Ik ben blij met dit artikel, maar vind persoonlijk het beeld dat Singor schetst erg problematisch, en gebaseerd op erg tendentieus bewijs. Dit is bovendien een plek waar mijn studie van leestradities wat te zeggen heeft. Een draadje. 🧵

https://twitter.com/BartFunnekotter/status/1626510448043429888

Hij presenteert het conflict tussen Mecca (Mohammed's geboortestad) en Medina (de plek waar Mohammed aan de macht komt) als een proxy-oorlog tussen Byzantijnen en Sassaniden. De Medinesen zouden Byzantijns gezind zijn en de Meccanen Sassanidisch gezind.

Hoe weet hij dat? Hoe kan hij het überhaupt weten? Er is zo weinig geschiedkundig bewijs dat Mecca überhaupt bestond in de pre-Islamitische periode dat veel onderzoekers zich oprecht hebben afgevraagd of het überhaupt wel bestaan heeft!

Dus als we nul bronnen hebben over Mecca voor de Islam, hoe kunnen we dan weten met wie zij politiek gealliëerd zouden zijn?

Dat weten we niet. En kunnen we ook niet weten totdat er meer data beschikbaar komt.

Maar dit idee is natuurlijk wel op IETS gebaseerd.

Dat weten we niet. En kunnen we ook niet weten totdat er meer data beschikbaar komt.

Maar dit idee is natuurlijk wel op IETS gebaseerd.

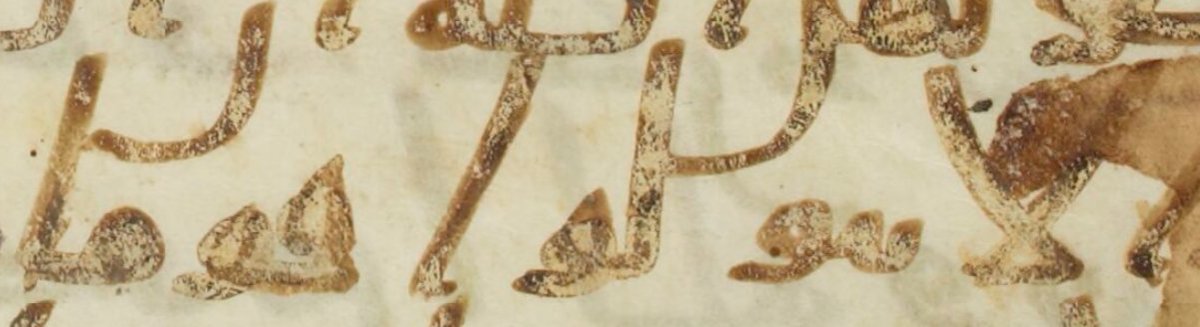

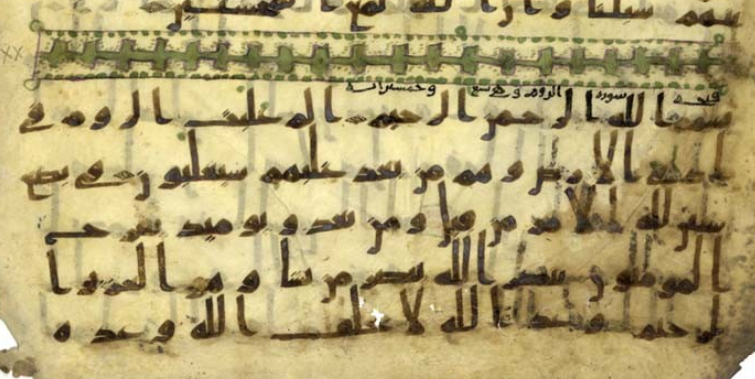

Het is gebaseerd om de exegese van de openingsverzen van de Soera "De Romeinen".

In de standaardlezing van de Koran gaat die als volgt:

Q30:2 De Romeinen zijn overwonnen, (3) in het dichtsbijzijnde land, maar na hun nederlaag zullen zij overwinnen.

In de standaardlezing van de Koran gaat die als volgt:

Q30:2 De Romeinen zijn overwonnen, (3) in het dichtsbijzijnde land, maar na hun nederlaag zullen zij overwinnen.

De Koran lijkt sympathie te hebben met de Romeinen (= Byzantijnse rijk), en doet zelfs een voorspelling (een van de weinige expliciete voorspellingen in de Koran): De Romeinen zullen overwinnen!

Een vreemde vers. Waarom schaart de Koran zich achter de Romeinen?

Een vreemde vers. Waarom schaart de Koran zich achter de Romeinen?

Dat vonden de latere moslimexegeten ook. Die vormden er vervolgens een uitgebreid verhaal omheen om het te verklaren. Maar let wel: deze exegeten schreven honderden jaren NA de compositie van deze verzen. Er is geen reden om aan te nemen dat hun interpretatie klopt.

De exegeten redeneerden: De Byzantijnen waren Christenen, dus ze geloovden in ieder geval in één God! Monotheïsten net zoals Mohammed en zijn volgers. De Sassanieden daarintegen waren polytheïsten net zoals die zo gehaatte polytheïsten in de Koran.

Dus de Koran kiest voor team monotheïsme tegen team polytheïsme.

En als je de vers zo begrijpt, dan krijg je nog een mooie bijvangst: een mirakel!

Want na dat deze verse geöpenbaard zou zijn hebben de Byzantijnen een belangrijke slag gewonnen van de Sasanieden.

En als je de vers zo begrijpt, dan krijg je nog een mooie bijvangst: een mirakel!

Want na dat deze verse geöpenbaard zou zijn hebben de Byzantijnen een belangrijke slag gewonnen van de Sasanieden.

Zo doen we natuurlijk geen geschiedenis. Teksten die succesvol de toekomstvoorspellen doen dat omdat: 1. de tekst is opgeschreven na de gebeurtenissen van de (correcte) voorspelling,

2. De tekst zo is geïnterpreteerd ZODAT je een correcte voorspelling krijgt.

2. De tekst zo is geïnterpreteerd ZODAT je een correcte voorspelling krijgt.

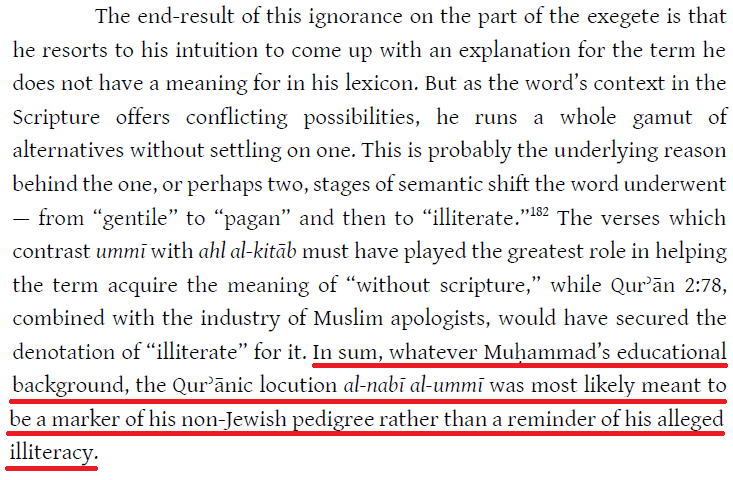

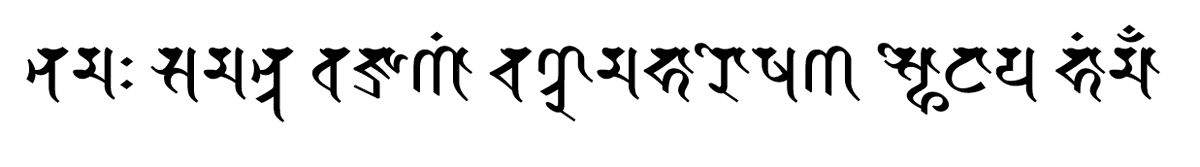

Hier hebben we vrijwel zeker met de tweede optie te maken. En wat blijkt: dit is niet de enige lezing van dit vers. Vanwege het Arabische schrift dat geen korte klinkers kende kuunnen deze twee versen in tegenovergestelde betekenis worden begrepen.

Eerst is er de kanonieke lezing:

ġulibat-i r-rūmu ... sa-yaġlibūna "De Romeinen zijn overwonnen ... en ze zullen overwinnen!"

Of we lezen het in de niet-kanonieke lezing:

ġalabat-i r-rūmu ... sa-yuġlabūna "De Romeinen hebben gewonnen ... en ze zullen overwonnen worden!"

ġulibat-i r-rūmu ... sa-yaġlibūna "De Romeinen zijn overwonnen ... en ze zullen overwinnen!"

Of we lezen het in de niet-kanonieke lezing:

ġalabat-i r-rūmu ... sa-yuġlabūna "De Romeinen hebben gewonnen ... en ze zullen overwonnen worden!"

Die lezing is niet de lezing die de meerderheid aanhield, en wordt niet gekanoniseerd drie eeuwen na Mohammed. Maar we kunnen natuurlijk niet zomaar de orthodoxie van drie eeuwen later terugprojecteren op de vroege Islam, zeker niet als het deel is van een mirakelverhaal!

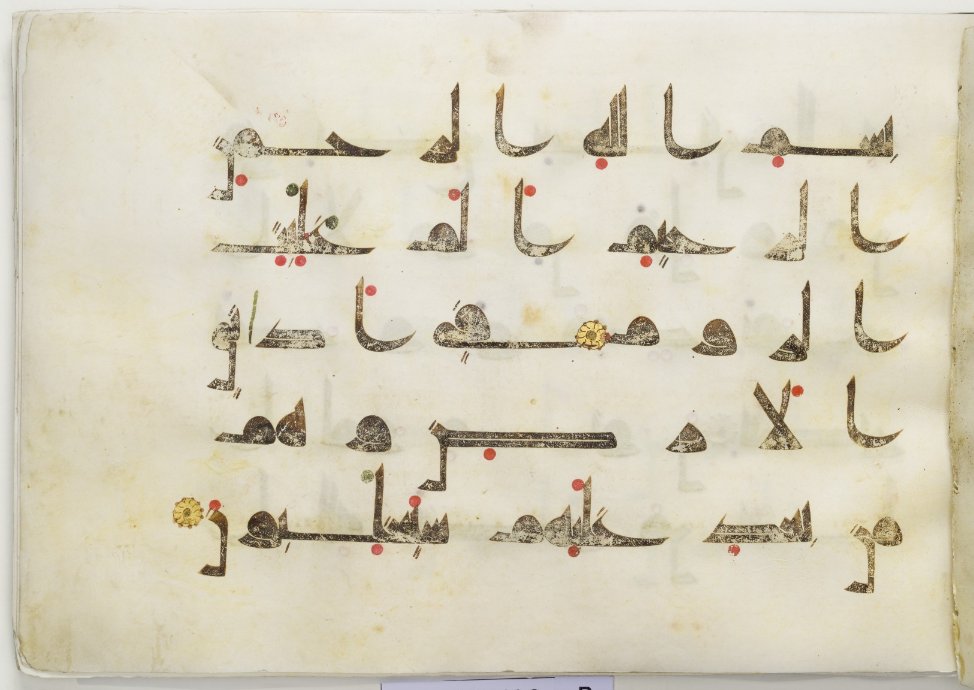

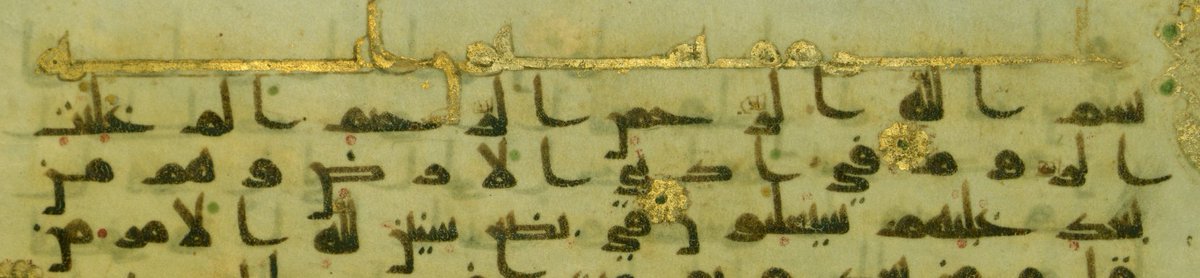

Wanneer Koranmanuscripten klinkers beginnen te schrijven in de loop van de tweede islamitische eeuw, wordt deze alternatieve lezing die het hele verhaal over de kop gooit nog vaak toegevoegd aan manuscripten (hoewel altijd als een secundaire lezing met groene of gele inkt).

Wat ook de oorspronkelijke lezing is van deze vers geweest zal zijn, en waar deze oorspronkelijke lezing precies naar gerefereerd zou hebben kan over gedebatteerd worden. En dat wordt gelukkig ook nog eindeloos gedaan, zonder een duidelijke oplossing.

Maar wat níét kan is de sociale geschiedenis van Mekka en Medina reconstuëren op de basis van een interpretatie van honderden jaren later die gestoeld is op de aanname dat een profetie ook echt is uitgekomen. Mirakels kunnen niet met de historisch-kritische methode worden bewezen

Wat laatste toevoegingen: De reden waarom men aanneemt dat de Mekkanen geallieerd zouden zijn met de Sasanieden is dan ook omdat de traditie aanneemt dat de Mekkanen polytheisten waren. Maar zoals het artikel laat zien is het zéér de vraag of dat klopt.

Ook moet je je afvragen of Mekkanen die, als ze al polytheïstisch waren daarom echt sympathie zouden hebben met een totaal andere groep polytheïsten.

Zouden Chinese polytheïsten pro-romeins heidendom zijn geweest omdat ze ook een hoop (totaal andere!) goden hadden?

Zouden Chinese polytheïsten pro-romeins heidendom zijn geweest omdat ze ook een hoop (totaal andere!) goden hadden?

Een sympathie vanuit Mohammed's volgers richting de Byzantijnen is nog wel voor te stellen. De Koran ziet expliciet zijn god als dezelfde god als die van de Joden en de Christenen...

Ook moeten we best wat vraagtekens zetten bij Zorostriansme überhaupt als polytheisme zien...

Ook moeten we best wat vraagtekens zetten bij Zorostriansme überhaupt als polytheisme zien...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh