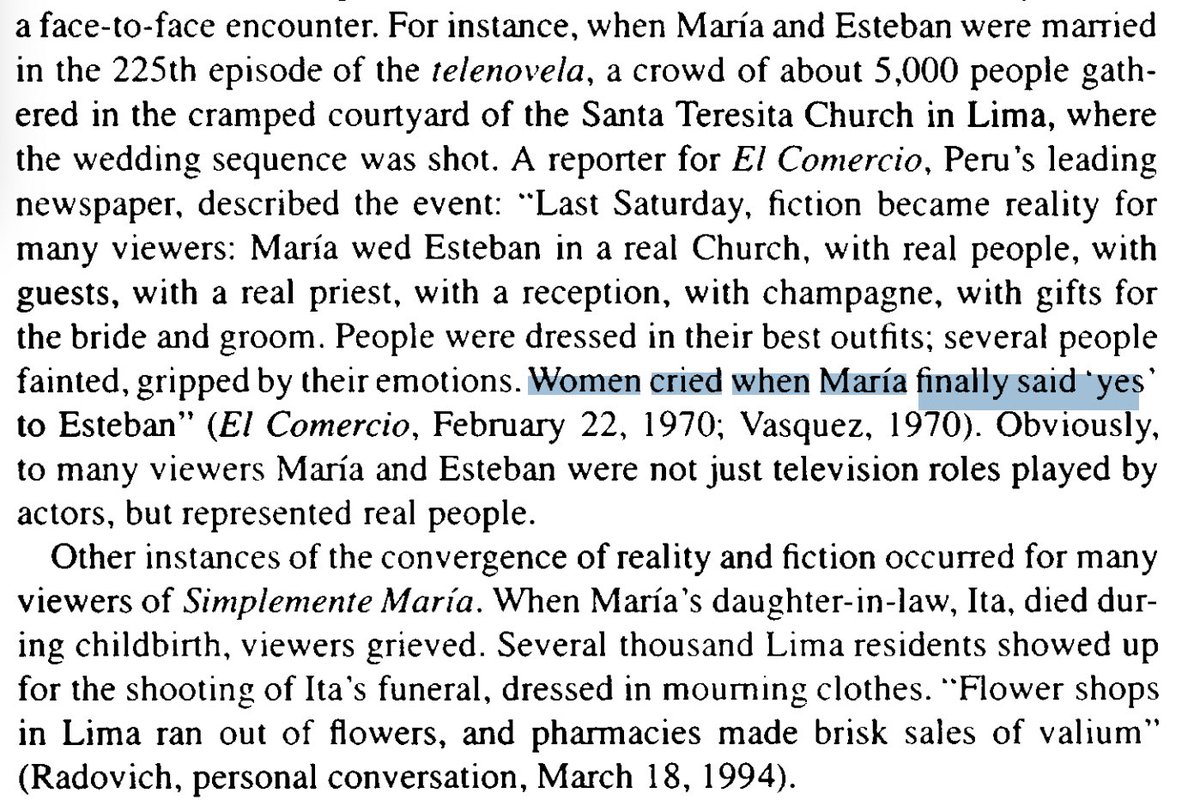

“Simplemente Maria” was an extremely popular telenovela, about a woman who works her way up and eventually marries the father of her child.

When Maria & Esteban married in the 225th episode, 5,000 real people gathered to watch the wedding. Women cried.

THE POWER OF TELEVISION!

When Maria & Esteban married in the 225th episode, 5,000 real people gathered to watch the wedding. Women cried.

THE POWER OF TELEVISION!

It’s hard to work out if TV affects popular attitudes or vice versa.

As a result, quants have shied away from investigating television

And if you read all quant research on cultural change, if you were to read quant research, you’d probably underestimates the impact of TV

As a result, quants have shied away from investigating television

And if you read all quant research on cultural change, if you were to read quant research, you’d probably underestimates the impact of TV

Qualitative social scientists observe huge popular consumption and discussions of television,

But quantitative scholars barely the effect of TV

So I do think that the latter radically underestimate its power.

But quantitative scholars barely the effect of TV

So I do think that the latter radically underestimate its power.

Pritchett would say the same about structural transformation. It’s much easier to calculate the impact of an RCT so randomisation became a popular way to demonstrate causality.

And this surge of publishing led to an inflated sense of its importance, relative to growth.

And this surge of publishing led to an inflated sense of its importance, relative to growth.

In “Simplemente Maria”, the maid learns to sew and then gains upward mobility as a designer in France.

This may have fuelled interest in sewing among house maids in Peru!

The Singer company gave the lead actress a gold sewing machine in gratitude for promoting their machine!

This may have fuelled interest in sewing among house maids in Peru!

The Singer company gave the lead actress a gold sewing machine in gratitude for promoting their machine!

When the lead actress visited the countryside in Peru and other Latin American countries, young women kneeled and kissed the hem of her skirt - akin to idol worship

[just like fans going crazy over Miley Cyrus or Selena Gomez]

[just like fans going crazy over Miley Cyrus or Selena Gomez]

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter