the business and not at volume

breakeven. This requires more teasing out of underlying unit economics and determining what % of the opex base can be leveraged as volumes grow. A trickier proposition, for sure (with a higher risk profile...but the bet that unit economics are good/will improve when the market

is skeptical can be explosive for stock prices...see TSLA in a moment).

The risk here is that our pizza shop in question raised a huge VC round and VC's want revenue growth! (I like to pick on VC's. It's fun, and pretty easy). So let's grow! I'll sell my pizzas for $5

The risk here is that our pizza shop in question raised a huge VC round and VC's want revenue growth! (I like to pick on VC's. It's fun, and pretty easy). So let's grow! I'll sell my pizzas for $5

with $5 food COGS and this is such an excellent value proposition that customers will love it!

This is why you could get $15 Ubers and $1,000/month WeWork offices over the last decade. These are the equivalent of $5 pizzas.

But this is an incredibly risky bet. You are betting

This is why you could get $15 Ubers and $1,000/month WeWork offices over the last decade. These are the equivalent of $5 pizzas.

But this is an incredibly risky bet. You are betting

as the business that you can hook your customer then normalize pricing or reduce sales & marketing.

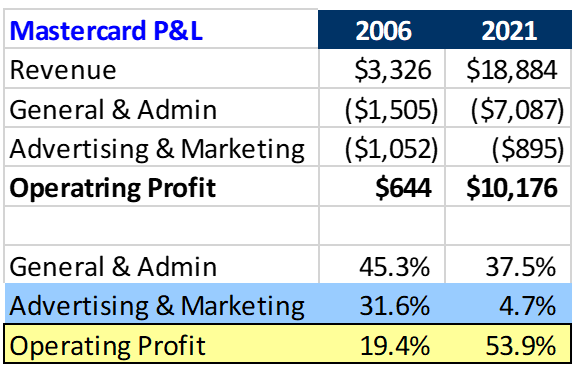

Directionally, businesses are able to do this. Mastercard in 2006 spent $1bn on marketing with 19% margins. By 2021 then spent only $900m, despite revenues up 5x. Margins (and the

Directionally, businesses are able to do this. Mastercard in 2006 spent $1bn on marketing with 19% margins. By 2021 then spent only $900m, despite revenues up 5x. Margins (and the

stock) soared! The majority of businesses will invest in the early stages of their life cycle in attempt to normalize profitability at scale. This is natural. But many companies have done this to an extreme.

UNIT ECONOMICS & UBER

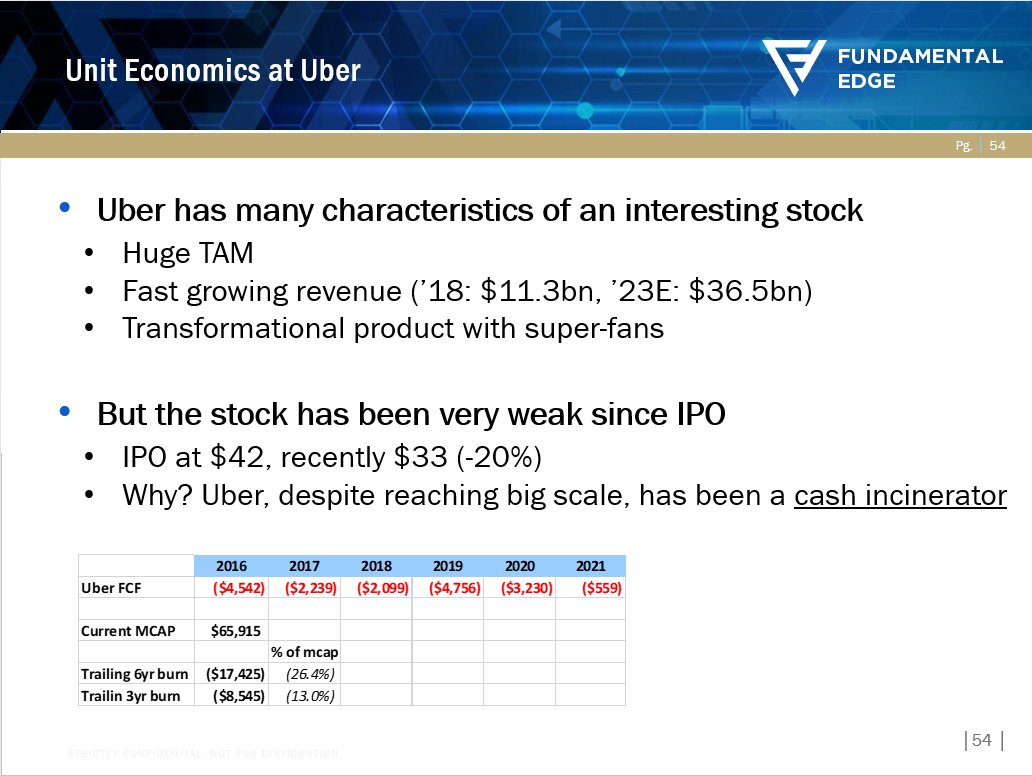

Uber has many characteristics of an interesting stock: huge TAM, fast growing revenue, transformational product with a great value proposition.

But the business has been a cash incinerator and the stock has been a dog. Why?

Uber has many characteristics of an interesting stock: huge TAM, fast growing revenue, transformational product with a great value proposition.

But the business has been a cash incinerator and the stock has been a dog. Why?

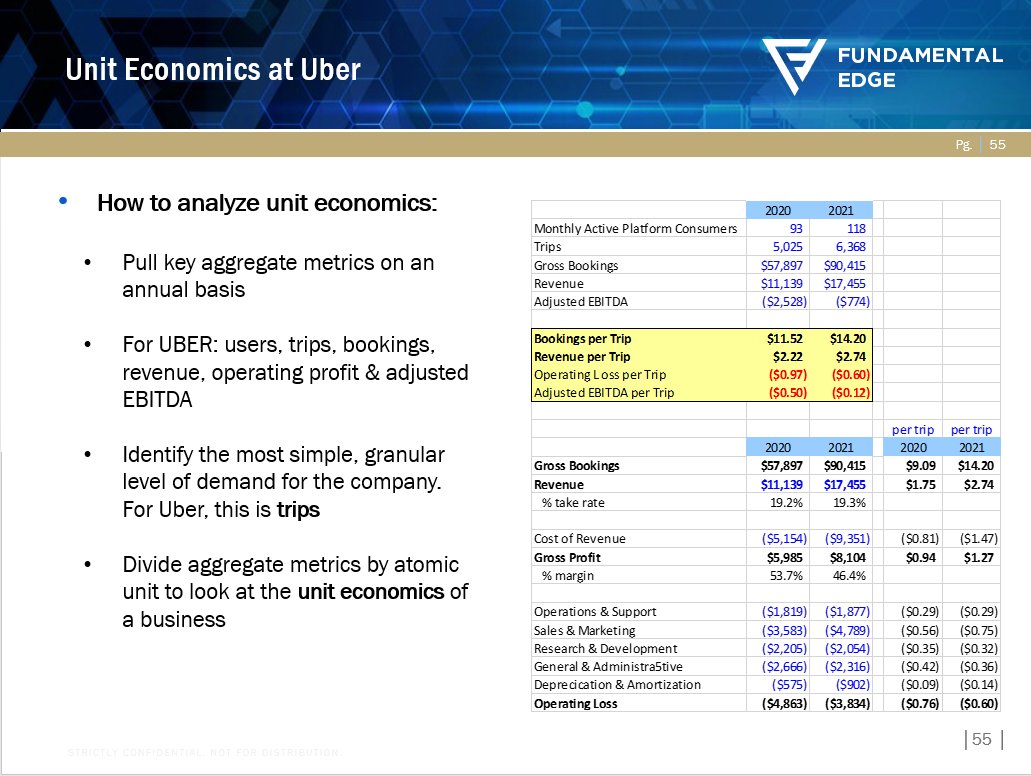

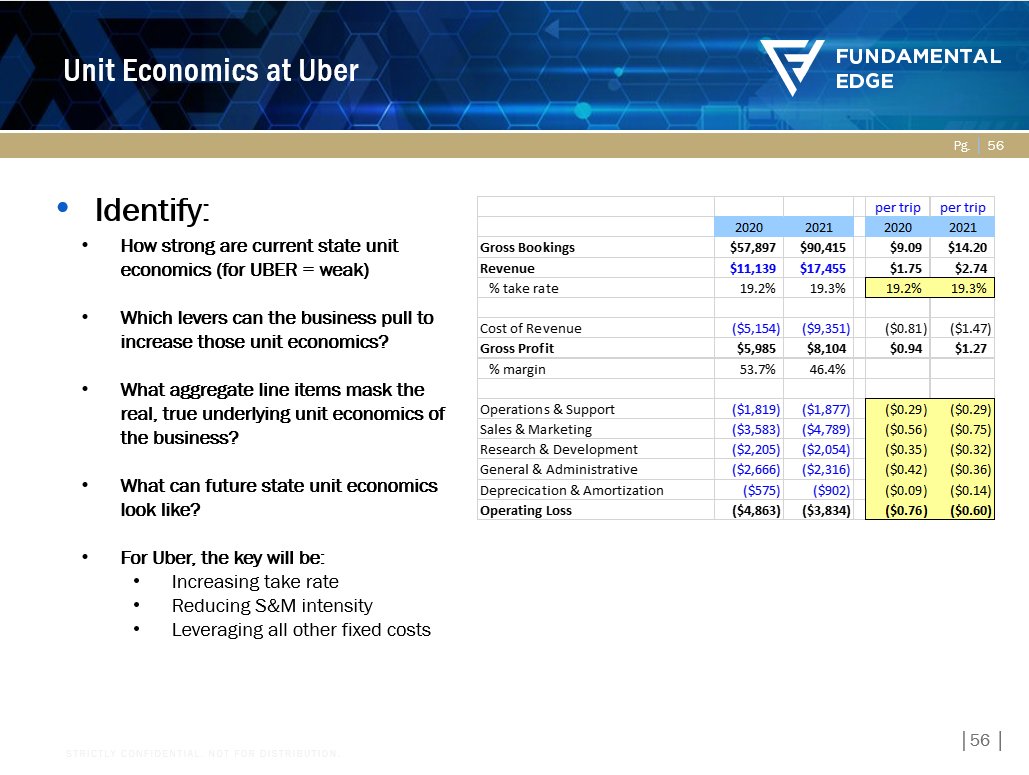

Let's analyze to unit economics to see. I will go to the 10-K and pull all of the aggregate metrics into a table to look at aggregate unit level fundamentals.

What is see is not pretty. Despite gross bookings of $14.20 per trip, Uber keeps only $2.74 (19% take rate), makes $1.27 of GP/trip and loses 60c on every trip, in aggregate.

Should I stop there and chalk this up to Uber having a "broken" business model with broken unit economics. Not necessarily, as the company is working hard to improve these economics.

Ultimately, what will matter is not where the business has been, but where it is going. At this stage, I like to think through ever line item and see what a possible future looks like.

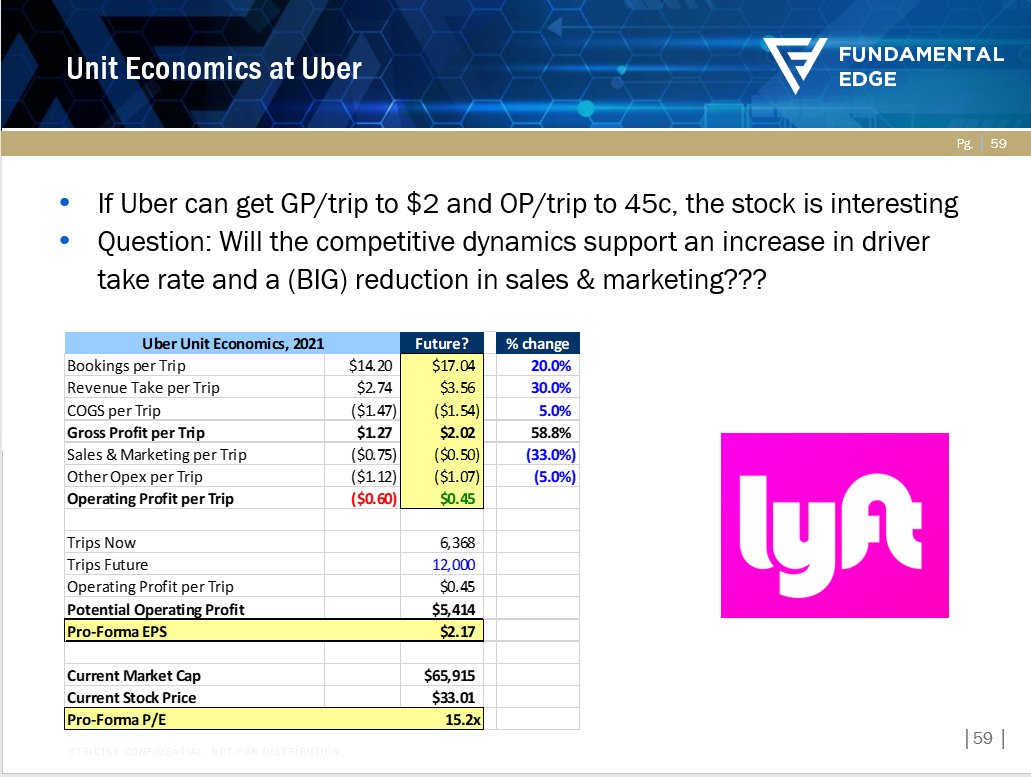

Can Uber go from losing 60c to making 45c ever ride? Growing rides, Uber would be making

Can Uber go from losing 60c to making 45c ever ride? Growing rides, Uber would be making

$5bn of OP in that instance (and be an interesting stock). Is this possible with the competitive intensity from LYFT? Who knows. But for me, as the analyst (who candidly knows extremely little about Uber), this exercise is very important in framing the key research questions for

Uber. For the stock to work, some combo of take rate improvement and sales & marketing reduction is key. If the business can't achieve this, the unit economics will not scale.

CONT'D

CONT'D

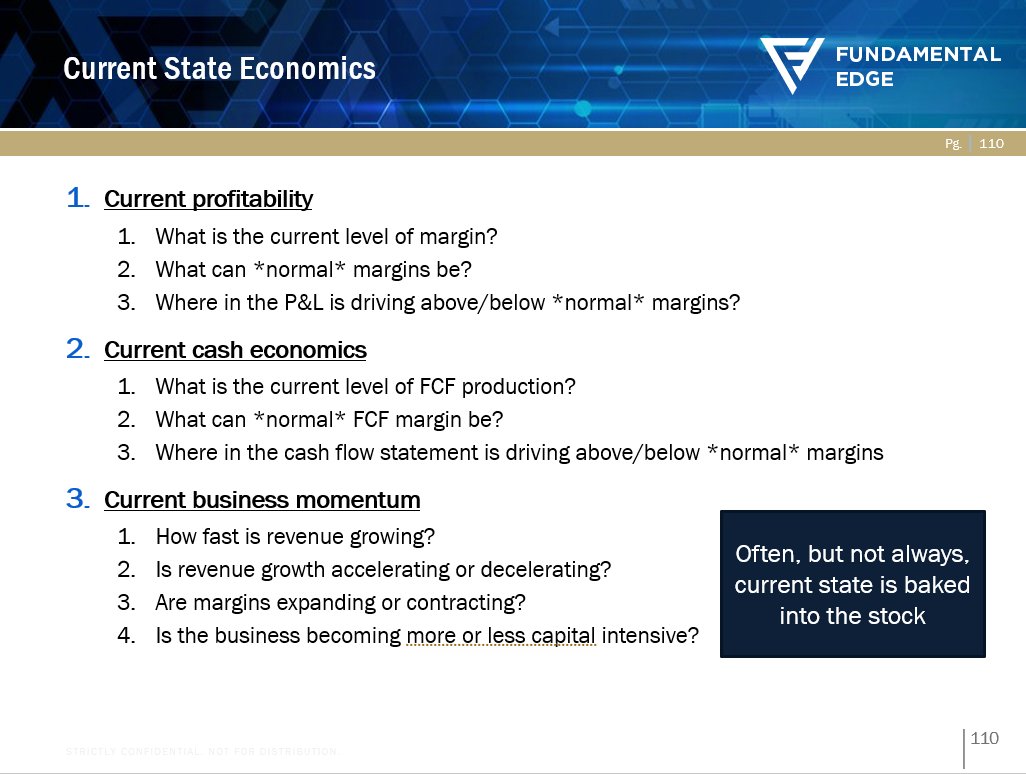

CURRENT STATE, FUTURE STATE

In analyzing unit economics, it's important to remember that the "future state" is what matters. Often, but not always, the current fundamentals of the business are reflected in the stock price (this isn't 1960 and we aren't Warren Buffett reading a

In analyzing unit economics, it's important to remember that the "future state" is what matters. Often, but not always, the current fundamentals of the business are reflected in the stock price (this isn't 1960 and we aren't Warren Buffett reading a

10-K, seeing some key metrics, and buying the stock...the game has changed).

What ultimately matters is a combination of a vision for the future and asymmetry in the odds embedded in the current price.

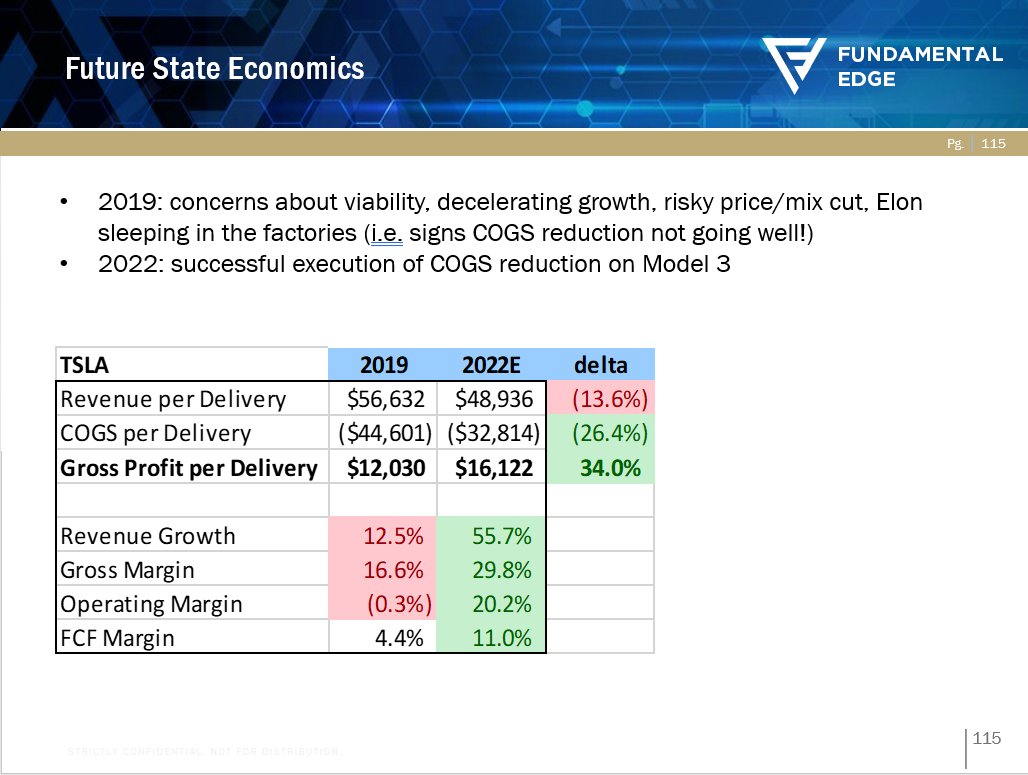

$TSLA, in 2019, had really bad unit economics! They were making, on a GP

What ultimately matters is a combination of a vision for the future and asymmetry in the odds embedded in the current price.

$TSLA, in 2019, had really bad unit economics! They were making, on a GP

basis, $12k per car and spending $12k per car. And Elon decided to cut the price via mix! Risky!

Guess what. It worked. COGS declined 25%+ per car and GP per car expanded from $12k to $16k. Operating Margins expanded.

This isn't a call on TSLA, and where TSLA goes in the

Guess what. It worked. COGS declined 25%+ per car and GP per car expanded from $12k to $16k. Operating Margins expanded.

This isn't a call on TSLA, and where TSLA goes in the

future on a fundamental basis was deterministic to the stock. But TSLA, very simply, was a unit economics improvement story. They hit it, and the stock worked.

HOPE THAT'S HELPFUL!

HOPE THAT'S HELPFUL!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh