Riding the Tiger. Writer & Translator.

https://t.co/ZHLU66URd1

19 subscribers

How to get URL link on X (Twitter) App

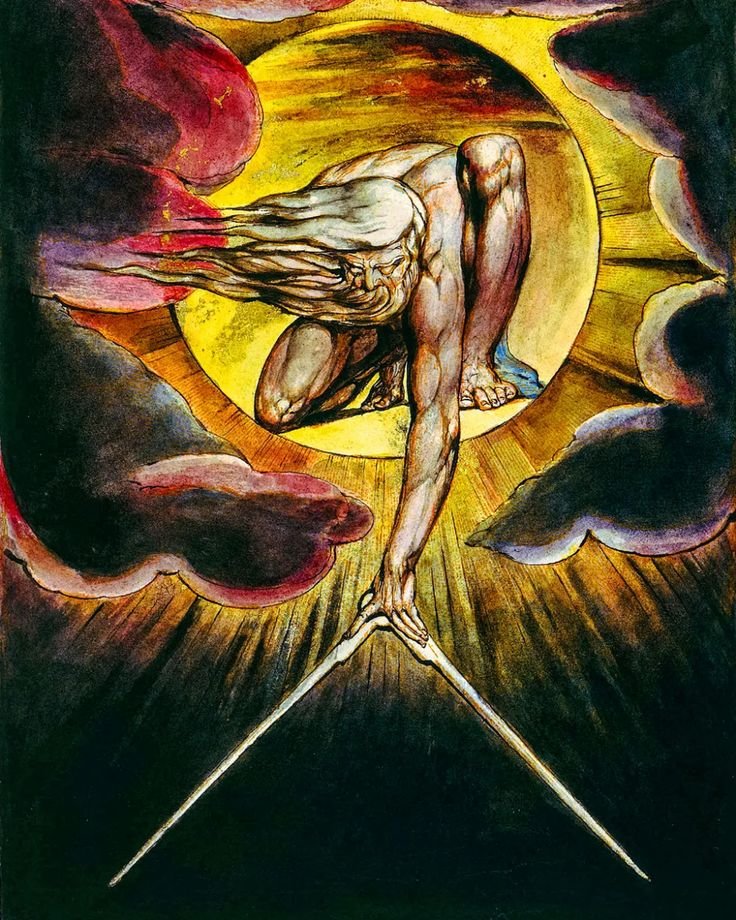

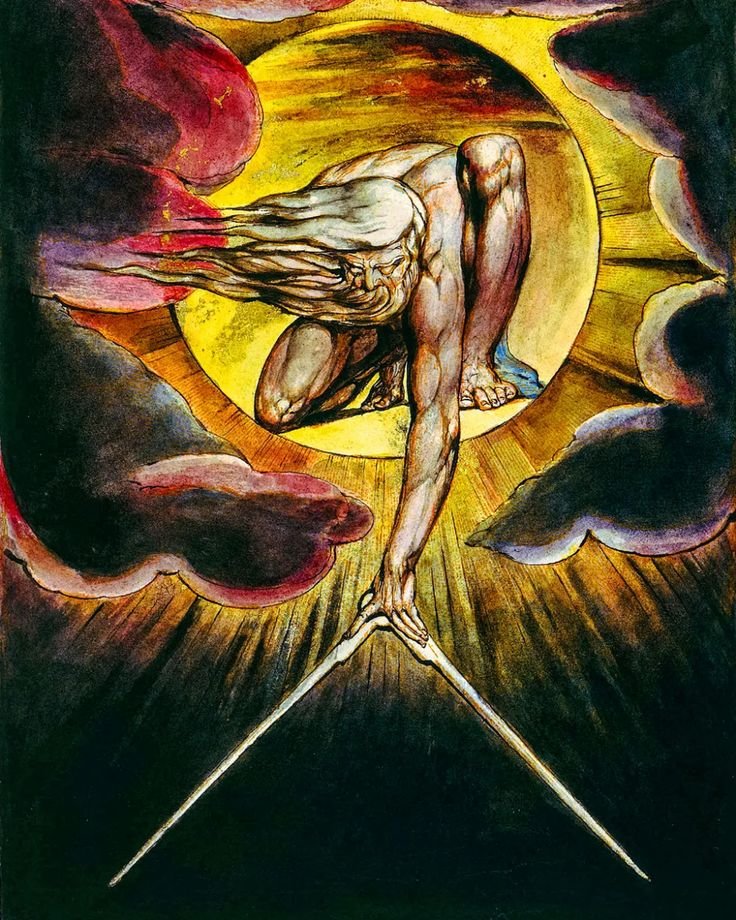

Civilization is shaped by many forces, yet its foundation is ALWAYS biological. It is the living soil from which culture rises, the inherited substance made visible in the world.

Civilization is shaped by many forces, yet its foundation is ALWAYS biological. It is the living soil from which culture rises, the inherited substance made visible in the world.

Reply # 1: Judgment and Corruption

Reply # 1: Judgment and Corruptionhttps://x.com/i/status/2003131091721294058

2/ The absurd notion that “America is an idea” is one that we hear often. It is peddled by the self-hating and the resentful alike, repeated by those too narrow of mind or too governed by ethnic interest to confront the plain historical record.

2/ The absurd notion that “America is an idea” is one that we hear often. It is peddled by the self-hating and the resentful alike, repeated by those too narrow of mind or too governed by ethnic interest to confront the plain historical record.

https://x.com/CCrowley100/status/1980787348674867459

2/ In its surface structure, The Age of Entitlement is a history of America from the assassination of John F. Kennedy to the rise of Donald Trump. But beneath its chronology lies a moral and constitutional argument of far greater consequence. Caldwell shows how the civil rights movement, ostensibly a campaign for racial equality, became the model for an entirely new form of governance in which law is subordinate to moral feeling and the state exists to enforce a vision of universal redemption. What began as an appeal to conscience was institutionalized as a bureaucracy of coercion. Out of the ruins of segregation arose a new elite of administrators, judges, and corporate patrons who discovered that the rhetoric of justice could serve as the instrument of power.

2/ In its surface structure, The Age of Entitlement is a history of America from the assassination of John F. Kennedy to the rise of Donald Trump. But beneath its chronology lies a moral and constitutional argument of far greater consequence. Caldwell shows how the civil rights movement, ostensibly a campaign for racial equality, became the model for an entirely new form of governance in which law is subordinate to moral feeling and the state exists to enforce a vision of universal redemption. What began as an appeal to conscience was institutionalized as a bureaucracy of coercion. Out of the ruins of segregation arose a new elite of administrators, judges, and corporate patrons who discovered that the rhetoric of justice could serve as the instrument of power.

2/ The Rising lasted six days. The Volunteers and members of the Irish Citizen Army held public buildings across Dublin, but artillery and gunfire soon reduced them to ruins. Civilian casualties mounted into the hundreds, and public opinion turned against the insurgents. On April 29 Pearse surrendered. He and the other leaders were court-martialed and executed in early May, among them James Connolly, already so badly wounded that he had to be tied to a chair before the firing squad. At first the people of Dublin spat upon the defeated Volunteers. Yet as the executions followed one after another, and as British guns shelled the city as though it were an enemy capital, sympathy shifted. The men once denounced as criminals became martyrs, and their deaths gave life to a Republic that had not yet existed in fact.

2/ The Rising lasted six days. The Volunteers and members of the Irish Citizen Army held public buildings across Dublin, but artillery and gunfire soon reduced them to ruins. Civilian casualties mounted into the hundreds, and public opinion turned against the insurgents. On April 29 Pearse surrendered. He and the other leaders were court-martialed and executed in early May, among them James Connolly, already so badly wounded that he had to be tied to a chair before the firing squad. At first the people of Dublin spat upon the defeated Volunteers. Yet as the executions followed one after another, and as British guns shelled the city as though it were an enemy capital, sympathy shifted. The men once denounced as criminals became martyrs, and their deaths gave life to a Republic that had not yet existed in fact.

2/ Yet immigration, though decisive, is not the whole cause of our crisis. We must face the harder truth that much of our demographic decline arises from within. Fertility among Western peoples fell before mass migration became overwhelming. The sickness is internal. To understand it, we must return to the origins of our social order.

2/ Yet immigration, though decisive, is not the whole cause of our crisis. We must face the harder truth that much of our demographic decline arises from within. Fertility among Western peoples fell before mass migration became overwhelming. The sickness is internal. To understand it, we must return to the origins of our social order.

2/ Schmitt’s first lesson is that conflict cannot be abolished. In “The Concept of the Political” he argued that political life arises from the distinction between friend and enemy, from the ability of a people to recognize those who threaten its existence and to affirm its own being against them. He did not glorify violence, nor did he celebrate war as a positive ideal. His point was sharper: that enmity is a permanent possibility, an irreducible horizon of collective life. No matter how refined institutions become, no matter how elaborate treaties appear, human groups will always find differences they regard as worth defending with their lives. Order itself rests upon acknowledging this fact, for to deny it is to prepare the ground for collapse.

2/ Schmitt’s first lesson is that conflict cannot be abolished. In “The Concept of the Political” he argued that political life arises from the distinction between friend and enemy, from the ability of a people to recognize those who threaten its existence and to affirm its own being against them. He did not glorify violence, nor did he celebrate war as a positive ideal. His point was sharper: that enmity is a permanent possibility, an irreducible horizon of collective life. No matter how refined institutions become, no matter how elaborate treaties appear, human groups will always find differences they regard as worth defending with their lives. Order itself rests upon acknowledging this fact, for to deny it is to prepare the ground for collapse.

2/ The Act raises the wage floor for H-1B workers to $150,000, stripping away the incentive for corporations to import foreigners at half the cost of Americans. Either companies pay the higher wage and prove these workers are truly exceptional, or they hire Americans at a fair market rate.

2/ The Act raises the wage floor for H-1B workers to $150,000, stripping away the incentive for corporations to import foreigners at half the cost of Americans. Either companies pay the higher wage and prove these workers are truly exceptional, or they hire Americans at a fair market rate.

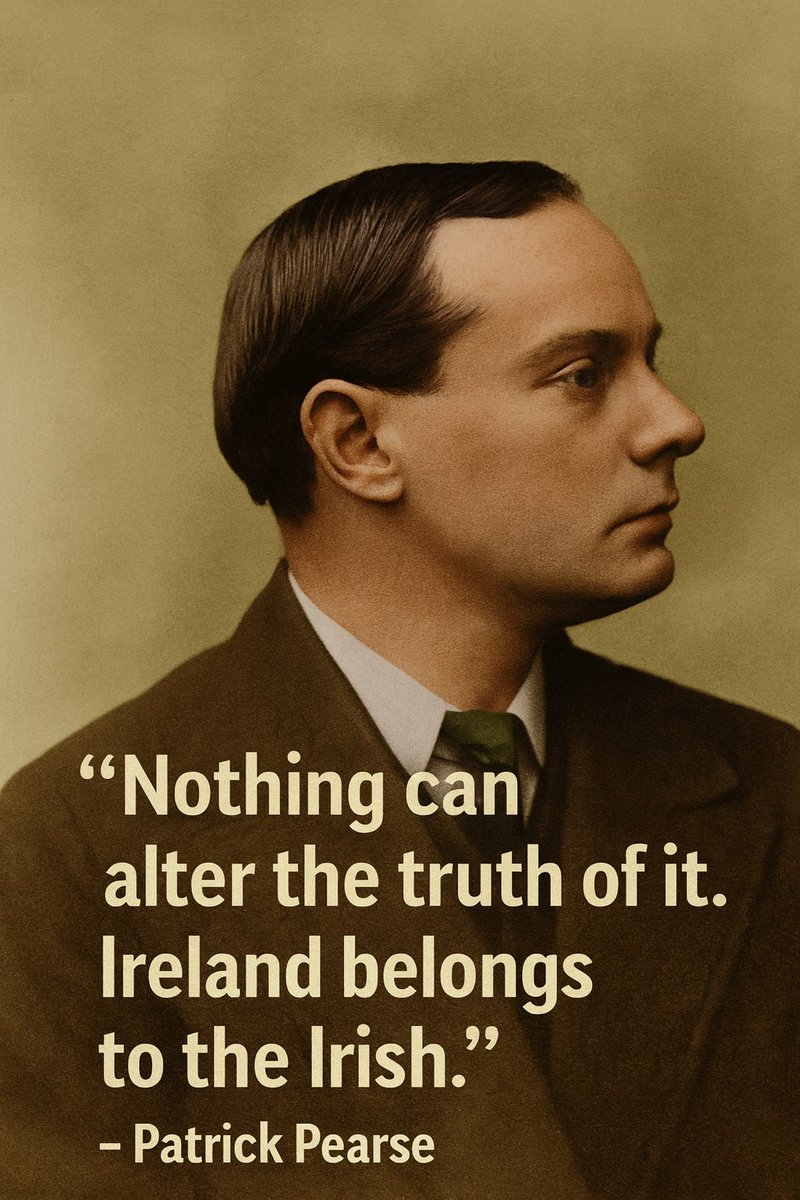

2/ Deneen situates his argument within a much older problem, one that the Greeks themselves faced. Their cities were repeatedly consumed by class struggle, oligarchs contending with democrats, at times resorting to the annihilation of rivals. From such experience came the first attempts to understand politics as the art of restraining conflict by cultivating the virtues of each class while suppressing their vices.

2/ Deneen situates his argument within a much older problem, one that the Greeks themselves faced. Their cities were repeatedly consumed by class struggle, oligarchs contending with democrats, at times resorting to the annihilation of rivals. From such experience came the first attempts to understand politics as the art of restraining conflict by cultivating the virtues of each class while suppressing their vices.

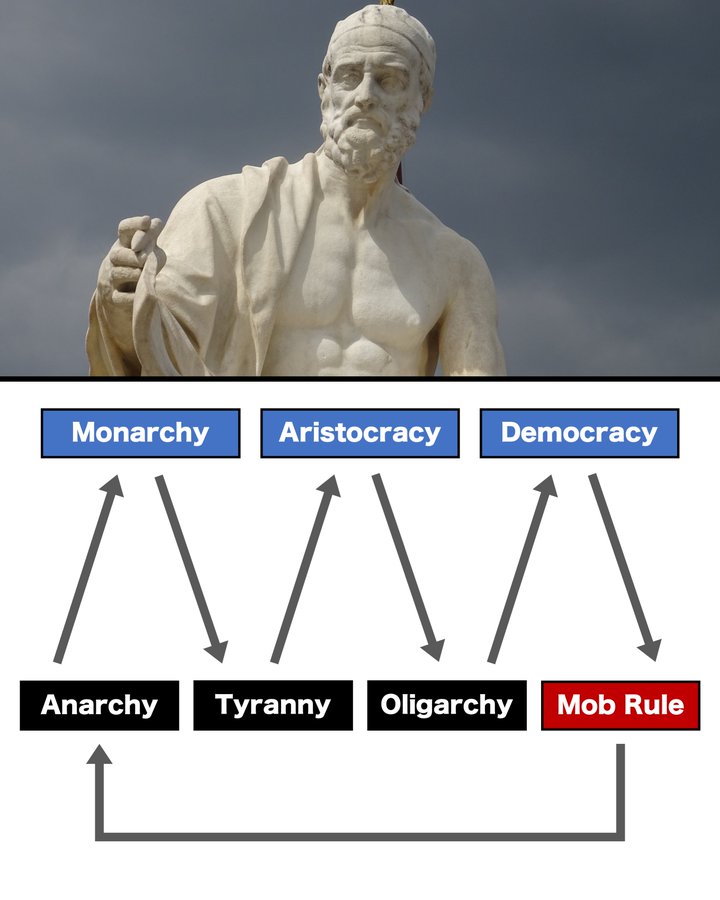

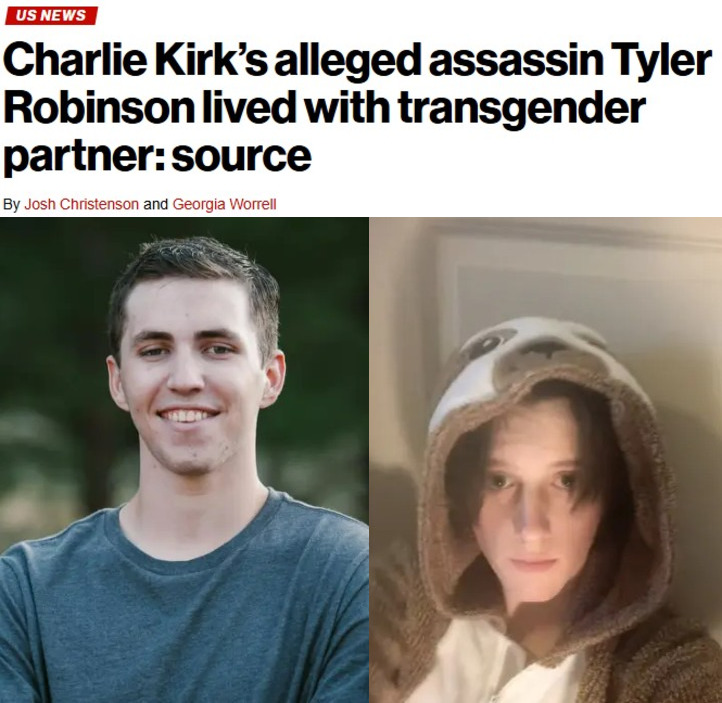

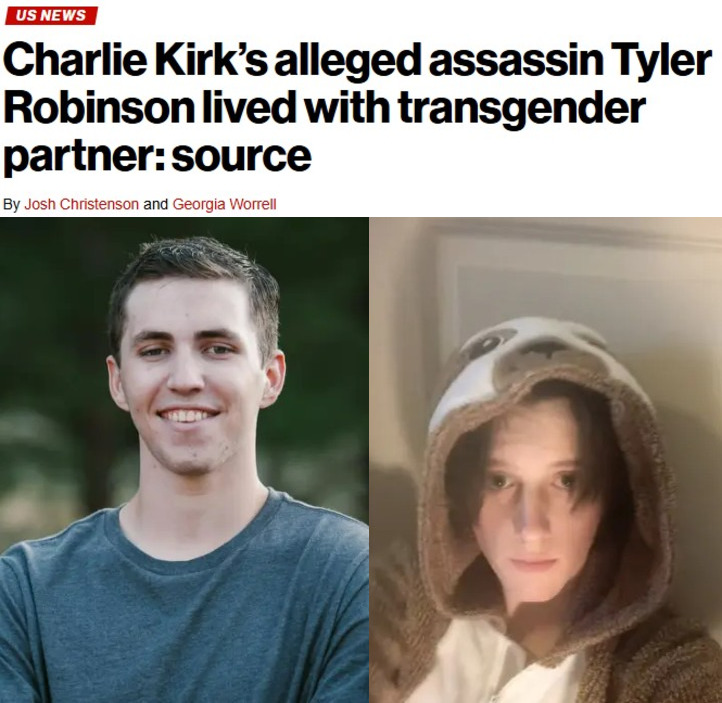

2/ The first evidence of this madness is found in the most basic truths of biology. A man cannot become a woman, nor a woman a man. Chromosomes remain immutable, XY for the male and XX for the female. Hormonal manipulation does not rewrite the code of life, nor can surgery replace the natural form with its opposite.

2/ The first evidence of this madness is found in the most basic truths of biology. A man cannot become a woman, nor a woman a man. Chromosomes remain immutable, XY for the male and XX for the female. Hormonal manipulation does not rewrite the code of life, nor can surgery replace the natural form with its opposite.

2/ History does not repeat itself in the same form, yet it does return in cycles, presenting the same crises beneath new appearances. The comparison between America and Weimar is therefore not about tracing replicas but about recognizing recurring patterns. The fractures of legitimacy, the collapse of confidence, the descent of politics into open struggle are not unique to Germany after the Great War. They reappear wherever a people, and thus a civilization, has lost faith in its continuity. The names change, the costumes change, but the underlying drama is the same.

2/ History does not repeat itself in the same form, yet it does return in cycles, presenting the same crises beneath new appearances. The comparison between America and Weimar is therefore not about tracing replicas but about recognizing recurring patterns. The fractures of legitimacy, the collapse of confidence, the descent of politics into open struggle are not unique to Germany after the Great War. They reappear wherever a people, and thus a civilization, has lost faith in its continuity. The names change, the costumes change, but the underlying drama is the same.

2/ Women and slaves, he writes, “delight in being flattered.” They welcome rulers who indulge them, where law is lax, discipline is weak, and authority bends to those who by nature should be ruled rather than ruling.

2/ Women and slaves, he writes, “delight in being flattered.” They welcome rulers who indulge them, where law is lax, discipline is weak, and authority bends to those who by nature should be ruled rather than ruling.

2/ The “Timaeus” opens as a sequel, carrying forward the conversation of Plato’s most celebrated work, the “Republic.” On the previous day Socrates had described the ideal city, its classes and laws, its guardians and its rulers. Yet he remains unsatisfied. What has been drawn in speech remains fixed, like painted figures that suggest life but lack motion. He therefore asks his companions to animate the city, to set it in action, and to show how it would contend with other states.

2/ The “Timaeus” opens as a sequel, carrying forward the conversation of Plato’s most celebrated work, the “Republic.” On the previous day Socrates had described the ideal city, its classes and laws, its guardians and its rulers. Yet he remains unsatisfied. What has been drawn in speech remains fixed, like painted figures that suggest life but lack motion. He therefore asks his companions to animate the city, to set it in action, and to show how it would contend with other states.

2/ At the heart of Buchanan’s warning lies the demographic collapse of the American nation. In the chapters “The End of White America” and “Demographic Winter,” he traces the dual catastrophe of declining White fertility and the relentless surge of non-White immigration. What he foresaw is now evident: replacement is not a theory but a measurable fact. The birthrates of European-descended Americans have fallen below replacement, while the gates have remained open to millions from the global South. The transformation, once projected for mid-century, is already visible in every major city and in much of the countryside besides.

2/ At the heart of Buchanan’s warning lies the demographic collapse of the American nation. In the chapters “The End of White America” and “Demographic Winter,” he traces the dual catastrophe of declining White fertility and the relentless surge of non-White immigration. What he foresaw is now evident: replacement is not a theory but a measurable fact. The birthrates of European-descended Americans have fallen below replacement, while the gates have remained open to millions from the global South. The transformation, once projected for mid-century, is already visible in every major city and in much of the countryside besides.

2/ What became of the founding people of America? Not the mythic immigrant multitude praised in modern textbooks, but the English stock that planted the first parishes, drafted the earliest colonial charters, fought the Indian wars, and declared independence in their own tongue and on their own terms. In “The WASP Question” Andrew Fraser asks with sober clarity why the Anglo-Saxon Protestant, once master of the institutions he created, now moves through their remnants as though he were only a guest.

2/ What became of the founding people of America? Not the mythic immigrant multitude praised in modern textbooks, but the English stock that planted the first parishes, drafted the earliest colonial charters, fought the Indian wars, and declared independence in their own tongue and on their own terms. In “The WASP Question” Andrew Fraser asks with sober clarity why the Anglo-Saxon Protestant, once master of the institutions he created, now moves through their remnants as though he were only a guest.

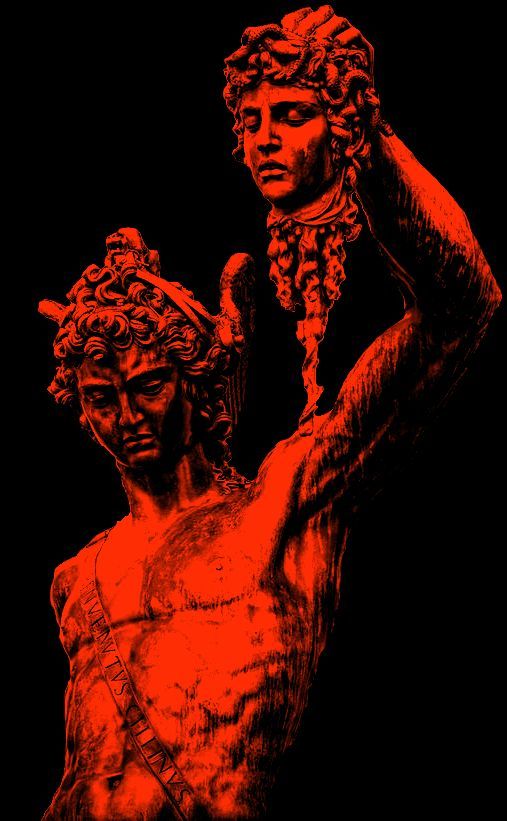

2/ To strive for renown was never simply to indulge pride or to advance the clan by cunning calculation. It was to place oneself before the eyes of gods and men, to gamble one’s life against time itself. When a man distinguished himself, his triumphs magnified the strength of his kin and secured the continuation of the tribe. Women sought the one whose name resounded louder than the rest, for in him they saw not merely a protector but the very fountain of life renewed. Yet this striving cannot be reduced to what modern science calls reproductive fitness, for the heroic impulse often cut against survival.

2/ To strive for renown was never simply to indulge pride or to advance the clan by cunning calculation. It was to place oneself before the eyes of gods and men, to gamble one’s life against time itself. When a man distinguished himself, his triumphs magnified the strength of his kin and secured the continuation of the tribe. Women sought the one whose name resounded louder than the rest, for in him they saw not merely a protector but the very fountain of life renewed. Yet this striving cannot be reduced to what modern science calls reproductive fitness, for the heroic impulse often cut against survival.