In a speech at @Columbia University, I discussed how monetary policy @ecb could be implemented in the future. I outlined the options available for maintaining control over short-term interest rates during balance sheet normalisation. This thread summarises my key points. 1/22

https://twitter.com/ecb/status/1640368392669478914

The launch of asset purchases and TLTROs in response to a long period of low inflation and to the pandemic resulted in a strong balance sheet expansion that was significant in historical and international comparison. 2/22

We estimate that balance sheet run-down will lead to excess liquidity being fully absorbed by 2029. At that point, the Eurosystem’s balance sheet would still be about three times the size it was in 2007, and it would need to increase again to meet growing currency demand. 3/22

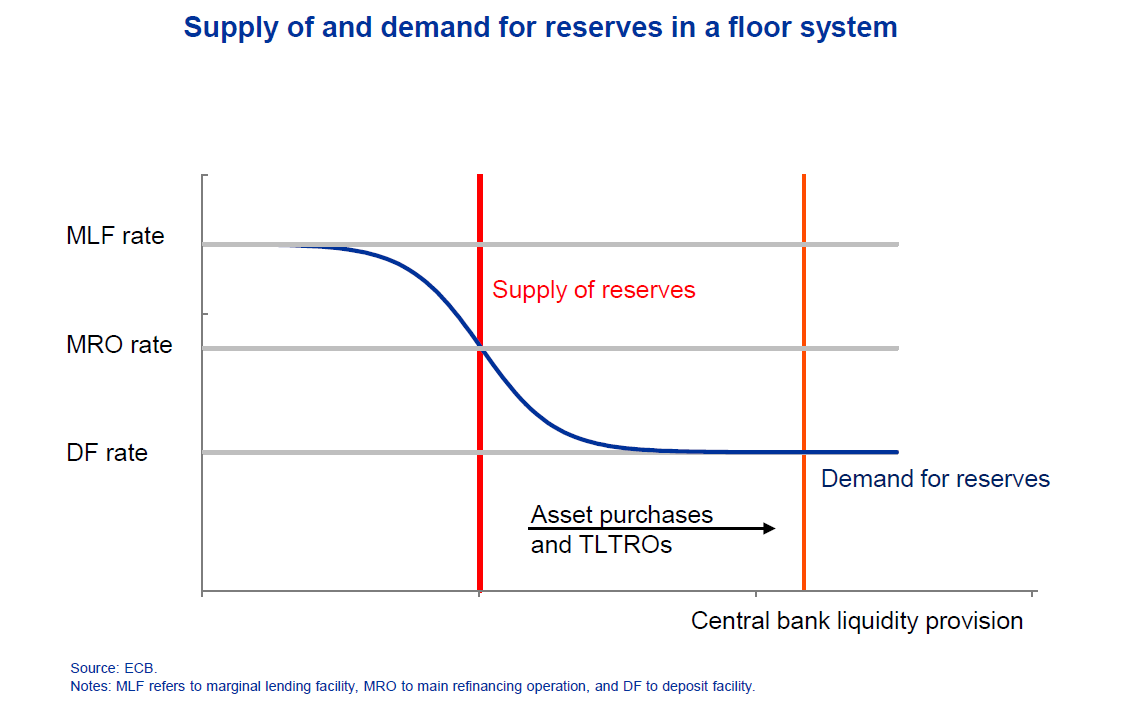

Changes in excess liquidity affect policy implementation. Before 2008 we steered overnight rates to the middle of the interest rate corridor by providing just enough reserves to meet banks’ liquidity needs. Balance sheet expansion pushed rates to the floor of the corridor… 4/22

… by raising the supply of reserves (see chart). Balance sheet run-down will reverse this, which will put upward pressure on interest rates at some point. The current large volume of excess reserves means that we should still be at a significant distance from that point. 5/22

Yet, banks’ demand for reserves is highly uncertain. Should their demand have changed more fundamentally, then upward pressure on interest rates may well start earlier than in the past. 6/22

The Swedish experience suggests that banks might want to hold more reserves in the future. Banks decided to hold a share of reserves in the deposit facility rather than purchasing certificates with a higher rate of remuneration, pushing rates to the floor of the corridor. 7/22

There are two main reasons for a higher demand for reserves. One is regulatory changes. The introduction of Basel III has resulted in an increase in the demand for HQLA. In the euro area, excess reserves currently account on average for 60% of HQLA holdings. 8/22

The second factor is precautionary demand. Overnight deposits have increased notably, raising the risks of withdrawals. Recently, funds have shifted from overnight to term deposits. Banks may want to hold liquidity buffers in reserves as these do not need to be liquidated. 9/22

Uncertainty about reserve demand means that a return to the pre-2008 corridor is difficult. In addition, tighter regulation and higher risk aversion may have permanently reduced the capacity of the euro area interbank market to efficiently distribute reserves across banks. 10/22

One alternative is to adopt the current floor system by maintaining ample reserves, like the Federal Reserve. This has three benefits: it maintains a higher level of safe assets in the financial system, it is operationally simple, and it can ensure instrument robustness. 11/22

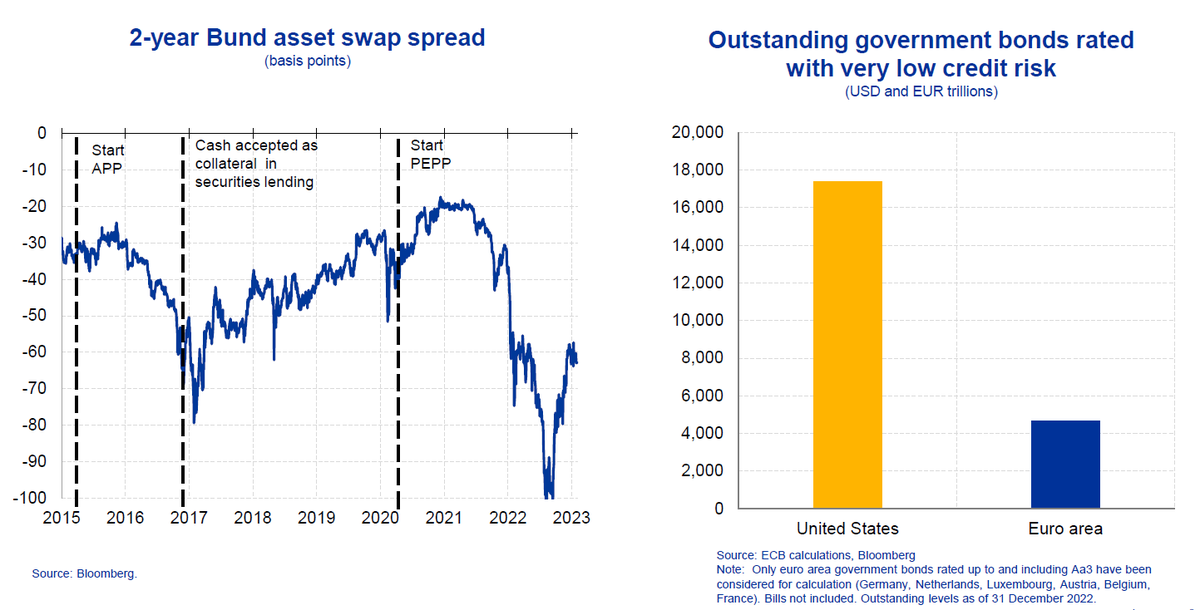

As not all financial market participants have access to the central bank balance sheet, the floor might be “leaky”. In the euro area, the benchmark interest rate, €STR, has increasingly decoupled from the DFR as reserves increased in the wake of the PEPP and the TLTROs. 12/22

Establishing the equivalent to the Fed’s ON RRP could improve rate controllability. But it could also affect the robustness of €STR, which heavily relies on banks’ trading with market participants who do not have access to the Eurosystem’s balance sheet. 13/22

Given the uneven reserve distribution the ECB would need to hold a large structural bond portfolio in a “supply-driven floor system” to avoid unwarranted interest rate volatility. This limits the options how to provide the reserves required to steer rates towards the floor. 14/22

A large structural portfolio raises concerns about monetary and fiscal interactions in a currency union. It may also affect the smooth functioning of financial markets as the euro area has a substantially lower volume of outstanding highly-rated and liquid bonds. 15/22

A second alternative to steer interest rates is to offer regular repo operations to ensure that shortfalls in banks' demand for reserves is replenished as QT proceeds. This is the “demand-driven” approach followed by @bankofengland, explained here: 16/22 bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/fi…

One advantage of such an approach is that it may lead to a more balanced reserve distribution, providing better insurance against fragmentation shocks. It also allows the central bank to provide reserves via a mix of a bond portfolio and credit operations. 17/22

Moreover, it could lead to a leaner balance sheet. This will depend on the collateral framework (i.e. the ability to mobilise non-HQLA assets as collateral) and the relative return on reserves. In recent months it was often more profitable for banks to hold marketable HQLA. 18/22

Finally, it allows to learn about banks’ liquidity needs and offers flexibility for adjustment. For example, a narrow corridor could encourage some market activity. Rate volatility from fluctuations in excess reserves may not affect broader monetary policy transmission. 19/22

But such a system would need to avoid stigma effects and provide backstop facilities for unexpected liquidity shocks in-between liquidity providing operations. 20/22

In line with an open market economy, the steady state balance sheet should only be as large as necessary to ensure sufficient liquidity provision and effectively steer short-term interest rates towards levels that are consistent with price stability over the medium term. 21/22

The speech can be found here: ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date…

The slides are found here: ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date…

A replay of the event can be watched here: sghmacro.com/media_event/a-…

And a great thanks to the ECB's markets team for their support! 22/22

The slides are found here: ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date…

A replay of the event can be watched here: sghmacro.com/media_event/a-…

And a great thanks to the ECB's markets team for their support! 22/22

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh