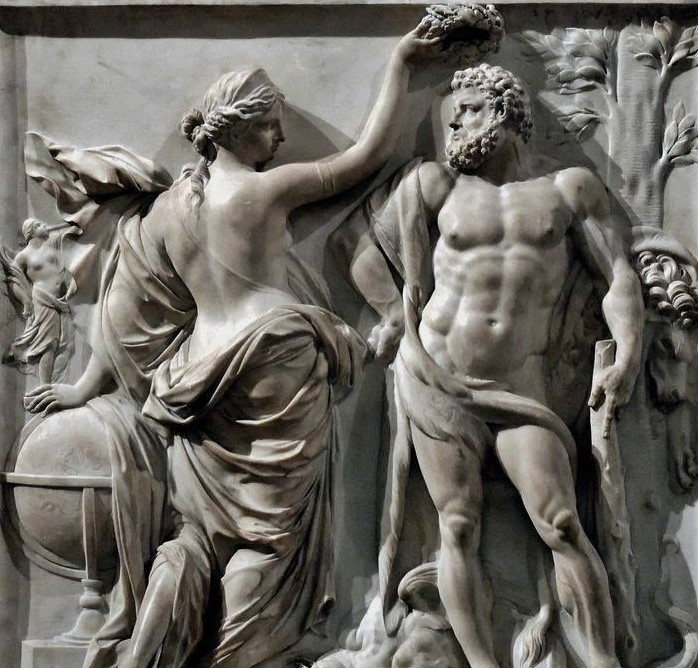

1/ In "Twilight of the Idols," the Great Zarathustra, Friedrich Nietzsche, writes: "The Greeks...created the concept of the aristocrat, and they produced a type that is incomparable and supreme: the noble human being, the aristos." 🧵

2/ The Greek concept of ἀρετή, arête ("excellence"), was not merely an abstract ideal, but a way of life and a mode of Being; it was the earthly representation of the pinnacle of human achievement.

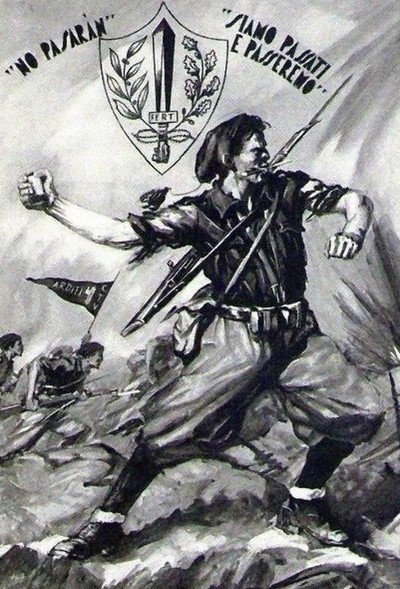

3/ The writings of Homer gave birth, and external form, to a new vision of human greatness — a vision that was brought to life and made manifest within the flesh and blood of the ἄριστος, the Aristos ("the best; noblest"), the aristocratic warrior of ancient Hellas."

4/ In this thread, we shall delve into the realm of the Aristos and explore sublime Aristocratic Ideals that thrived in the ancient Greek world. Our aim is to understand and internalize these ideals, embodying them within ourselves as we strive for personal elevation.

5/ Any exploration of the Greek world begins and ends with the epic writings of Homer. It is through his writings that we will embark on a journey towards aristocratic transfiguration, with the philosophy of Nietzsche playing a prominent role in our odyssey.

6/ For the Aristos, self-mastery is the key element in embracing arête, and as such, it requires the cultivation of the necessary inner strength and courage to overcome all limitations, vis-à-vis a Nietzschean Will to Power.

7/ The Aristocratic Ideal of arête was central and fundamental to Homer's epic poems, the "Iliad" and the "Odyssey." In the "Iliad," Achilles, the Aristos par excellence, is portrayed as possessing "the arete of body and of soul" and "the thumos of a lion."

8/ The term thumos, θυμός, denotes spiritedness or a passionate desire to excel. It is through the fiery thumos, much like that of Achilles, that Alexander the Great carved out his great conquests, becoming the embodiment of the conquering spirit.

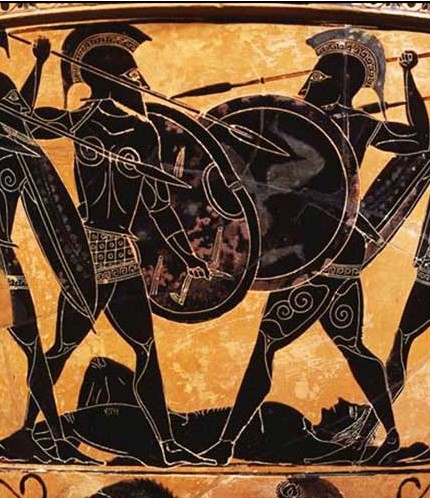

9/ Achilles' arête was evident in his skill as a warrior. With his spear and shield, he carved his way through countless foes, leaving no doubt of his superiority. As Homer recounts in the Iliad: "And now he charges like a god of war, Laying low the fighters left and right."

10/ However, Achilles exercised his arête not only through his execution of martial prowess but also through sagacity in battle. As such, Achilles possessed the wisdom to know when to fight, and when to refrain from the struggle of combat.

11/ Homer writes, "Achilles drew the great sword from his thigh and was about to dash among the foremost fighters, but Athena came to him from heaven... and spoke to him: 'Do not, by any means, even for a moment, set upon the Trojans and fight with them.'"

12/ For Nietzsche, arête was the pursuit of self-mastery and creation. He saw arête as a manifestation of the Will to Power, the driving force underlying all human action and creation. To achieve arête was to exercise one's Will to Power and to become a "master of oneself."

13/ In the pursuit of the Greek Aristocratic Ideal, the concept of τόλμα, tolma ("daring"; "I dare") also holds significant importance. In the "Iliad," the daring bravery of Hector is praised when he says –

14/ –"Even when my spirit tells me to stand and fight no longer, I will have to disregard it and win glory, or die." By disregarding his own fear, and pushing himself to achieve glory, Hector demonstrates the importance of tolma, of daring courage, in the pursuit of excellence.

15/ For Nietzsche, tolma is a vital component of his vision of the Übermensch, the Overman, the ideal of human perfection and excellence. The Übermensch is one who possesses the courage and herculean strength to pursue excellence with unwavering determination and daring.

16/ Another fundamental principle of the Aristoi is τιμή, timē ("honor"; "reverence"). In the "Iliad," the mighty Achilles famously declared that his "timē comes before his life." Achilles was the personification of the principle "death before dishonor."

17/ For the ancient Hellenes and all true aristocrats throughout history, honor is not a mere abstraction, but rather an elemental aspect of being. It is a manifestation of noble character, unyielding courage, and an unwavering commitment to excellence.

18/ For Nietzsche, honor was not a passive state of Being, but an active pursuit of greatness and distinction. It was a manifestation of the individual's Will to Power, a reflection of their inner strength, courage, and self-mastery.

19/ Nietzsche believed that the pursuit of timē, of honor required the constant struggle against the forces of complacency, conformity, and mediocrity, and as such, it was a celebration of the exceptional. In Nietzsche's own words, "The noble soul has reverence for itself."

20/ The Aristocratic Ideal of κλέος, kleos ("glory"), was vital to the Aristos. In the "Iliad," Achilles' pursuit of kleos is evident in his willingness to sacrifice his life for the sake of glory when he says, "My fate is to live a short life, but to achieve everlasting glory."

21/ Odysseus, the epic protagonist of the "Odyssey," is another prime example of someone who seeks glory, but in a sense beyond the utilization of martial prowess. In Book VIII of the "Odyssey," he is welcomed to the court of King Alcinous of the Phaeacians —

22/ — where he is asked to recount his fantastic adventures. Through his storytelling, Odysseus is able to achieve glory, and thus gain the admiration and respect of his audience. The bards of the "Odyssey" also sing of the kleos of heroes such as Achilles, Agamemnon, and Ajax.

23/ In Nietzsche's view, the pursuit of kleos, or glory, is an expression of the Will to Power. By striving for eternal glory and renown, the Aristos' asserts self-mastery over themselves and dominance over the world.

24/ The Aristocratic Ideal of ἀνδρεία, andreia ("courage"; "manly spirit") is another of the timeless attributes of all aristocrats, both past & present. Homer's "Iliad" provides numerous examples of courage and bravery in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds.

25/ One of the most iconic examples of andreia, or courage, in the "Iliad" is expressed by the Trojan prince Hector. Despite facing the wrath of the Greek hero Achilles, Hector shows no fear, and instead, he courageously confronts his foe.

26/ Hector had slain Patroclus, the kinsmen and inseparable companion of Achilles, triggering the famed fury of Achilles. Despite this, Hector does not cower in fear. Instead, he displays great andreia and bravely confronts his adversary.

27/ In Book 22 of the "Iliad", Hector is described as "fierce as a bloodthirsty lion," and he is not afraid to face Achilles in single combat, even though he knows that the odds are overwhelmingly stacked against him, and death to be almost certain.

28/ For Nietzsche the pursuit of andreia is not just about physical courage in battle, but more broadly encompasses the courage to face the challenges of life with a "manly spirit." Hector embodies this ideal, not just a warrior but also as a husband, father, and great leader.

29/ Nietzsche believed that true greatness and power comes from the balance between pursuing both kleos ("glory") and andreia ("courage"), rather than favoring one over the other. It is the harmonious syncretism of the two which endows the Aristos with noble ferocity.

30/ In “The Struggle between Science and Wisdom” Nietzsche writes: “The Greeks progressed quickly, but they likewise declined with frightening quickness. When the Hellenic genius had exhausted its highest types, Greece declined with the utmost rapidity."

31/ As the heirs to noble Hellas, by embracing principles inherent to the Aristocratic Ideals of our forefathers, we can, and will become the Nietzschean bridge from whence Western Civilization is revitalized & restored to its former majestic glory.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh