** What does SVB's failure imply for the Fed hiking cycle?

Bank failures and bailout of large depositors has important implications for financial regulation, moral hazard, and general fairness. Good discussions here and in media.

What about for inflation and monetary policy?

🧵

Bank failures and bailout of large depositors has important implications for financial regulation, moral hazard, and general fairness. Good discussions here and in media.

What about for inflation and monetary policy?

🧵

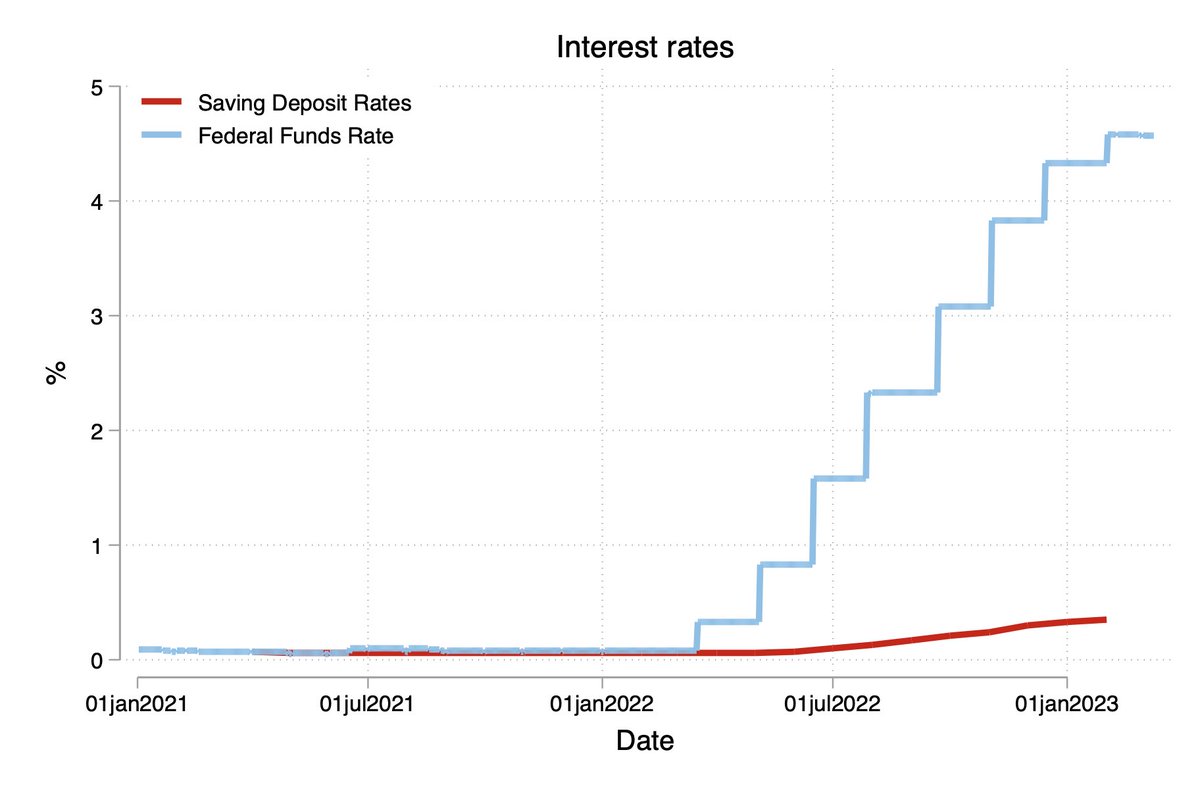

The rate that banks earn on their deposits at the Fed has risen. But the rate that banks pay to their deposits or savings accounts has not. Market power means banks' interest margin is higher, nice profits, the franchise value rises (see work by @AlexiSavov @schnabl_econ @idrechs

Standard monopoly theory: given higher price, banks' customers started buying less. Meaning, deposits moving out of the banks into other investments. Monetary aggregates fall endogenously. This has been going on for a year. Nothing unusual, standard monetarism side of tightening.

In the US, banks bought a lot of MBSs in 2020-21 when deposits were rising. Now, naturally, they have been selling. This puts upwards pressure on mortage rates.

Figure below from a talk by @schnabl_econ at the January AFA:

Figure below from a talk by @schnabl_econ at the January AFA:

This extra tightening of mortgage rates is one of the channels through which inflation is brought down. You see its effects through the construction sector being the one shrinking fast in last year. It is from the monetary policy playbook.

But, if a few (small to medium) banks with depositors that:

(i) are quick to move deposits into higher-yielding savings, and

(ii) are in a "information bubble" so they are very quick to run in herds,

then you can have a run, bank failures, a crash.

amazon.com/Crash-Course-C…

(i) are quick to move deposits into higher-yielding savings, and

(ii) are in a "information bubble" so they are very quick to run in herds,

then you can have a run, bank failures, a crash.

amazon.com/Crash-Course-C…

What does the central bank do, from a strict monetary-policy inflation-control perspective, if it sees a run? It provides liquidity to stop further runs, and halt a too-violent contraction in money aggregates. Fed's weekend action is from the playbook.

amazon.com/21st-Century-M…

amazon.com/21st-Century-M…

What's the next playbook step? If see a very quick sell-off of MBS, and worry about fire sale, then step in and do QE standing ready to buy MBS. This is what to look for in next few weeks. From the last decade's playbook (good idea? different discussion)

cepr.org/publications/b…

cepr.org/publications/b…

Fed has been trying to get rid of the "original sin of QE" for a while. There is no contradiction between raising rates while expanding the balance sheet. Rather, tightening risks financial stability, which requires having an elastic balance sheet.

https://twitter.com/R2Rsquared/status/1576164361898708998

If:

(i) liquidity facilities to banks to stop runs +

(ii) QE market-making for MBS to stop fire sales

work, then interest rates can stay focussed on fighting inflation.

In that case, still expect peak rate of 5.5-6%, nothing really changed this past week

federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy…

(i) liquidity facilities to banks to stop runs +

(ii) QE market-making for MBS to stop fire sales

work, then interest rates can stay focussed on fighting inflation.

In that case, still expect peak rate of 5.5-6%, nothing really changed this past week

federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy…

Of course, if think that the Fed cannot stop a financial collapse, or that rescuing of a few banks will trigger a credit crunch, then this has a direct impact on inflation and the path for interest rates. Let's see in the next few weeks. Read up on crises

amazon.com/Crash-Course-C…

amazon.com/Crash-Course-C…

In the next FOMC meet, instead of the anticipated 25-50bp rise, for precaution instead 0-25bp is ok. Insofar as things calm down, can do 50bp next two meetings, stay on the same path, no material difference for inflation. But avoid financial dominance

economic-policy.org/76th-economic-…

economic-policy.org/76th-economic-…

IMHO, the large fall in the 2y rate in the last two days is either:

(i) markets over-reacting, as they have often done in this hiking cycle, and a correction will come soon, or

(ii) a flight to safety to government bonds raising debt revenue

aeaweb.org/articles?id=10…

(i) markets over-reacting, as they have often done in this hiking cycle, and a correction will come soon, or

(ii) a flight to safety to government bonds raising debt revenue

aeaweb.org/articles?id=10…

It would be hard to have such a steep hiking cycle without some cracks appearing in the financial system. As long as the cracks do not become crashes, monetary policy can stay the course to bring down inflation and avoiding financial dominance. As it has done so far.

End of🧵

End of🧵

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh