Supercharge your paper submissions with 5 powerful LaTeX snippets.

I've perfected them in 10,000+ hours of coding.

Unlock the secret to lightning-fast paper editing. ↓

I've perfected them in 10,000+ hours of coding.

Unlock the secret to lightning-fast paper editing. ↓

1. Use the right documentclass options before submitting your paper to CHI

How it works:

- Comment out this line of code with % \documentclass[sigconf,authordraft]{acmart}

- Then add \documentclass[manuscript,screen,review, anonymous]{acmart}

This is the right review format.

How it works:

- Comment out this line of code with % \documentclass[sigconf,authordraft]{acmart}

- Then add \documentclass[manuscript,screen,review, anonymous]{acmart}

This is the right review format.

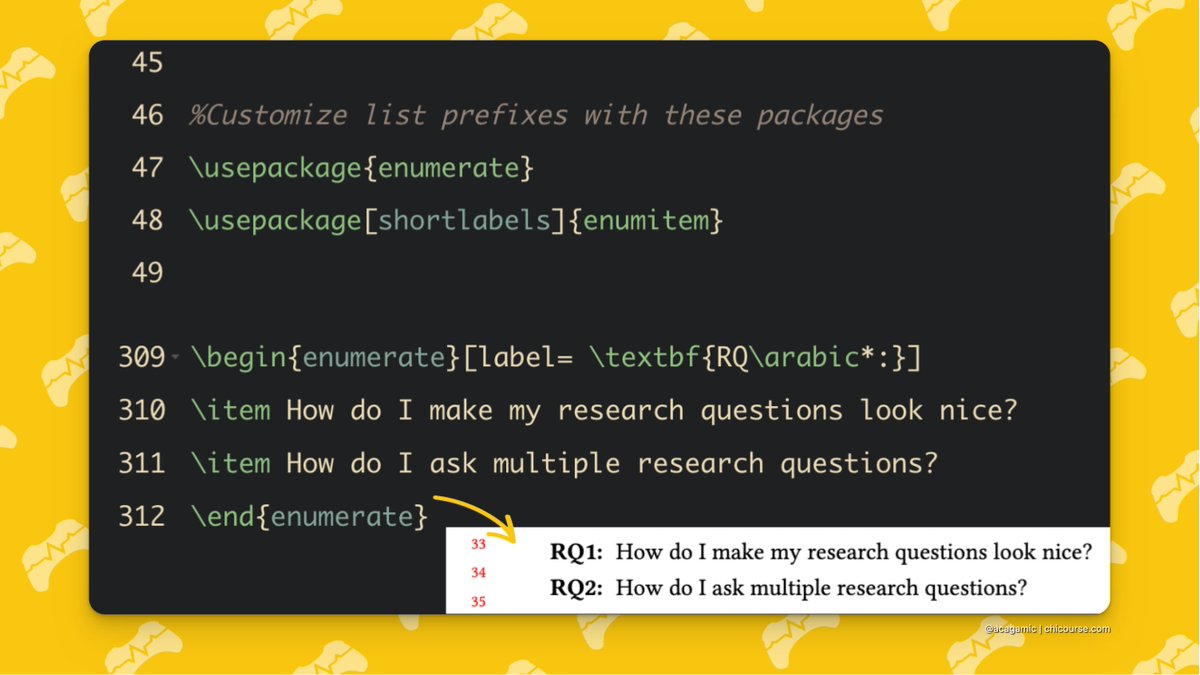

2. Format nicer-looking research questions

How it works:

Load in LaTeX doc header:

\usepackage{enumerate}

\usepackage[shortlabels]{enumitem}

Type in LaTeX doc body:

\begin{enumerate}[label= \textbf{RQ\arabic*:}]

\item x

\end{enumerate}

How it works:

Load in LaTeX doc header:

\usepackage{enumerate}

\usepackage[shortlabels]{enumitem}

Type in LaTeX doc body:

\begin{enumerate}[label= \textbf{RQ\arabic*:}]

\item x

\end{enumerate}

3. Make sure to always define acronyms before use

How it works:

Load in LaTeX doc header:

\usepackage[nolist]{acronym}

Define acronyms:

\begin{acronym}

\acro{ANOVA}{Analysis of Variance}

\end{acronym}

Write the acronym in your text like this:

"We conducted an \ac{ANOVA}."

How it works:

Load in LaTeX doc header:

\usepackage[nolist]{acronym}

Define acronyms:

\begin{acronym}

\acro{ANOVA}{Analysis of Variance}

\end{acronym}

Write the acronym in your text like this:

"We conducted an \ac{ANOVA}."

4. Create pretty quotes for qualitative findings

How it works:

Define a new command called \quoting:

\newcommand{\quoting}[2][P]{``\emph{#2}''\emph{[\textbf{#1}]}}

Use the command like this to quote participants:

\quoting[P13]{This prototype rocked my world.}.

How it works:

Define a new command called \quoting:

\newcommand{\quoting}[2][P]{``\emph{#2}''\emph{[\textbf{#1}]}}

Use the command like this to quote participants:

\quoting[P13]{This prototype rocked my world.}.

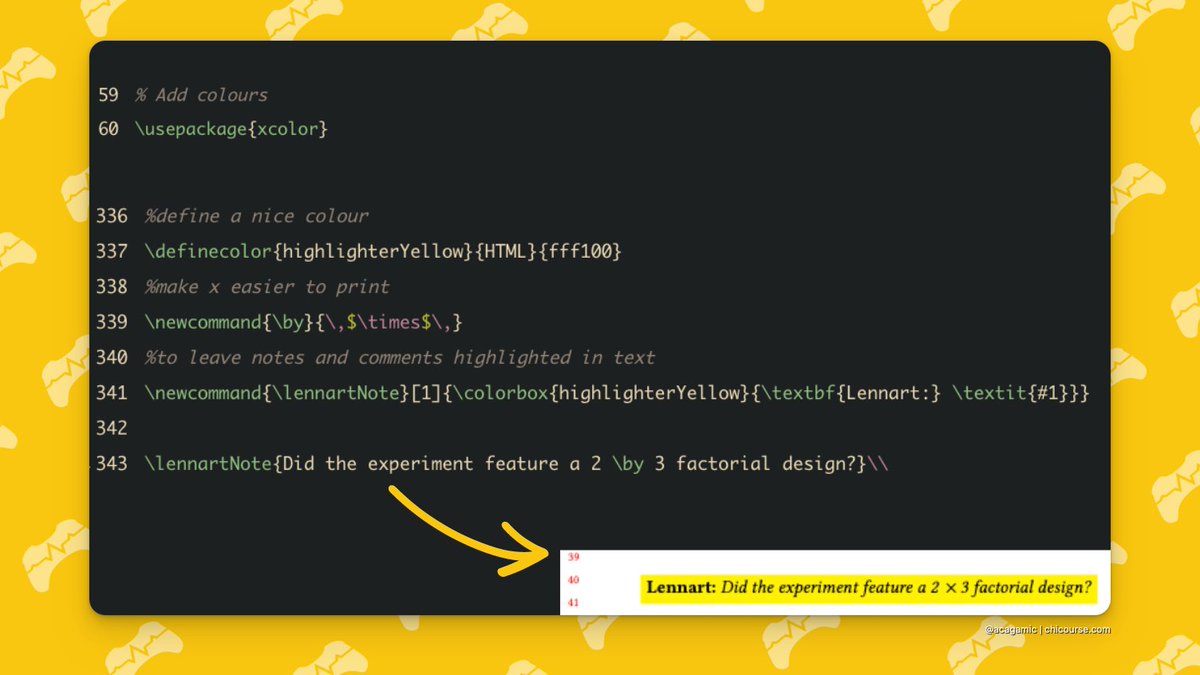

5. Leave highlighted comments

How it works:

Load in LaTeX doc header:

\usepackage{xcolor}

Define:

\definecolor{highlighterYellow}{HTML}{fff100}

\newcommand{\lennartNote}[1]{\colorbox{highlighterYellow}{\textbf{Lennart:} \textit{#1}}}

Use:

\lennartNote{My nice comment}

How it works:

Load in LaTeX doc header:

\usepackage{xcolor}

Define:

\definecolor{highlighterYellow}{HTML}{fff100}

\newcommand{\lennartNote}[1]{\colorbox{highlighterYellow}{\textbf{Lennart:} \textit{#1}}}

Use:

\lennartNote{My nice comment}

TL;DR: 5 drops of my secret LaTeX sauce to write smooth #chi2023 papers

1. Use the right documentclass options for submission

2. Format nicer-looking RQs

3. Always define acronyms before use

4. Create pretty quotes for qualitative findings

5. Leave highlighted comments

1. Use the right documentclass options for submission

2. Format nicer-looking RQs

3. Always define acronyms before use

4. Create pretty quotes for qualitative findings

5. Leave highlighted comments

Done like disco.

If you enjoyed this thread:

1. Follow me @acagamic for more tips on writing research papers

2. Join more than a thousand people on my newsletter (link in profile).

If you enjoyed this thread:

1. Follow me @acagamic for more tips on writing research papers

2. Join more than a thousand people on my newsletter (link in profile).

https://twitter.com/acagamic/status/1643650509905985548

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh