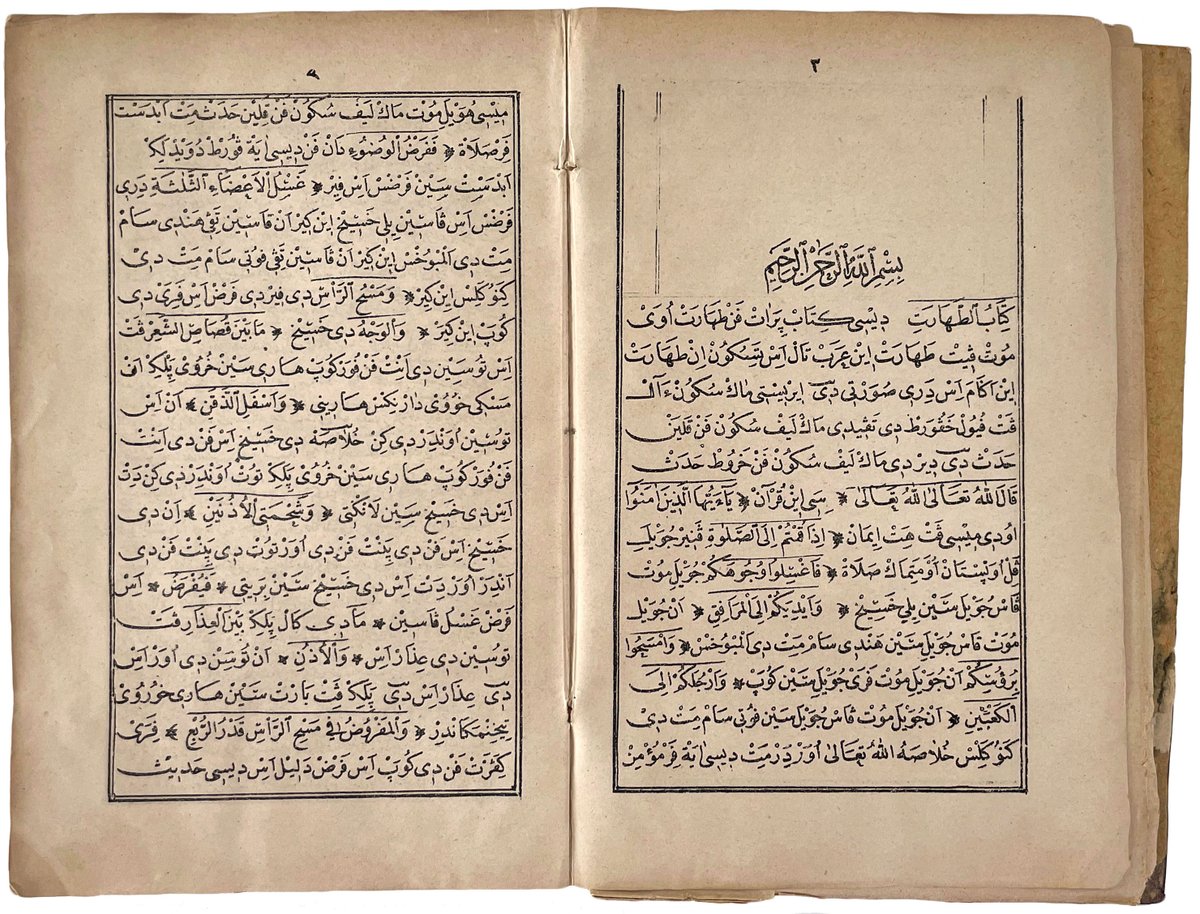

On #YomHashoah: Zvi Kolitz's "Yosl Rakover Speaks to God", set in the last days of the Warsaw Ghetto, a calligraphic manuscript commissioned by a French Jew, with his note on the flyleaf: "To the 26 members of my family who died after deportation 1942-1945". 1/

In "Yosl Rakover", written in Yiddish by Kolitz in 1946 and set In the final days of the Warsaw Ghetto, Rakover, a pious Jew challenges God "And so, my God, before I die, freed from all fear, beyond all terror, [...], I will allow myself to call you to account one last time." 2/

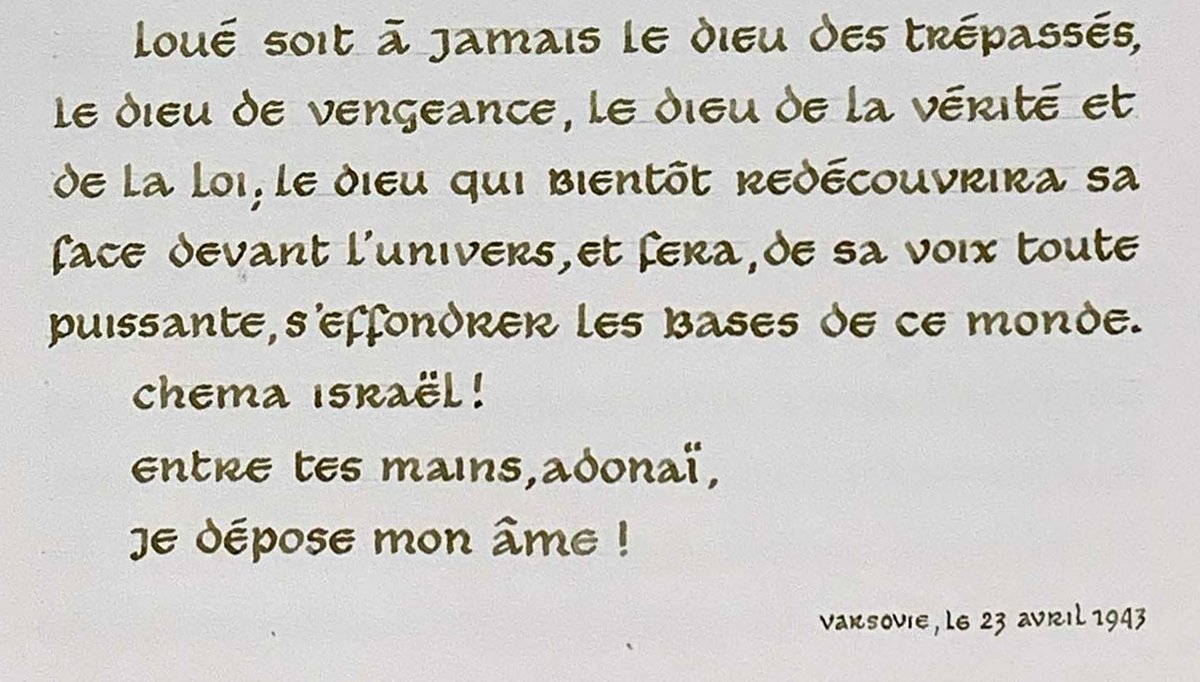

Rakover ends, saying: "I believe in the God of Israel even when he has done everything to make me cease to believe in him" & then, in the seconds before his death: “Sh’ma Yisroel! Hear, Israel! The Lord is our God, the Lord is one. Into Your hands O Lord I commend my soul.” 3/

A second handwritten note describes the emotional impact of the text:

“I have read and re-read these terrible lines of Yossel of Tarnopol often. Every time I cried. I wanted to keep this cry of anguish forever and engrave it on my heart [...].

Dijon, 1965.”

#neverforget 4/

“I have read and re-read these terrible lines of Yossel of Tarnopol often. Every time I cried. I wanted to keep this cry of anguish forever and engrave it on my heart [...].

Dijon, 1965.”

#neverforget 4/

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter