A while back I did a thread about The Flock of Ba-Hui, a wonderful little book of Lovecraftian horror translated from Chinese. In this thread I'm going to go into more detail about one of the stories in particular (spoilers ho).

https://twitter.com/XianyangCB/status/1590651355664125952

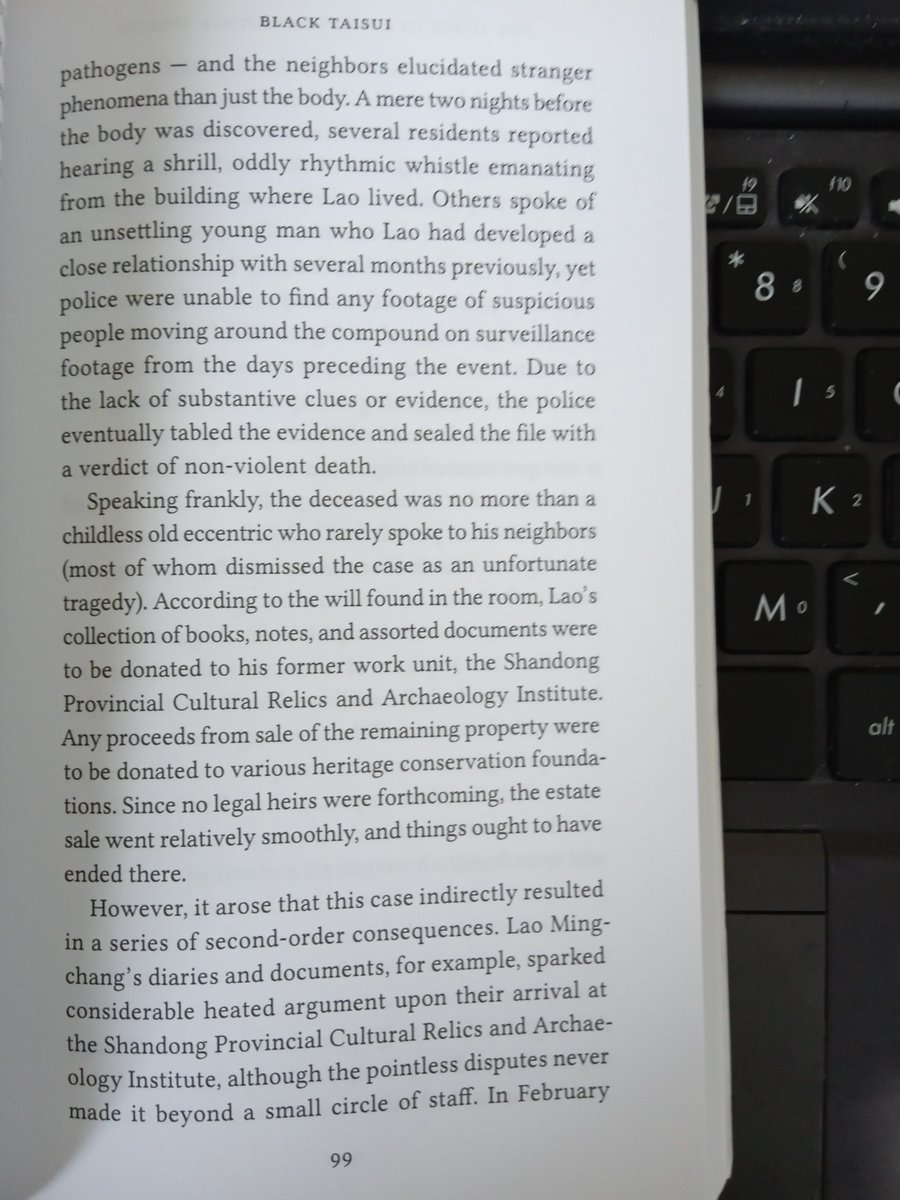

Having duly foreshadowed Lao Mingchang's grisly demise, we learn about the genealogical researches that brought him to such a pass. A keen historian uprooted by the cultural revolution, he had begun investigating his family's past, and particularly an ancestor named Lao Gelin.

The intrepid enquirer, along with a historian colleague named Luo Guangsheng, manages to find the location of his family's former compound and rents the house to further pursue his investigations. All is not well chez Lao, however:

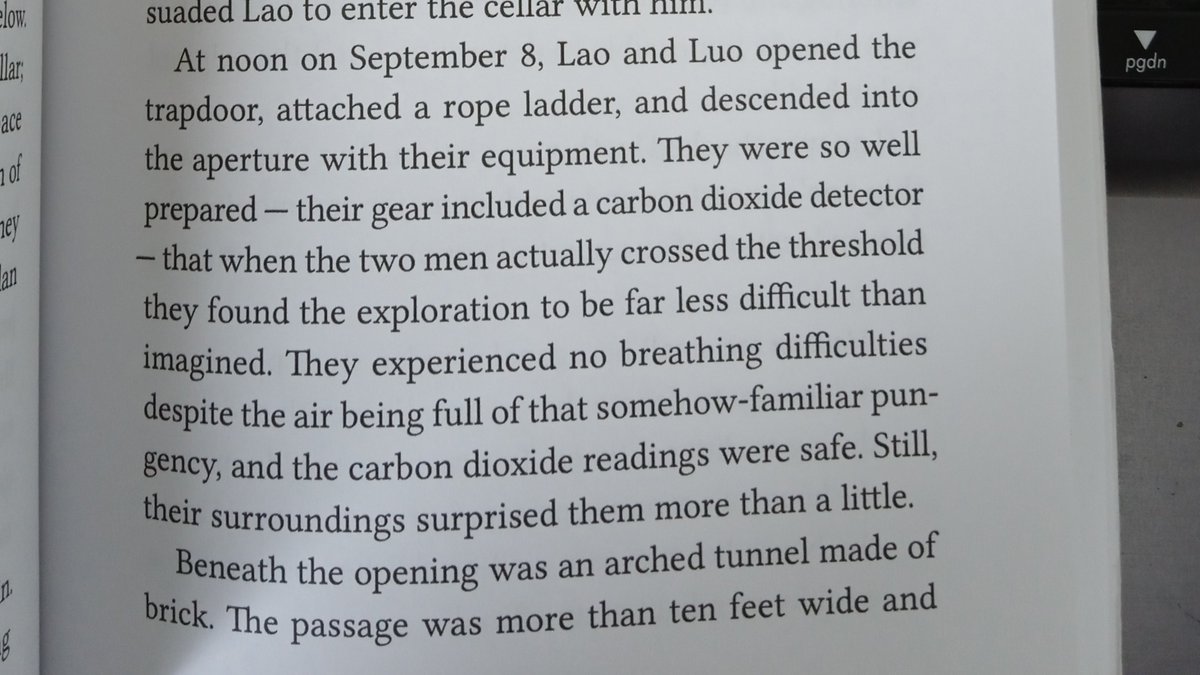

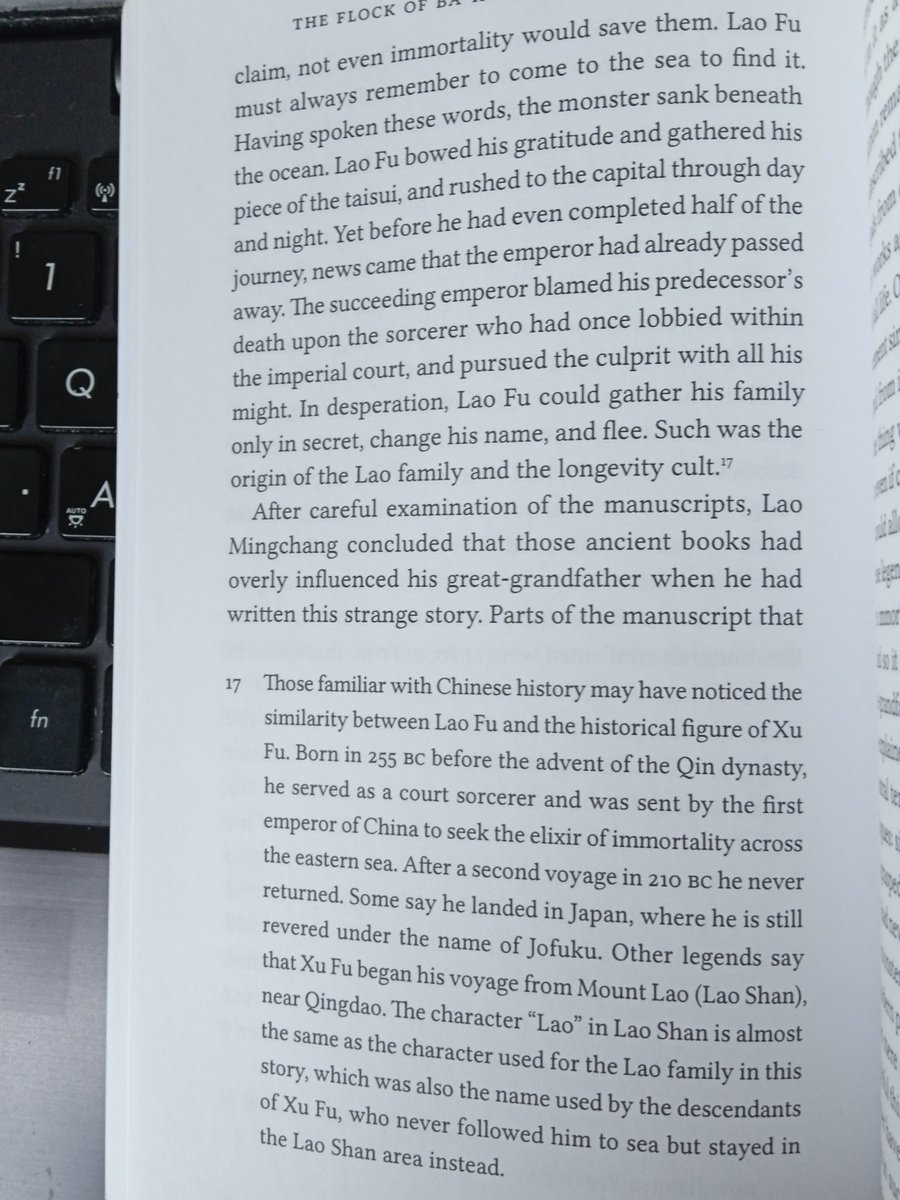

Among the books hidden in the underground temple, Lao Mingchang discovers an account of a conversation with an ancestor from over 2000 years ago, Lao Fu (whom fans of Qin history may recognise), who explains the origins of the family's interest in immortality.

Meanwhile, Luo Guangsheng has apparently succeeded in tracking down some modern members of the School of Longevity, and the Taisui itself...

Unsurprisingly, this does not prove to have a positive effect on his mental health and general well-being:

It's a great story, but it's also a far better description than any I've read in academia of how life after death actually worked in ancient China.

The ancestors were essentially a shoggoth, with the recently deceased plainly visible on the surface as the people they used to be before gradually melting into the composite entity and becoming less and less individuated as the generations passed.

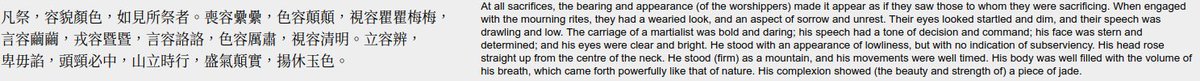

We see it the descriptions of Confucian funeral rites. Immediately after a person's death they were - if anything - more present than they had been in life, both as a corpse and also in the form of the 尸 - a family member appointed as a sort of silent channel or medium.

The texts contain repeated reminders that true sincerity consists in acting as though the dead are physically present, albeit in a different form, however much you may entertain private doubts on this topic (as we know Confucius himself did).

However, in conducting mourning rituals, it was as injurious to allow them to go on too long as to cut them short. Ancestors would receive personal sacrifices for five generations, until the memory of them began to fade, and then sink into the mass of the ancient dead.

The penalties for trying to prolong an ancestor's immortality beyond his allotted span could be quite severe.

https://twitter.com/AdamDSmith1970/status/1537593628104835073

It was possible to exempt oneself from such restrictions by either doing something so noteworthy that the memory of it would justify more durable tribute, or by founding a lineage of one's own (often these were one and the same).

Confucius, whose family is on roughly its 77th generation, is thus still entitled to sacrifices. There may be an awkward moment when the hundredth generation takes over, but even then all is not lost, for there is a 𝘴ₑ𝚌ᵣₑ𝚝 𝚝𝓱ᵢᵣ𝚍 wₐy to prolong one's existence...

The prospect of being subsumed within the family shoggoth may or may not appeal to you personally, depending on your level of individualism and how unpleasant your family is. It is, however, possible to escape it and join another.

This can be done through adoption obviously, but also by joining an intellectual, religious or skills-based lineage. A person known primarily for their work would be associated principally with their master-disciple chain of transmission, rather than family ties.

Thus, for example, we have pretty much no information about Jia Yi's biological family, but we do know that he was a third generation intellectual descendant of Xunzi via Li Si and Wu Tingwei.

But even here the curious phenomenon of borderless personalities coming together to form a composite entity persists. Thus we know a great deal about which of Confucius' disciples taught one another, but not necessarily which ones wrote which texts.

Most of the great Chinese classics were produced in this way, as books by a single author made up of multiple biological entities. In some cases these are followers and fans of whoever wrote the ur-text (this is probably true of the Zhuangzi and the Han Feizi, for example).

In other cases, they are an entirely anonymous group that came together to achieve collective immortality by writing under a name that actually belonged to none of them - the Guanzi is the obvious example.

By remaining present in the minds of one's descendants as an ancestor or by directing their actions through a book, you effectively uploaded your consciousness to the cloud, attaining a form of empirical immortality.

Indeed, looked at from the perspective of the people involved, the ancient fascination with immortality comes to seem quasi-scientific. They knew that bodily immortality was unlikely, but through tested methods one could eke out a few hundred more years than one's physical body.

What remained would not necessarily have the same boundaries as it did in life, but for a people that perceived personalities as composites even in life, possibly this was no big deal...

https://twitter.com/XianyangCB/status/1460081227440930817

Buy the book here, it's great: amazon.com/Flock-Ba-Hui-O…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh