For those following along as we continue the countdown to #MatchDay2023, it’s now time for Part 4 in our six-part series.

Yesterday, I described how the NRMP did their best to ignore one doctor’s fight to make the matching algorithm applicant-optimal.

Today, I’ll explain why.

Yesterday, I described how the NRMP did their best to ignore one doctor’s fight to make the matching algorithm applicant-optimal.

Today, I’ll explain why.

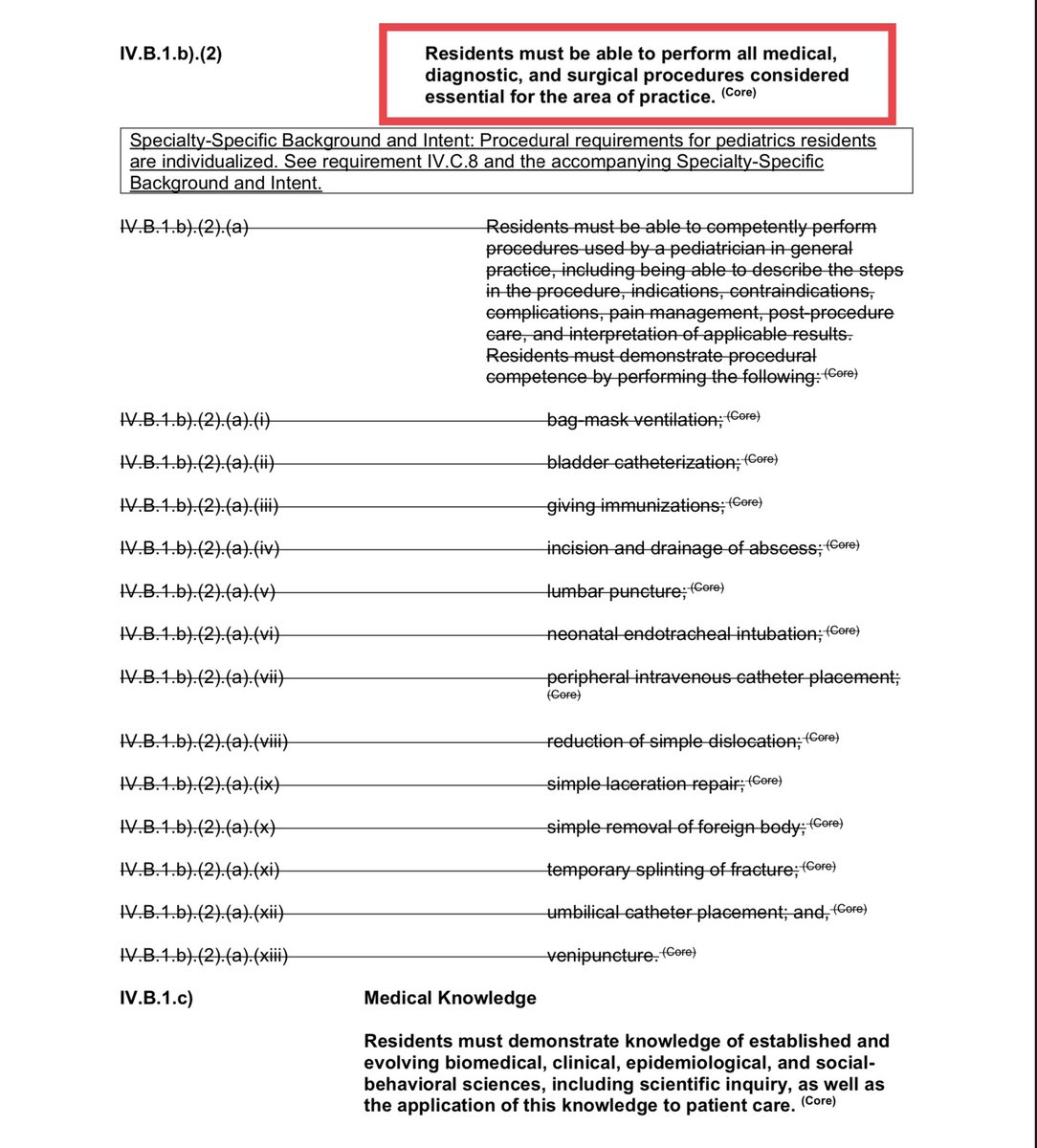

We’ll cover why outside-the-match offers threaten the existence of the match; how the GI fellowship match failed; and why the NRMP fought so hard for their “All In” policy.

It’s all here:

The Match, Part 4: Unraveling and going all in

It’s all here:

The Match, Part 4: Unraveling and going all in

If you missed yesterday’s thread, it’s here:

https://twitter.com/jbcarmody/status/1635317117573820416

And if you missed the earlier videos, let me help you get caught up:

The Match, Part 1: Why do we have a Match?

The Match, Part 2: The battle for the algorithm

The Match, Part 3: On marriages and matching

The Match, Part 1: Why do we have a Match?

The Match, Part 2: The battle for the algorithm

The Match, Part 3: On marriages and matching

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh