Science behind the Study:

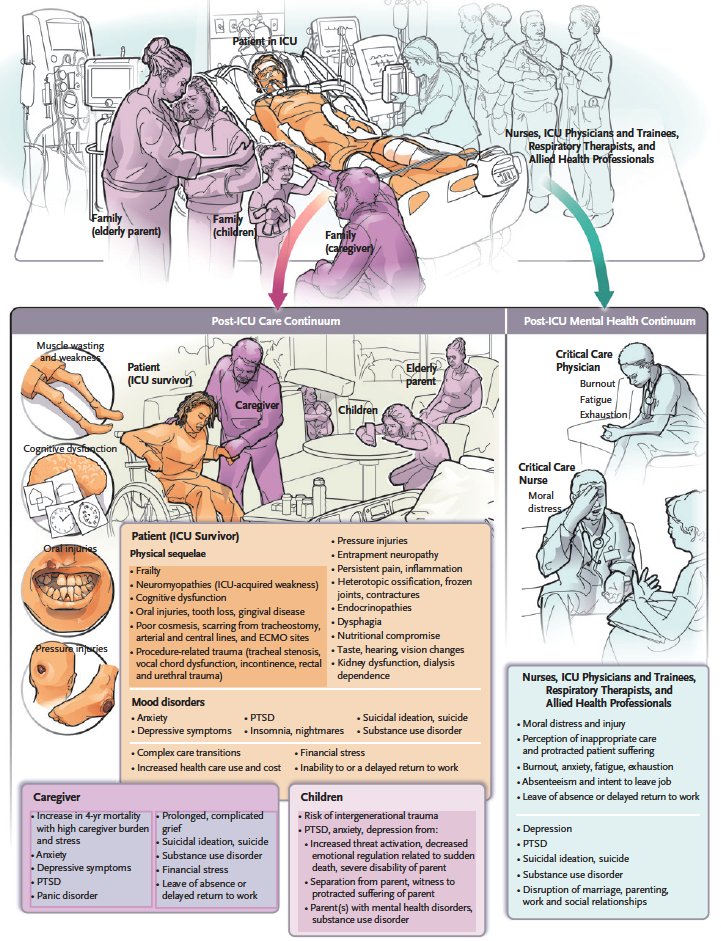

#GastricCancer is a common and often lethal cancer that, like cervical and liver cancer, can be attributed in large part to an infectious cause.

Full editorial on gastric cancer risk available here: nej.md/3JQQY4v 1/15

#GastricCancer is a common and often lethal cancer that, like cervical and liver cancer, can be attributed in large part to an infectious cause.

Full editorial on gastric cancer risk available here: nej.md/3JQQY4v 1/15

In the case of gastric cancer, the infectious agent is a bacterium, Helicobacter pylori. Until now, hereditary forms of gastric cancer were thought to be limited to a small percentage of CDH1-mutant cases. 2/15

In this week’s issue of NEJM, Usui et al. provide compelling evidence for a substantial contribution from inherited (germline) variants in nine cancer genes to the risk of gastric cancer. Read the study here: nej.md/40Br5MC 3/15

They found that pathogenic variants in genes were much more common among patients with gastric cancer than in the general population, and these variants “collaborated” with H. pylori infection to strongly elevate the risk of gastric cancer. 4/15

These findings imply that the hereditary contribution to the risk of gastric cancer is more important than previously believed and suggests that DNA damage induced by H. pylori, if repaired incorrectly or not at all, is a major driver of gastric carcinogenesis. 5/15

Environmental exposures are believed to drive the vast majority of cases of gastric cancer; in contrast, hereditary germline mutations were previously assumed to account for only 1 to 3% of cases of gastric cancer. 6/15

The concept that gastric cancer largely lacks a hereditary component — and that hereditary cancer syndromes confer a predisposition to breast, ovarian, and colon cancer but not to gastric cancer — is fundamentally challenged by the study by Usui et al. 7/15

The futile attempts of the host to eradicate an H. pylori infection fuel chronic gastric inflammation, which may progress to chronic atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia. 8/15

Although such immunopathologic lesions are well-documented precursor lesions of the “intestinal type” of gastric cancer, H. pylori is also known to have genotoxic activity that is likely to contribute to malignant transformation of gastric epithelial cells. 9/15

The genotoxicity of H. pylori depends in large part on its expression of a functional T4SS and is readily detected in cultured gastric cell lines, organoid cells, and biopsy specimens from patients with H. pylori–induced chronic gastritis. 10/15

H. pylori–induced DNA damage manifests in the form of DNA double-strand breaks that are evident as discontinuities in metaphase chromosomes and through evidence of attempts by the damaged cell to repair its double-strand breaks. 11/15

Two major pathways of H. pylori–induced double-strand breaks have been described; these pathways are complex and likely to be complementary, and they predominantly affect cells during a specific phase of the cell cycle (S phase). 12/15

Although the DNA-damaging activity of H. pylori was first described more than a decade ago, it is only now — thanks to Usui et al. — that we are finally beginning to understand how DNA damage induced by the pathogen promotes malignant transformation. 13/15

It does so in the context of hereditary homologous recombination deficiency. In this respect, it is an example of “multihit” carcinogenesis, in that two or more “hits” are required for cancer to occur. 14/15

Read “A Double Whammy on Gastric Cancer Risk” by Anne Müller, Ph.D., and Jiazhuo He, M.D.: nej.md/3JQQY4v 15/15

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter