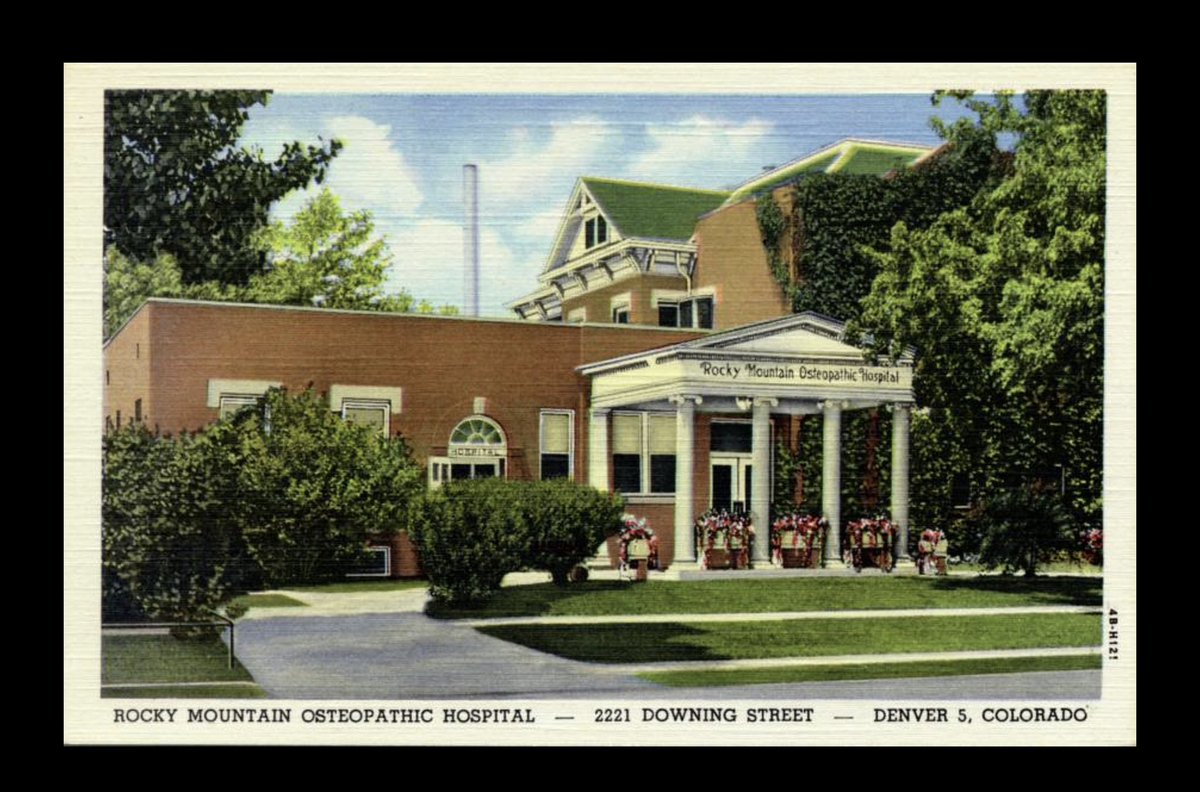

In 1998, a small residency program in Colorado lost its accreditation.

It wasn’t the kind of thing that you’d expect to change the course of academic medicine.

And yet, it *almost* did.

Earlier, I explained how the Match started. Now, I’ll tell you how it nearly collapsed.

🧵

It wasn’t the kind of thing that you’d expect to change the course of academic medicine.

And yet, it *almost* did.

Earlier, I explained how the Match started. Now, I’ll tell you how it nearly collapsed.

🧵

When the HealthONE family medicine residency shut down, the residents lost their jobs.

And some of them went to see an attorney named Sherman Marek.

marekweisman.com

And some of them went to see an attorney named Sherman Marek.

marekweisman.com

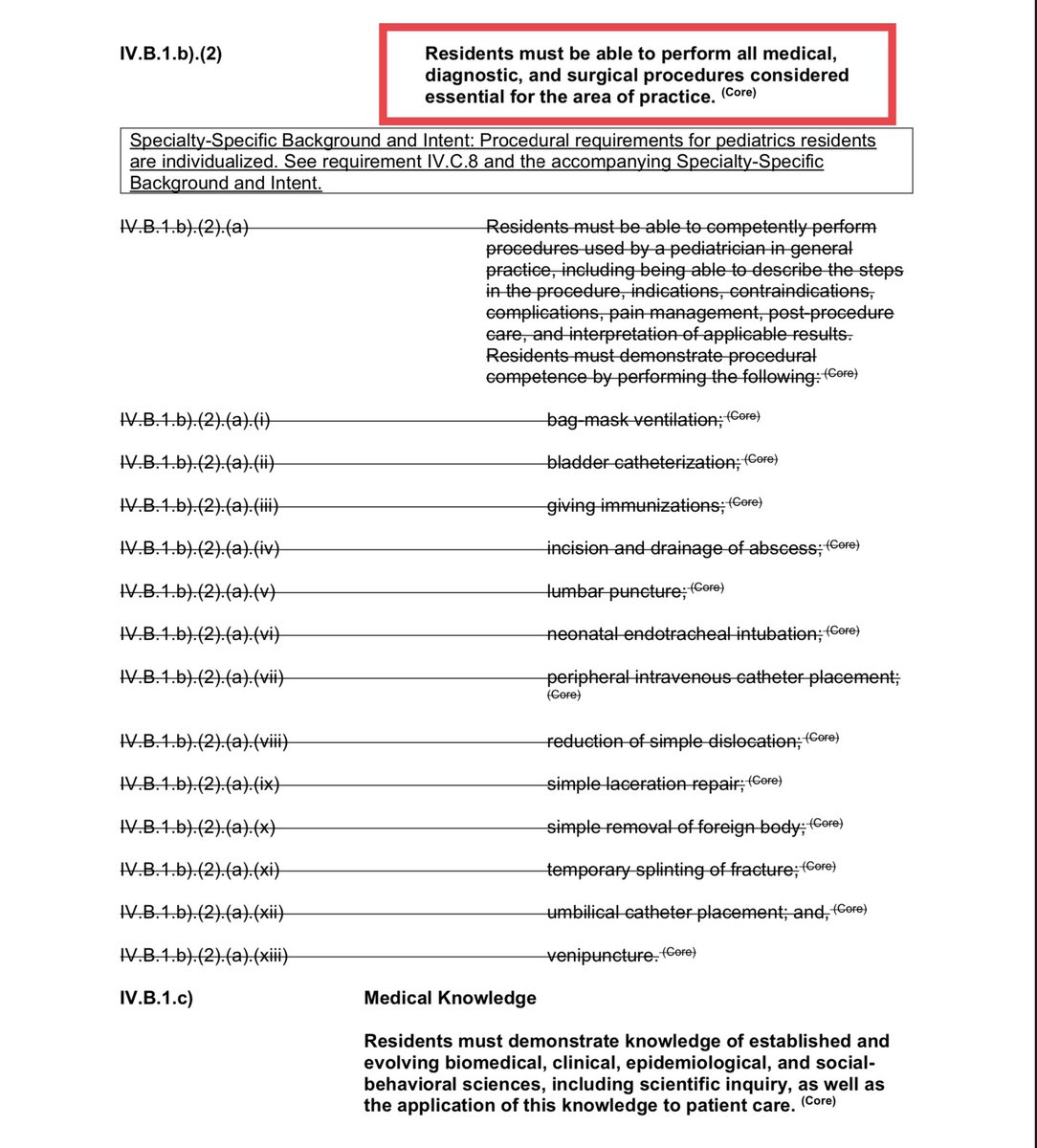

The stories these residents told about their program were jarring.

They were working almost unlimited hours for meager pay. But since they’d been assigned their position by a match, they’d accepted their contract sight unseen, without any chance to negotiate salary or hours.

They were working almost unlimited hours for meager pay. But since they’d been assigned their position by a match, they’d accepted their contract sight unseen, without any chance to negotiate salary or hours.

“This can’t be legal,” Marek thought. “There must be something I’m missing.”

Even after the residents’ case was over, Marek kept thinking about it.

And the more he thought about it, the more convinced he became that the match WASN’T legal.

It was a violation of antitrust law.

Even after the residents’ case was over, Marek kept thinking about it.

And the more he thought about it, the more convinced he became that the match WASN’T legal.

It was a violation of antitrust law.

On May 7, 2002, Marek filed a lawsuit in the U.S. District Court in Washington, DC, alleging that the actions of the AAMC, ACGME, and NRMP effectuated an anti-competitive conspiracy that suppressed resident wages below their true market value.

nytimes.com/2002/05/07/us/…

nytimes.com/2002/05/07/us/…

The suit went off like a bombshell in academic medicine - in part because the stakes were so high.

This was a class action suit. If the plaintiffs could prove that resident salaries had been suppressed by just $15,000/y, the defendants could be liable for damages of $9 BILLION.

This was a class action suit. If the plaintiffs could prove that resident salaries had been suppressed by just $15,000/y, the defendants could be liable for damages of $9 BILLION.

Damages like that would bankrupt the AAMC, ACGME, and NRMP a hundred times over.

So to ensure any judgment snared the defendants with pockets deep enough to pay the damages, the suit also named 29 individual hospitals - including some of the biggest names in all of medicine.

So to ensure any judgment snared the defendants with pockets deep enough to pay the damages, the suit also named 29 individual hospitals - including some of the biggest names in all of medicine.

Naming these institutional defendants was also logical - after all, it was ultimately the hospitals who benefitted from cheap resident labor.

But deep pockets can buy powerful allies.

And soon, the decision to include the hospitals in the suit would prove ominous.

But deep pockets can buy powerful allies.

And soon, the decision to include the hospitals in the suit would prove ominous.

The defendants mounted an aggressive technical legal defense - but ultimately, the court’s preliminary rulings refused to dismiss the key defendants from the suit.

The plaintiffs were gonna get their day in court - where legal scholars felt they had a strong chance of winning.

The plaintiffs were gonna get their day in court - where legal scholars felt they had a strong chance of winning.

Soon, rumors began to spread that the defendants were going to attempt an end-run.

Rather than fight in court, they were going to ask Congress to change the laws.

See again coverage by the New York Times:

nytimes.com/2003/08/18/us/…

Rather than fight in court, they were going to ask Congress to change the laws.

See again coverage by the New York Times:

nytimes.com/2003/08/18/us/…

The NYT article included this gem of a quote by the then-president of the AAMC.

(Because surely that’s what any of us would do if we were facing a frivolous lawsuit - we wouldn’t seize an easy courtroom victory, we’d call upon our powerful buddies in Congress to change the law!)

(Because surely that’s what any of us would do if we were facing a frivolous lawsuit - we wouldn’t seize an easy courtroom victory, we’d call upon our powerful buddies in Congress to change the law!)

This lobbying received an especially favorable reception from Senators Hillary Clinton (D-NY) and Ted Kennedy (D-MA) - whose districts were home to many of the named hospitals.

Four other senators sent a letter warning them not to try to get around the usual legislative process.

Four other senators sent a letter warning them not to try to get around the usual legislative process.

For a while, things were quiet.

Then, in April 2004, the Senate considered the Pension Funding Equity Act.

It was a dreary, mundane piece of legislation - but it had to be passed before Congress recessed, or else employers couldn’t calculate interest on their pension plans.

Then, in April 2004, the Senate considered the Pension Funding Equity Act.

It was a dreary, mundane piece of legislation - but it had to be passed before Congress recessed, or else employers couldn’t calculate interest on their pension plans.

But when the bill came to the floor for a vote, some senators noticed that the bill was different.

There had been a new amendment tacked on to the end.

This amendment gave the NRMP and other matching services a legislative exemption from current or future antitrust litigation.

There had been a new amendment tacked on to the end.

This amendment gave the NRMP and other matching services a legislative exemption from current or future antitrust litigation.

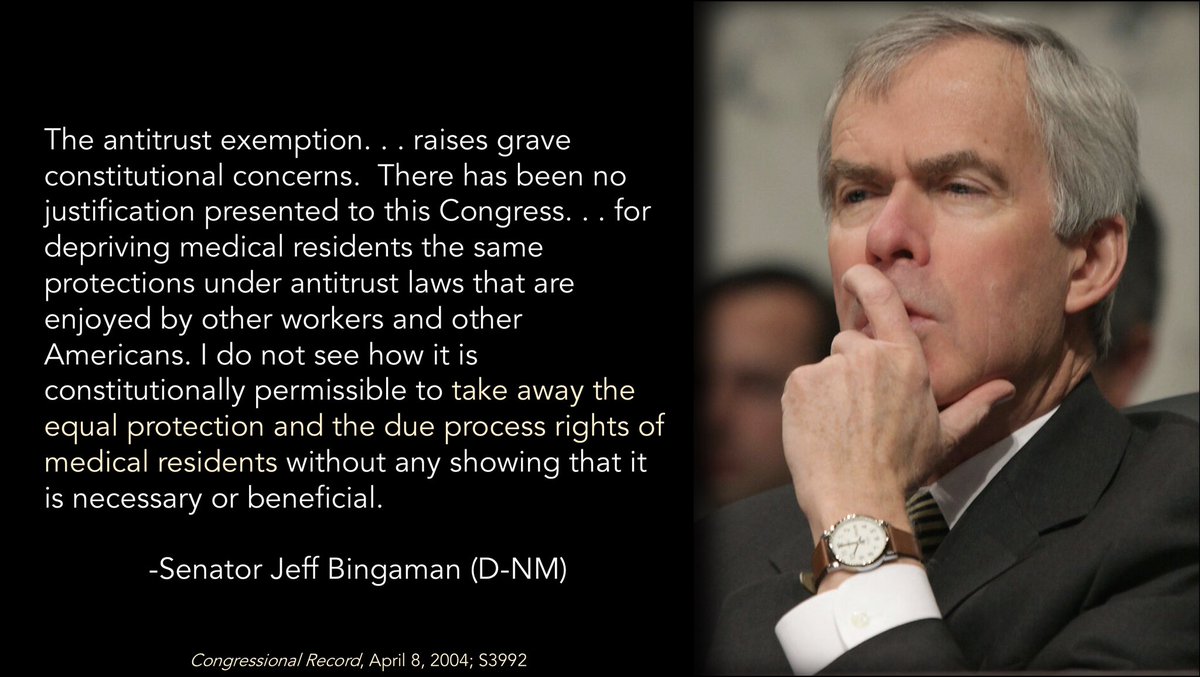

Several senators - including Russ Feingold (D-WI), Herb Kohl (D-WI), and Jeff Bingaman (D-NM), argued eloquently against including this last-minute provision.

But it was too late. Congress had to pass the bill’s major provisions, and it passed, 78-19.

But it was too late. Congress had to pass the bill’s major provisions, and it passed, 78-19.

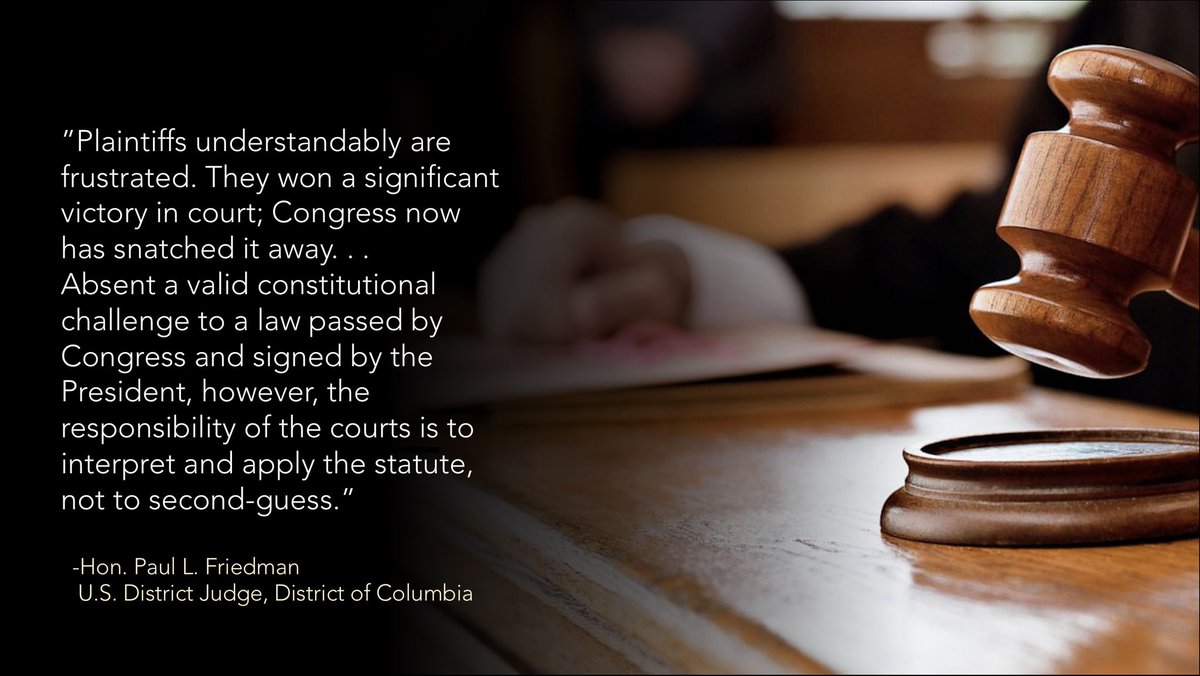

Noting that Congress had spoken, Judge Paul Friedman dismissed the lawsuit.

The Match was legal. At least, it was now.

The hospitals avoided a devastating financial blow.

The plaintiffs received an painful civics lesson.

And not much changed for residents - or their salaries.

The Match was legal. At least, it was now.

The hospitals avoided a devastating financial blow.

The plaintiffs received an painful civics lesson.

And not much changed for residents - or their salaries.

Some good emerged from Jung v. AAMC.

Amidst the lawsuit, the ACGME announced new duty hour restrictions for residents (the “80 hour workweek” that went into effect in 2003).

jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/…

Amidst the lawsuit, the ACGME announced new duty hour restrictions for residents (the “80 hour workweek” that went into effect in 2003).

jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/…

Of course, officially, this had nothing to do with the court case: the ACGME had been studying duty hour limits for nearly 2 decades.

But the final push over the finish line seemed to occur very rapidly - and it’s easy to imagine that certain pending litigation might’ve helped.

But the final push over the finish line seemed to occur very rapidly - and it’s easy to imagine that certain pending litigation might’ve helped.

Also, although residents still can’t really negotiate their contracts, the NRMP now requires programs to at least provide a copy of the contract that applicants will be required to sign before they Match.

If you made it this far, thanks for reading.

And if you want to read more: there’s more detail and links to some of the primary source material mentioned above on my site:

thesheriffofsodium.com/2021/03/03/the…

And if you want to read more: there’s more detail and links to some of the primary source material mentioned above on my site:

thesheriffofsodium.com/2021/03/03/the…

And if you’d prefer a video version to watch (or share), there’s one on YouTube:

The Match, Part 5: The lawsuit

The Match, Part 5: The lawsuit

And of course, come back tomorrow for the sixth and final installment of this series on the Match as we count down to #matchday2023.

/end

/end

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh