Early (premature) thoughts on the Silicon Valley Bank collapse.

It looks like a classic Diamond-Dybvig bank run, when each customer withdraws their money because they want to get their funds out while there's still money in the vault.

It looks like a classic Diamond-Dybvig bank run, when each customer withdraws their money because they want to get their funds out while there's still money in the vault.

SVB might have been especially vulnerable because its customers were a tight-knit community. Often if you have worries, I might not hear about them. But if you have worries, and you share them with your VC, they then tell me to withdraw, and it cascades.

https://twitter.com/mbdailyshow/status/1634225083940995072

We've sort of solved the problem of bank runs: Deposit insurance means folks don't need to respond to dodgy rumors (you'll get paid!), which stops the cascade. (Insured accounts are getting FDIC checks on Monday)

But few of SVB's funds are FDIC insured.

But few of SVB's funds are FDIC insured.

https://twitter.com/mbdailyshow/status/1634225085903978500

So far there's little evidence of contagion.

@WSJ reporting that credit default swaps on the big banks "have barely budged."

There's plenty of headline-worthy charts of certain stocks dipping (eg regional banks), but not much going on where the money is.

wsj.com/livecoverage/s…

@WSJ reporting that credit default swaps on the big banks "have barely budged."

There's plenty of headline-worthy charts of certain stocks dipping (eg regional banks), but not much going on where the money is.

wsj.com/livecoverage/s…

@WSJ SVB is big enough to matter on its own terms. Indeed, it's the second-biggest bank failure in U.S. history (measured in $; I wonder what that looks like scaled by the size of total deposits instead).

And it plays a key role in the Silicon Valley ecosystem

And it plays a key role in the Silicon Valley ecosystem

https://twitter.com/anothercohen/status/1633966144901066752

@WSJ And just like you can't tweet your way out of trouble, SVB couldn't press release its way out, either.

The problem is that every denial that your bank is in trouble only invites the question: "Is your bank in trouble?"

The problem is that every denial that your bank is in trouble only invites the question: "Is your bank in trouble?"

https://twitter.com/lulumeservey/status/1634232327168557057

@WSJ Lotta folks claiming that SVB was a victim of the Fed's interest rate shock.

Nonsense.

Rate rises weren't that big, and they weren't a shock. The Fed telegraphed every move it made.

SVB's problem is that it made a bet and let its losses ride.

Nonsense.

Rate rises weren't that big, and they weren't a shock. The Fed telegraphed every move it made.

SVB's problem is that it made a bet and let its losses ride.

https://twitter.com/mbdailyshow/status/1634225069563019264

Right now, things likely look grim on Sand Hill Road, there may be flickers of trouble in dark corners of Wall Street, but overall, few problems for Main Street.

That said, these are early thoughts, surely premature, and may well be wrong. Time will tell.

That said, these are early thoughts, surely premature, and may well be wrong. Time will tell.

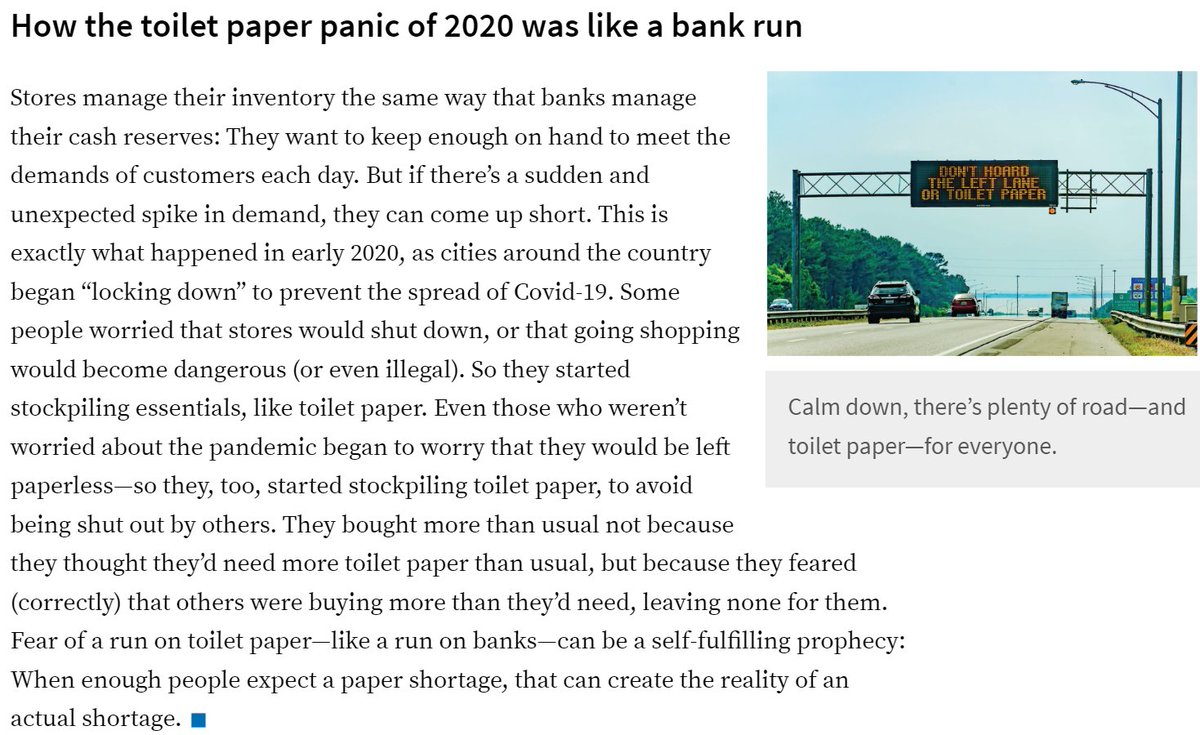

And if you're teaching introductory macro, and want to explain to your students the economics of the Silicon Valley Bank run, then there's a simple way to do it: Talk about a different kind of commercial paper.

[This is from the Stevenson-Wolfers textbook] #TeachEcon

[This is from the Stevenson-Wolfers textbook] #TeachEcon

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh